Sovereignty and digital technology: controlling our own destiny

Annie Blandin-Obernesser, IMT Atlantique – Institut Mines-Télécom

Facebook has an Oversight Board, a kind of “Supreme Court” that rules on content moderation disputes. Digital giants like Google are investing in the submarine telecommunications cable market. France has had to back pedal after choosing Microsoft to host the Health Data Hub.

These are just a few examples demonstrating that the way in which digital technology is developing poses a threat not only to the European Union and France’s economic independence and cultural identity. Sovereignty itself is being questioned, threatened by the digital world, but also finding its own form of expression there.

What is most striking is that major non-European digital platforms are appropriating aspects of sovereignty: a transnational territory, i.e. their market and site where they pronounce norms, a population of internet users, a language, virtual currencies, optimized taxation, and the power to issue rules and regulations. The aspect that is unique to the digital context is based on the production and use of data and control over information access. This represents a form of competition with countries or the EU.

Sovereignty in all its forms being questioned

The concept of digital sovereignty has matured since it was formalized around ten years ago as an objective to “control our own destinies online”. The current context is different to when it emerged. Now, it is sovereignty in general that is seeing a resurgence of interest, or even souverainism (an approach that prioritizes protecting sovereignty).

This topic has never been so politicized. Public debate is structured around themes such as state sovereignty regarding the EU and EU law, economic independence, or even strategic autonomy with regards to the world, citizenship and democracy.

In reality, digital sovereignty is built on the basis of digital regulation, controlling its material elements and creating a democratic space. It is necessary to take real action, or else risk seeing digital sovereignty fall hostage to overly theoretical debates. This means there are many initiatives that claim to be an integral part of sovereignty.

Regulation serving digital sovereignty

The legal framework of the online world is based on values that shape Europe’s path, specifically, protecting personal data and privacy, and promoting general interest, for example in data governance.

The text that best represents the European approach is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), adopted in 2016, which aims to allow citizens to control their own data, similar to a form of individual sovereignty. This regulation is often presented as a success and a model to be followed, even if it has to be put in perspective.

New European digital legislation for 2022

The current situation is marked by proposed new digital legislation with two regulations, to be adopted in 2022.

It aims to regulate platforms that connect service providers and users or offer services to rank or optimize content, goods or services offered or uploaded online by third parties: Google, Meta (Facebook), Apple, Amazon, and many others besides.

The question of sovereignty is also present in this reform, as shown by the debate around the need to focus on GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft).

On the one hand, the Digital Markets Act (the forthcoming European legislation) includes strengthened obligations for “gatekeeper” platforms, which intermediate and end-users rely on. This affects GAFAM, even if it may be other companies that are concerned – like Booking.com or Airbnb. It all depends on what comes out of the current discussions.

And on the other hand, the Digital Services Act is a regulation for digital services that will structure the responsibility of platforms, specifically in terms of the illegal content that they may contain.

Online space, site of confrontation

Having legal regulations is not enough.

“The United States have GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple), China has BATX (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Xiaomi). And in Europe, we have the GDPR. It is time to no longer depend solely on American or Chinese solutions!” declared French President Emmanuel Macron during an interview on December 8 2020.

Interview between Emmanuel Macron and Niklas Zennström (CEO of Atomico). Source: Atomico on Medium.

The international space is a site of confrontation between different kinds of sovereignty. Every individual wants to truly control their own digital destiny, but we have to reckon with the ambition of countries that demand the general right to control or monitor their online space, such as the United States or China.

The EU and/or its member states, such as France, must therefore take action and promote sovereign solutions, or else risk becoming a “digital colony”.

Controlling infrastructure and strategic resources

With all the focus on intermediary services, there is not enough emphasis placed on the industrial dimension of this topic.

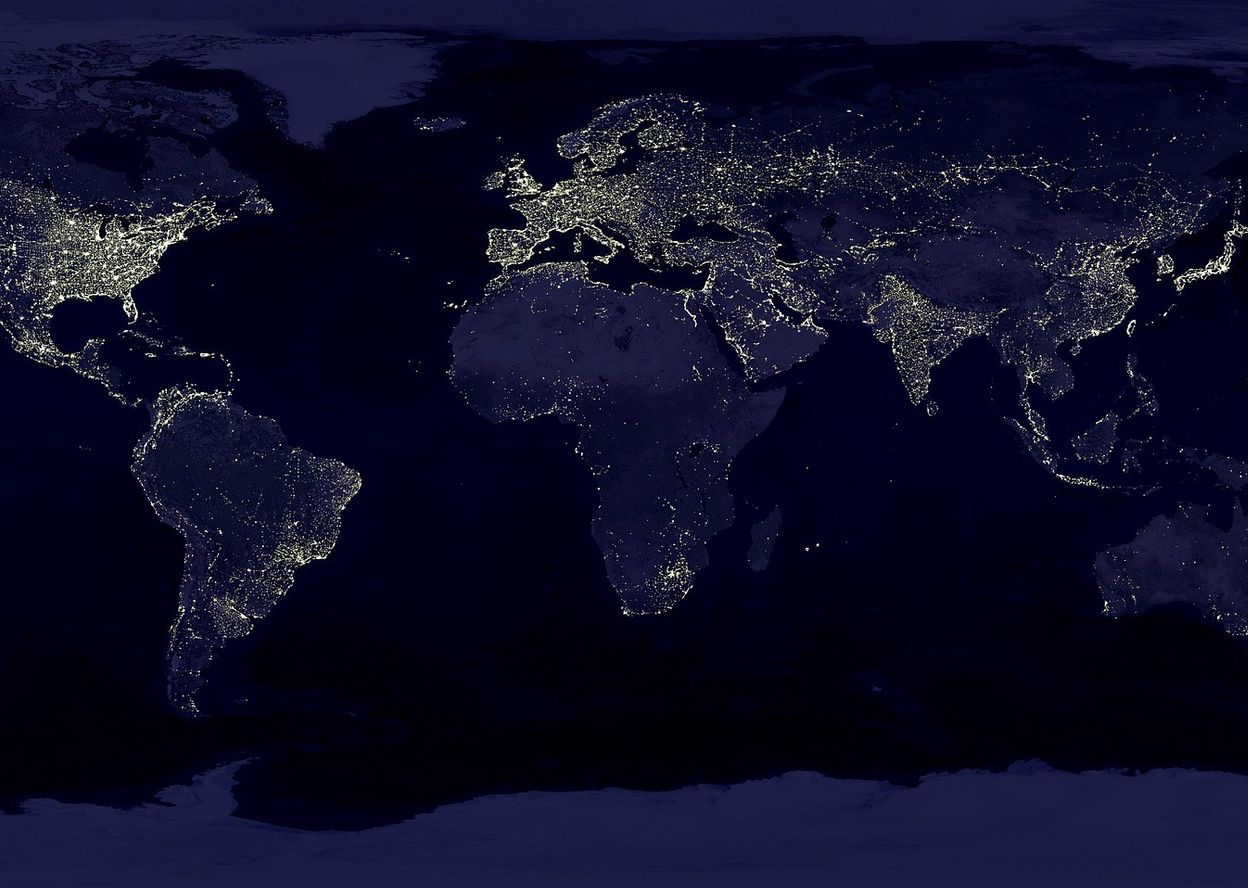

And yet, the most important challenge resides in controlling vital infrastructure and telecommunications networks. The question of submarine cables, used to transfer 98% of the world’s digital data, receives far less media attention than the issue of 5G devices and Huawei’s resistance. However, it demonstrates the need to promote our cable industry in the face of the hegemony of foreign companies and the arrival of giants such as Google or Facebook in the sector.

The adjective “sovereign” is also applied to other strategic resources. For example, the EU wants to secure its supply of semi-conductors, as currently, it depends on Asia significantly. This is the purpose of the European Chips Act, which aims to create a European ecosystem for these materials. For Ursula von der Leyen, “it is not only a question of competitiveness, but also of digital sovereignty.”

There is also the question of a “sovereign” cloud, which has been difficult to implement. There are many conditions required to establish sovereignty, including the territorialization of the cloud, trust and data protection. But with this objective in mind, France has created the label SecNumCloud and announced substantial funding.

Additionally, the adjective “sovereign” is used to describe certain kinds of data, for which states should not depend on anyone for their access, such as geographic data. In a general way, a consensus has been reached around the need to control data and access to information, particularly in areas where the challenge of sovereignty is greatest, such as health, agriculture, food and the environment. Development of artificial intelligence is closely connected to the status of this data.

Time for alternatives

Does all that mean facilitating the emergence of major European or national actors and/or strategic actors, start-ups and SMEs? Certainly, such actors will still need to show good intentions, compared to those that shamelessly exploit personal data, for example.

A pure alternative is difficult to bring about. This is why partnerships develop, although they are still highly criticized, to offer cloud hosting for example, like the collaboration between Thales and OVHcloud in October 2021.

On the other hand, there is reason to hope. Open-source software is a good example of a credible alternative to American private technology firms. It needs to be better promoted, particularly in France.

Lastly, cybersecurity and cyberdefense are critical issues for sovereignty. The situation is critical, with attacks coming from Russia and China in particular. Cybersecurity is one of the major sectors in which France is greatly investing at present and positioning itself as a leader.

Sovereignty of the people

To conclude, it should be noted that challenges relating to digital sovereignty are present in all human activities. One of the major revelations occurred in 2005, in the area of culture, when Jean-Noël Jeanneney observed that Google had defied Europe by creating Google Books and digitizing the continent’s cultural heritage.

The recent period reconnects with this vision, with cultural and democratic issues clearly essential in this time of online misinformation and its multitude of negative consequences, particularly for elections. This means placing citizens at the center of mechanisms and democratizing the digital world, by freeing individuals from the clutches of internet giants, whose control is not limited to economics and sovereignty. The fabric of major platforms is woven from the human cognitive system, attention and freedom. Which means that, in this case, the sovereignty of the people is synonymous with resistance.

Annie Blandin-Obernesser, Law professor, IMT Atlantique – Institut Mines-Télécom

This article was republished from The Conversation under the Creative Commons license. Read the original article here (in French).