Encrypting and watermarking health data to protect it

As medicine and genetics make increasing use of data science and AI, the question of how to protect this sensitive information is becoming increasingly important to all those involved in health. A team from the LaTIM laboratory is working on these issues, with solutions such as encryption and watermarking. It has just been accredited by Inserm.

The original version of this article has been published on the website of IMT Atlantique

Securing medical data

Securing medical data, preventing it from being misused for commercial or malicious purposes, from being distorted or even destroyed has become a major challenge for both health players and public authorities. This is particularly relevant at a time when progress in medicine (and genetics) is increasingly based on the use of huge quantities of data, particularly with the rise of artificial intelligence. Several recent incidents (cyber-attacks, data leaks, etc.) have highlighted the urgent need to act against this type of risk. The issue also concerns each and every one of us: no one wants their medical information to be accessible to everyone.

“Health data, which is particularly sensitive, can be sold at a higher price than bank data,” points out Gouenou Coatrieux, a teacher-researcher at LaTIM (the Medical Information Processing Laboratory, shared by IMT Atlantique, the University of Western Brittany (UBO) and Inserm), who is working on this subject in conjunction with Brest University Hospital. To enable this data to be shared while also limiting the risks, LaTIM are usnig two techniques: secure computing and watermarking.

Secure computing, which combines a set of cryptographic techniques for distributed computing along with other approaches, ensures confidentiality: the externalized data is coded in such a way that it is possible to continue to perform calculations on it. The research organisation that receives the data – be it a public laboratory or private company – can study it, but doesn’t have access to its initial version, which it cannot reconstruct. They therefore remain protected.

Gouenou Coatrieux, teacher-researcher at LaTIM

(Laboratoire de traitement de l’information médicale, common to IMT Atlantique, Université de Bretagne occidentale (UBO) and Inserm

Discreet but effective tattooing

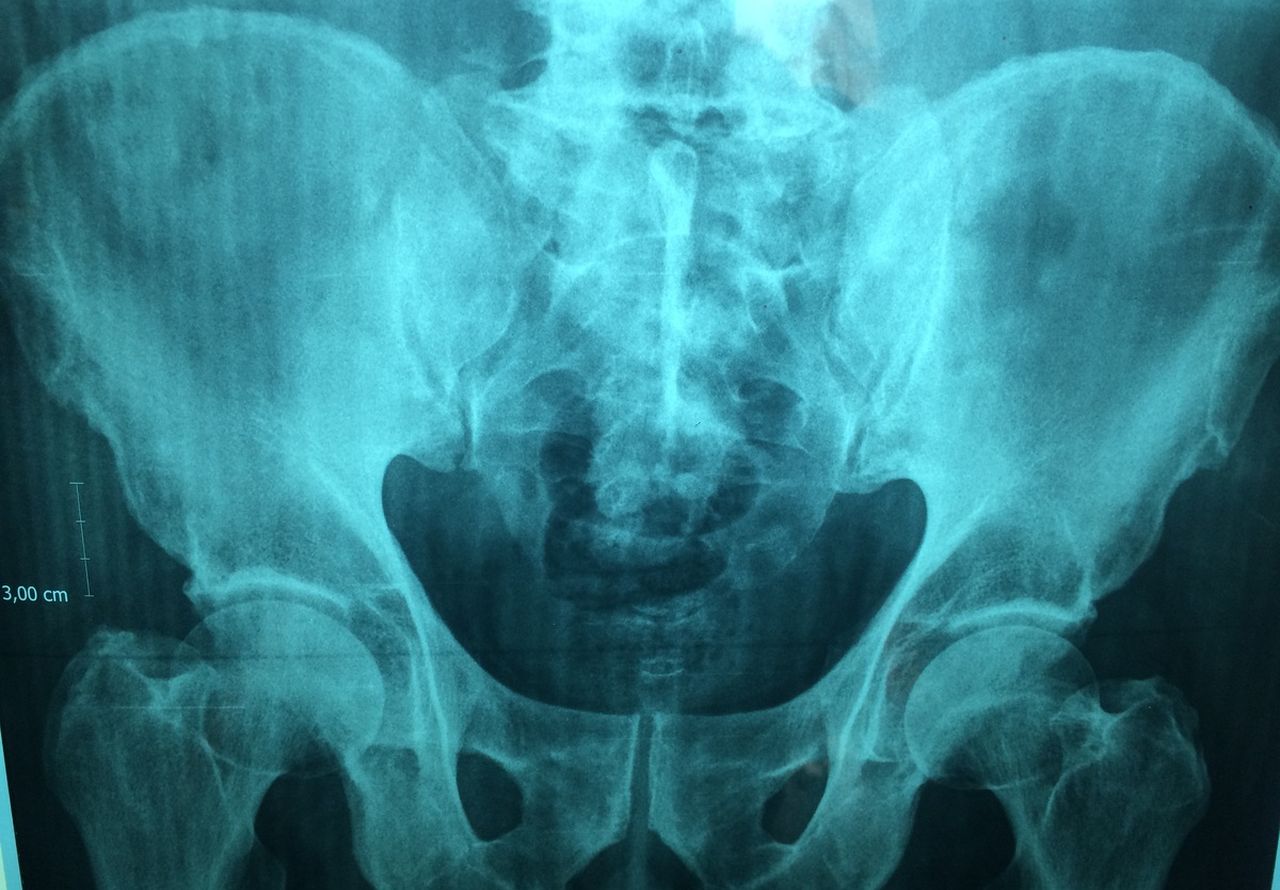

Tattooing involves introducing a minor and imperceptible modification into medical images or data entrusted to a third party. “We simply modify a few pixels on an image, for example to change the colour a little, a subtle change that makes it possible to code a message,” explains Gouenou Coatrieux. We can thus tattoo the identifier of the last person to access the data. This method does not prevent the file from being used, but if a problem occurs, it makes it very easy to identify the person who leaked it. The tattoo thus guarantees traceability. It also creates a form of dissuasion, because users are informed of this device. This technique has long been used to combat digital video piracy. Encryption and tattooing can also be combined: this is called crypto-tattooing.

Initially, LaTIM team was interested in the protection of medical images. A joint laboratory was thus created with Medecom, a Breton company specialising in this field, which produces software dedicated to radiology.

Multiple fields of application

Subsequently, LaTIM extended its field of research to the entire field of cyber-health. This work has led to the filing of several patents. A former doctoral student and engineer from the school has also founded a company, WaToo, specialising in data tagging. A Cyber Health team at LaTIM, the first in this field, has just been accredited by Inserm. This multidisciplinary team includes researchers, research engineers, doctoral students and post-docs, and includes several fields of application: protection of medical images and genetic data, and ‘big data’ in health. In particular, it works on the databases used for AI and deep learning, and on the security of treatments that use AI. “For all these subjects, we need to be in constant contact with health and genetics specialists,” stresses Gouenou Coatrieux, head of the new entity. We also take into account standards in the field such as DICOM, the international standard for medical imaging, and legal issues such as those relating to privacy rights with the application of European RGPD regulations.

The Cyber Health team recently contributed to a project called PrivGen, selected by the Labex (laboratory of excellence) CominLabs. The ongoing work which started with PrivGen aims to identify markers of certain diseases in a secure manner, by comparing the genomes of patients with those of healthy people, and to analyse some of the patients’ genomes. But the volumes of data and the computing power required to analyse them are so large that they have to be shared and taken out of their original information systems and sent to supercomputers. “This data sharing creates an additional risk of leakage or disclosure,” warns the researcher. “PrivGen’s partners are currently working to find a technical solution to secure the treatments, in particular to prevent patient identification”.

Towards the launch of a chaire (French research consortium)

An industrial chaire called Cybaile, dedicated to cybersecurity for trusted artificial intelligence in health, will also be launched next fall. LaTIM will partner with three other organizations: Thales group, Sophia Genetics and the start-up Aiintense, a specialist in neuroscience data. With the support of Inserm, and with the backing of the Regional Council of Brittany, it will focus in particular on securing the learning of AI models in health, in order to help with decision-making – screening, diagnoses, and treatment advice. “If we have a large amount of data, and therefore representations of the disease, we can use AI to detect signs of anomalies and set up decision support systems,” says Gouenou Coatrieux. “In ophthalmology, for example, we rely on a large quantity of images of the back of the eye to identify or detect pathologies and treat them better.“