New Caledonia: a mine challenging democracy

When an industrial mining complex wanted to release a pollutant into their lagoon in the late 1990s, the inhabitants of the southern province of Grande Terre took action. In their fight against the environmental and cultural danger, the citizens found it difficult to make their voices heard. Today, almost 20 years have passed since the scientific and social controversy first shook this region. Work in the area of sociology, carried out by Julien Merlin from Mines ParisTech and Mines Nancy reveals how these inhabitants succeeded in changing the game, and making their political voice heard over time.

It is June 8, 2006. Angry voices fill the streets in Nouméa. This anger has mobilized the 2,500 people gathered together by the indigenous committee of Rhéébu Nùù—a citizen collective advocating for Kanak interests. On this day, demonstrators once again took to the streets to demand an end to the landscaping projects underway on the Goro plateau, on the southern tip of the main island, and the construction of the associated mine site. Yet, historically, New Caledonia had not been opposed to mining. Mining activity had been going on in the territory for over a century. Nouméa was even home to a nickel mine operated by Société Le Nickel (SLN), which was founded on the island in 1880 to tap into this local mineral resource.

But the project on the Goro plateau was different. The mining activity was operated by another company from Canada: Inco. When the company decided to establish a mine here in 1999, it proposed an innovative project, which broke with the extraction and upgrading methods the other New Caledonian mining complexes had been using. Inco was interested in the nickel found in laterites, a different rock type than the garnierite sought after by its competitors. However, a different type of process is used to extract the nickel from the laterites. The hydrometallurgical process that is required leads to the release of a chemical element, manganese, that Inco planned to discharge into the New Caledonian lagoon. But the inhabitants living near the Goro plateau said “no”. This was the start of a long social and scientific debate that remains emblematic of citizen mobilization that can succeed in creating new values.

As a sociologist specializing in controversies with Mines Nancy and Mines ParisTech, Julien Merlin is particularly interested in social conflicts related to mining operations. The “Goro-nickel” project initiated by Inco is his favorite topic—and the focus of the thesis he will complete next fall. He presented part of this thesis at a scientific seminar organized by the Mine & Société Network of Excellence on May 16, 2017 at Mines ParisTech. By analyzing disputes between citizens, administrations and companies, he studies how new demands arise and how stakeholders structure their action. In the background, what is unfolding is a new way of organizing democratic life on a local level. How do these controversies lead to the creation of an identity citizens connect with? What connections are created between civil society actors in order to promote citizen expertise, and how is this expertise recognized?

The young researcher sees the Goro-nickel as emblematic of these issues. When the first voices were heard speaking out against the project in 2002, they were dissonant. On the one hand, the Kanak tribes made economic demands. “The indigenous community demanded that the entire subcontracting sector related to the factory, such as earthmoving operations and staff catering facilities, be assigned to local Kanak companies,” Julien Merlin explains. On the other hand, environmental organizations, like Corail Vivant, fought for the preservation of the New Caledonian lagoon, so that it could become a UNESCO world heritage site. And a pipe dumping manganese into the ocean represented a serious obstacle in obtaining this designation.

Strength in Unity

It’s hard to imagine any motive that would bring these two different arguments together. However, over the next two or three years, the environmental organizations forged relationships that did not previously exist with Kanak tribes to create a common cause. “We have to understand that behind the indigenous peoples’ economic motivations was an assertion of their identity,” the sociologist explains. “What they were seeking, above all, was a recognition of their link to the land, within the context of an economic imbalance between the Kanak population and the population descended from colonial settlers.”

Little by little, the two movements began to harmonize. The two groups came together under one banner set to kill two birds with one stone. The assertion of identity and the economic demands now became the movement in defense of cultural and natural heritage. The local Rhéébu Nùù collective drew on international legal tools, defined by the UN, in defense of traditional indigenous intellectual property. For example, based on an article of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, the Kanak citizens asserted the right to monitor the land development of their territory based on their status as an indigenous population. They saw the New Caledonian environment as an integral part of their culture and history: they must have decision-making power in these issues.

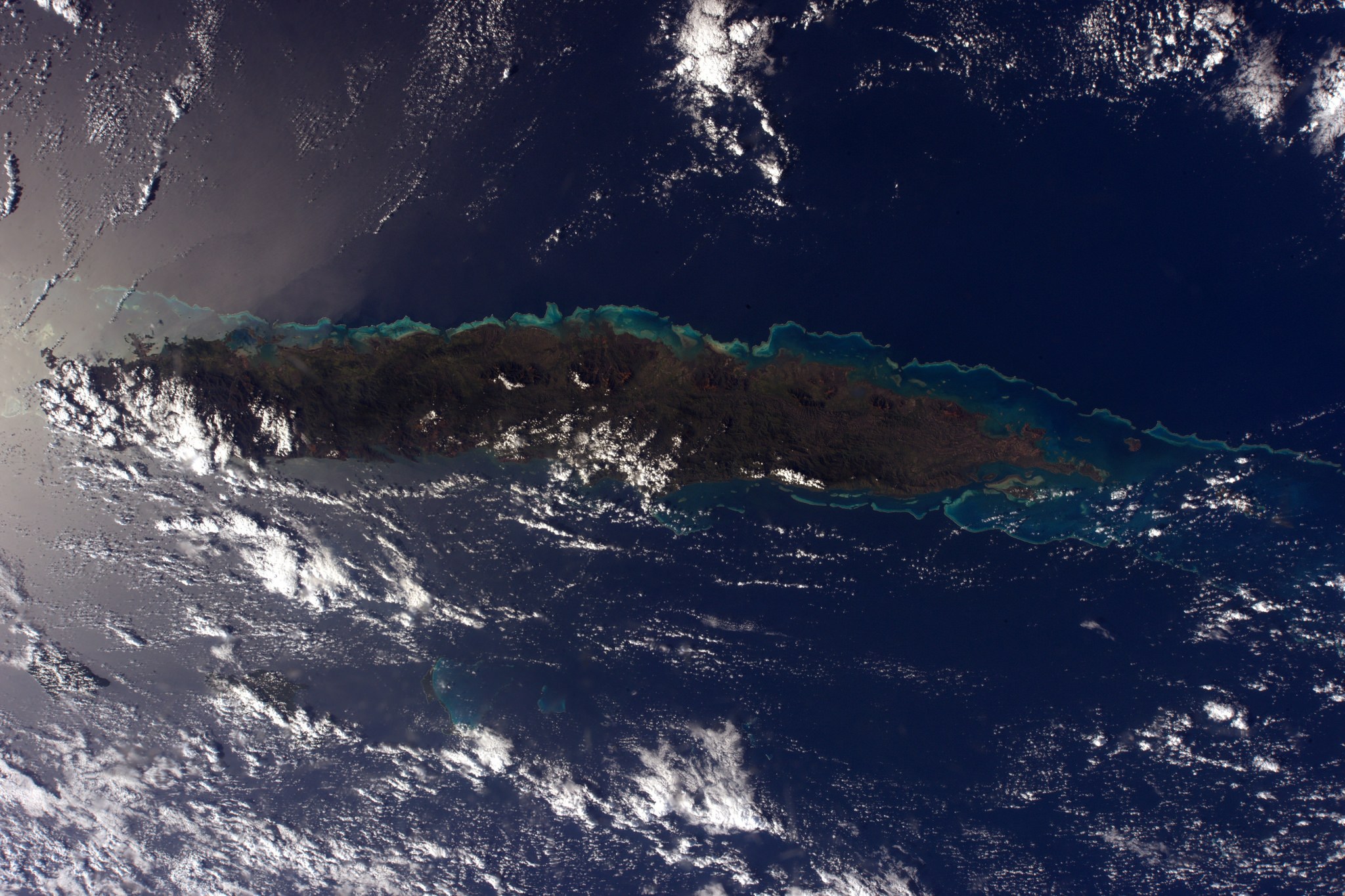

Protection of the New Caledonian lagoon became a common cause that united the actors speaking out against the Goro-Nickel project. Photo: Thomas Pesquet.

“The actors coming together in this way, as the direct result of Goro-nickel project controversy, created new values and new identity,” Julien Merlin points out. “Before these two groups formed a common cause, the discourse related to indigenous identity in New Caledonia was primarily nationalistic.” The Goro-nickel controversy therefore caused a new type of discourse on identity, based on heritage and the connection to nature. Locally, the Rhéébu Nùù collective’s influence was so great that in the Yaté municipality, near the Goro plateau, mayor Étienne Ouetcho was elected on the collective’s ticket and held office from 2008 to 2014. It was the first time since 1977 that the FLNKS independentist party was replaced in the city’s administration—before again winning the municipal elections in 2014. This change can also apparent regarding environmental issues. Whereas before these issues received little attention, they are now key components in New Caledonia’s political debates. “At the same time as this new indigenous identity was emerging, a new identity was also created for the land, as an environment that must be protected,” the researcher explains.

Citizen expertise

The reason this new discourse on environmental issues and identity has resulted in such a strong local response, is that it was able to gain legitimacy, putting the Goro-nickel project on hold for several years. Throughout the entire first phase of the controversy, the organizations forming a common cause were not being heard due to the absence of an established institutional mechanism that could increase their impact. In addition, their inability to provide any expertise to counter the project engineers and scientists was systematically emphasized.

So how did the citizens succeed in changing this situation? “In response to the refusal to hear their arguments, the organizations and local population went to the industrial site to destroy equipment, stop the construction work, and prevent the work site from continuing any further,” explains Julien Merlin. When they found it impossible to make their voices heard, the citizens chose “a situation of extreme violence,” the researcher explains. To handle this situation, the local authorities decided to create an information, consultation and oversight committee (CICS) to assess the environmental impacts of the Goro site. The committee brought together representatives from the government, Inco company, and the Rhéébu Nùù collective. Each with their analyses and specialists.

With the establishment of this consultation committee to examine the assessments and counter-assessments, the manganese problem could be introduced into the discussions. The technical demands were also heard. Problems such as the amount of manganese released into the lagoon, were therefore brought to the forefront. The company had planned to release 100 milligrams per liter of water into the ocean, whereas legislation in mainland France only authorized amounts 100 times less than this. The organizations were also able to present its case using local expertise on the lagoon’s current patterns, demonstrating an accumulation of manganese that would be higher in this context than in the context of coastal regions in mainland France.

[padding right=”10%” left=”30%”]« In the Goro-nickel project case, the citizens perfectly demonstrated their ability to understand the social and technical issues. »[/padding]

“In this case, the technical issue truly brought forth an issue of democracy at the micro-local level: how can small-scale citizen demands be taken into account?” Julien Merlin observes. And it built on a criticism often made concerning citizens involved in this type of struggle: “This mobilization is clearly deeper than an instinctive refusal based solely on factory’s geographical proximity.” The “not in my backyard” syndrome, or Nimby, as some scientists refer to it, is too limited to encompass the deep motivations of the indigenous community and environmentalists. “This approach views citizen action almost as pathological: people take action because they do not understand the problems. But in the Goro-nickel project case, the citizens perfectly demonstrated their ability to understand the social and technical issues.”

The lessons from Goro-nickel

Has the New Caledonian case changed consultation processes on a larger scale, by influencing other regional planning projects? It’s a tricky question. First because the New Caledonian administration is independent, making the transfer of political practices complex. Secondly, the social and cultural issues differ depending on the context. The mineral drilling project at the Merléac site in Brittany recently made the news after coming to a halt due to citizen mobilization and government announcements. Julien Merlin—who is also studying this case—emphasizes that the Merléac project, for example, does not have the same implications in terms of identity issues as those involved in the Goro-Nickel project. The consultation mechanisms that work well in one situation are not necessarily effective in another situation.

However, a few initiatives have shown that the French administration is trying to take this new mobilization dimension into account at the national level. One such initiative, launched in April 2015 by Emmanuel Macron when he was France’s Minister of Economy, Industry and Digital Affairs, is worth mentioning. In his role in charge of the mining projects associated with his ministry, he launched the initiative entitled “Responsible Mining” (“Mine responsable”) to ensure that these sites met the requirements of the new national sustainable development strategy. Yet the consultation aimed at bringing the stakeholders together did not prove successful. “The environmental organizations chose to withdraw from the process,” the young sociologist recalls. “They were not satisfied with the format of the consultation. This shows that the real problem is linked to the representation issue: how can organizations, experts, and industrial players all be fairly represented?” The administration appears to be seeking answers to this question. For example, in late May, Nicolas Hulot, the new Minister of Ecological and Solidarity Transition, announced that he wanted to commission an independent study of the Merléac drilling project.

Hidden behind this issue are questions of democracy and legislation, regardless of where the controversy takes place. By using technical, identity and economic arguments, the organizations openly question what the projects’ impacts will be. They question what the economic consequences will be at the local level, and call into question the general interest of resuming mining operations in France. Furthermore, their objections often highlight the outdated Mining Code. Few changes have been made to this code over the past few decades, and those changes were primarily related to post-mining: management of the former mining sites, upgrading the facilities… The organizations contest the mining timetable that pushes projects through before a comprehensive reform of the code, which must be brought into line with the Environmental Code.

What does the future hold for Goro?

Now back to Yaté and the Goro plateau, where do things stand today? In 2006, the Brazilian company Vale acquired the Inco project, and continued the consultation process with the various stakeholders, including the citizen associations. The environmentalists and indigenous organizations no longer form a common cause, but primarily for procedural reasons: each group is represented within the consultation associations. In order to limit the release of manganese in the lagoon, Vale chose not to complete the hydrometallurgical process on site. The company therefore complies with legislation of mainland France by only releasing a quantity that is less than the threshold amount of 1 milligram per liter of water. To accomplish this, the company had to develop a new method for the processing change. The residents’ social action has therefore been become a part of the project’s technical aspect.

The operation was therefore able to begin, although protests persisted, despite 6 marine sites becoming UNESCO world heritage sites in 2008. That year, Vale suffered several mishaps, including a major acid leak in the lagoon at the southern tip of the island, a little over two years ago. The citizens and organizations are therefore continuing their fight to increase industrial safety and better protect the environment. At this point, the actors have already structured their action, and it appears things are running more smoothly than they were fifteen years ago, when the mobilization was still in its infancy. The citizen expertise has been institutionalized. The CICS still exists, and a Grand Sud environmental quality monitoring system has been created: l’Œil. Created directly following the Goro-Nickel controversy, the goal is to expand this initiative to include the entire southern province. Yet this could create new controversies. Would it be legitimate for the local Goro collective to represent the entire territory? Should new collectives be integrated in the process? One thing is for sure, the sociologists will closely study these developments.

[box type=”info” align=”” class=”” width=””]

2 questions for Julien Merlin, controversy sociologist

Julien Merlin is conducting his thesis work on New Caledonia, funded by a doctoral contract at the Centre for Innovation Sociology at Mines ParisTech. He is also conducting post-doctorate work on the resurgence of mining activity in mainland France, funded by Labex Ressources 21 and the Grand Est region, at Mines Nancy and the University of Lorraine. In two questions, he explains the significance of his research.

Why study scientific controversies?

Julien Merlin: What’s interesting is to study the “productive” aspect of controversies. They lead to the formulation of new social identities, to the production of new expertise and knowledge, and reveal the political nature of science and technology. Therefore, the goal is not to study everything related to science and technology on the one hand, and sociological issues on the other. On the contrary, the goal is to study how these aspects are produced together.

What does the Goro-Nickel controversy contribute to sociology?

JM: Goro-Nickel is an exemplary case. An issue that could be reduced to a technical problem —the environmental impact of a pipe dumping manganese— or a social problem —the Kanak identity— exists in a co-definition dynamic. It is interesting to note that this feature is now ubiquitous, and extends far beyond mining projects. Not too long ago, it was not easy to say that science and technology raised questions of democracy. The study of controversies sheds light on this aspect. In the future, the role that science and technology should play within companies will certainly be discussed by civil society actors to a greater extent.[/box]