Debate: The Metaverse, flying taxis and other weapons of mass planetary destruction

Fabrice Flipo, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School

5G, 8K, flying taxis and the Metaverse are all topics of great interest, raising many questions. However, such questions are rarely, if ever, from an environmental perspective.

A recent article from French daily newspaper Le Monde, published October 18 2021 and titled “Facebook to hire 10,000 people in Europe to create the Metaverse”, discusses employment, the location of the innovation production site, “use cases” of this application and the experiences it will provide. However, the risks highlighted only relate to addiction or the rights of individuals in the Metaverse.

There is the same narrative framing on the topic of flying taxis, providing promises on the one hand and focusing on the user experience on the other.

In Toulouse, Airbus presents its flying taxi scheduled for 2023 (AFP, 2021).

However, the connection is never made between these initiatives and their potential impact on the biosphere. To find such a connection, you have to go to the “Environment” or “Books” sections of Le Monde: there, consumers are blamed for watching too many videos or sending too many emails.

This means of “compartmentalizing” debates and issues is nothing new – if you flick through old editions of Le Monde, you can find it again and again.

Hype technologies vs punitive environmentalism

Regulation works in the same way. On one side are laws and directives organizing the growth of digital technology and its applications; on the other are those that investigate the environmental implications of such technology, managed by other agencies, such as ADEME (the French Agency for Ecological Transition).

One of the main consequences of this division is making environmentalism appear “punitive”. On the one hand, we have technological innovations and related hype, promising new experiences, fun, happiness and incredible achievements. And on the other, the issue of the environment; discussing waste, energy efficiency, the destruction of the planet and other “depressing”, “boring” issues.

This also holds true for research: researchers with “new, good” technology are placed in the front row, with others left at the back. This is how the mediator at France Info explained that footballer Lionel Messi’s move to Paris Saint-Germain was “worth” more airtime than the report from the IPCC – the first topic was a longer-running story while the IPCC report was a one-off event.

Obliterating a more minimalist approach

Another consequence is that environmental regulation remains largely confined to the area of “energy efficiency”, a technical term referring to the amount of resources and energy needed to manufacture a good or provide a service.

This approach overshadows others, which are essential for the environmental transition – namely, approaches related to using less. Such approaches raise the question of whether we really need a certain good or service. Whether we are talking about 8K or 5G, the not-for-profit Shift Project questions the usefulness of these technologies in light of their forecasted effects on the planet.

The third consequence of this separation between digital expansion and environmental impact is that environmental policy is always struggling to catch up. We see this every day: despite regulation, the digital sector’s environmental impact continues to grow. Technologies are developed for millions or even billions of dollars. And only afterwards does the environmental question get raised. But by then, it is already too late!

Widespread dependencies… that could have been predicted

However, in a large number of cases, the effects of these projects are foreseeable – we can see well in advance which ideas will be disastrous, or at least highly problematic.

Thinking about this early on means we can avoid situations of technological lock-in, such as the widespread dependency on cars or smartphones in our current lifestyles. These are situations that are hard to get out of, as they require coordinating a change in infrastructure and habits, just like the use of bikes in cities “versus” cars.

We can see these easy-to-predict consequences with 5G, 8K, flying taxis and the Metaverse.

For example, 5G is designed to allow for a large increase in data transfer, but comes at a huge energetic cost, even if we have achieved increases in energy efficiency in this area since the 1950s that are just as significant. As emphasized by the Shift Project in their report, though increases in efficiency are stable at the technical level, they cannot compensate for the rise in data…

This reasoning also applies to 8K and the Metaverse, which is basically a conceptually similar, improved version of Second Life, a digital universe launched in 2003 that still exists today. At the time, technology specialist Nicholas Carr remarked that a Second Life avatar consumes about as much energy as the average Brazilian.

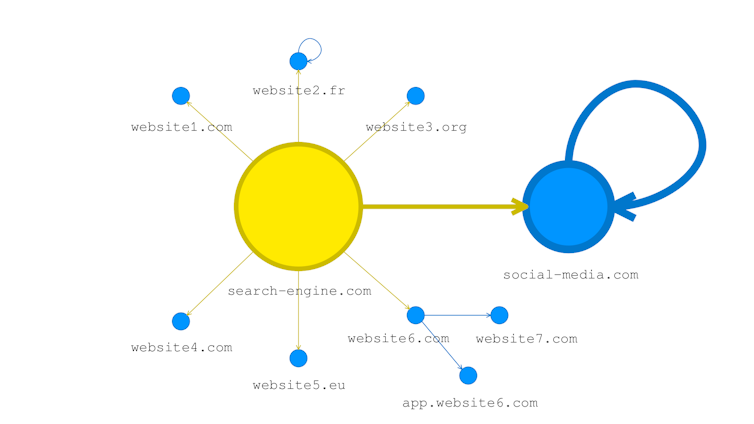

Works of fiction such as Virtual Revolution (2016) depict a world in which the Metaverse will absorb a key part of our social interactions, in the same way that social media is a major vehicle for daily conversations nowadays.

It is easy to predict the amount of information that will need to be produced and processed, compared with what exists already. IT company Cisco warns that these universes could easily become the biggest source of traffic on the internet.

As for flying taxis, their aim is to find space in the air that has been “lost” on the ground: in short, to clog up one of the last remaining spaces, despite the fact that moving up and down generally uses more energy than moving horizontally, due to gravity.

Our relationship to nature

We can see that it is not hard to establish the connection between technological innovation and the environmental situation, there is no conceptual difficulty here. And environmentalism does not always have to be lagging behind.

Back in Marx’s time, he explained that the question of humans’ relationship to nature is technical and so are our choices. It goes far beyond taking a blissful weekend stroll and admiring supposedly untouched areas…

Environmentalists have long been arguing that certain technological choices are incompatible with conditions for a good life on Earth. But these problems are formulated in the public sphere in a compartmentalized way, which prevents any serious discussion.

So what is the blockage?

Environmentalism does not have to be a “punitive” issue. Bike-riding, local products, renewable energy, insulation, DIY, and more… There are many environmental initiatives that can be discussed in the public sphere, as long as the various possible avenues are appropriately addressed.

So where is the issue? Why does hype benefit so many projects, when we can easily show that they will post huge problems once deployed on a certain scale? There are several explanations.

Tech projects receive the most funding, and are capable of a huge amount of impact in terms of persuasive power. They make use of marketing, surveys and other tools, perfectly dosing and precisely targeting their storytelling to reach the most receptive audiences, before progressively expanding to new fringes of the population, until they achieve saturation.

These selectively edited stories are also a part of the broader history of developed societies and their journey to create the most capital-intensive technologies, as Marx showed as early as 1867, emphasizing the effects of expanded reproduction of capital. Socialism also placed plenty of hope in this “expansion of productive forces”.

Moving away from this linear history, always pursuing the same aim, is seen as “moving backwards” and somehow, we would prefer to continue this narrative than preserve life on Earth. A narrative where science and science fiction combine, like Elon Musk announcing a future colony on Mars. Here, cognitive bias, known as the “Othello effect”, is at play.

Another explanation relates to capitalization itself, which represents a means of power for organizations. The greater the capitalization, the more the networks controlled by the organization will grow – and the greater the persuasive power. Elon Musk (yes, him again) aims to control the entire fleet of personal vehicles, with his robotaxis and self-driving cars. And what is true of companies is also true of governments, as highlighted by François Fourquet in his work “Les Comptes de la puissance” (The Accounts of Power).

While dominant ideas of socialism in the 20th century have always been fascinated by the collective power created by capitalism, trying to make it benefit as many as possible, environmentalism, on the other hand, supports decentralized initiatives and short circuits.

This trend often breaks with the “politics of power”, which explains in particular why conservatives are so opposed to it. Is it “realistic”, in a world where countries try to dominate each other? But on the other hand, can the leadership race last indefinitely if it undermines life on Earth?

Fabrice Flipo, Professor of social and political philosophy, epistemology and history of science and technology at Institut Mines-Télécom Business School

This article was republished from The Conversation under the Creative Commons license. Read the original article here (in French).