3D printing, a revolution for the construction industry?

Estelle Hynek, IMT Nord Europe – Institut Mines-Télécom

A two-story office building was “printed” in Dubai in 2019, becoming the largest 3D-printed building in the world by surface area: 640 square meters. In France, XtreeE plans to build five homes for rent by the end of 2021 as part of the Viliaprint project. Constructions 3D, with whom I am collaborating for my thesis, printed the walls of the pavilion for its future headquarters in only 28 hours.

Today, it is possible to print buildings. Thanks to its speed and the variety of architectural forms that it is capable of producing, 3D printing enables us to envisage a more economical and environmentally friendly construction sector.

3D printing consists in reproducing an object modeled on a computer by superimposing layers of material. Also known as “additive manufacturing”, this technique is developing worldwide in all fields, from plastics to medicine, and from food to construction.

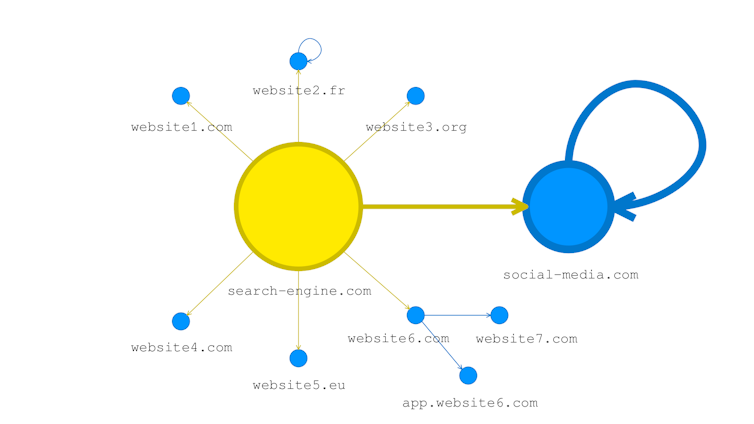

For the 3D printing of buildings, the mortar – composed of cement, water and sand – flows through a nozzle connected to a pump via a hose. The sizes and types of printers vary from one manufacturer to another. The “Cartesian” printer (up/down, left/right, front/back) is one type, which is usually installed in a cage system on which the size of the printed elements is totally dependent. Another type of printer, such as the “maxi printer”, is equipped with a robotic arm and can be moved to any construction site for the direct in situ printing of different structural components in a wider range of object sizes.

Pavilion printed by Constructions 3D in Bruay-sur-l’Escaut. Constructions 3D, provided by the author

Today, concrete 3D printing specialists are operating all over the world, including COBOD in Denmark, Apis Cor in Russia, XtreeE in France and Sika in Switzerland. All these companies share a common goal: promoting the widespread adoption of additive manufacturing for the construction of buildings.

From the laboratory to full scale

3D printing requires mortars with very specific characteristics that enable them to undergo rapid changes.

In fact, these materials are complex and their characterization is still under development: the mortars must be sufficiently fluid to be “pumpable” without clogging the pipe, and sufficiently “extrudable” to emerge from the printing nozzle without blocking it. Once deposited in the form of a bead, the behavior of the mortar must change very quickly to ensure that it can support its own weight as well as the weight of the layers that will be superimposed on it. No spreading or “structural buckling” of the material is permitted, as it could destroy the object. For example, a simple square shape is susceptible to buckling, which could cause the object to collapse, because there is no material to provide lateral support for the structure’s walls. Shapes composed of spirals and curves increase the stability of the object and thus reduce the risk of buckling.

These four criteria (pumpability, extrudability, constructability and aesthetics) define the specifications for cement-based 3D-printing “inks”. The method used to apply the mortar must not be detrimental to the service-related characteristics of the object such as mechanical strength or properties related to the durability of the mortar in question. Consequently, the printing system, compared to traditional mortar application methods, must not alter the performance of the material in terms of both its strength (under bending and compression) and its longevity.

In addition, the particle size and overall composition of the mortar must be adapted to the printing system. Some systems, such as that used for the “Maxi printer”, require all components of the mortar except for water to be in solid form. This means that the right additives (chemicals used to modify the behavior of the material) must then be found. Full-scale printing tests require the use of very large amounts of material.

Initially, small-scale tests of the mortars – also called inks – are carried out in the laboratory in order to reduce the quantities of materials used. A silicone sealant gun can be used to simulate the printing and enable the validation of several criteria. Less subjective tests can then be carried out to measure the “constructable” nature of the inks. These include the “fall cone” test, which is used to observe changes in the behavior of the mortar over time, using a cone that is sunk into the material at regular intervals.

Once the mortars have been validated in the laboratory, they must then undergo full-scale testing to verify the pumpability of the material and other printability-related criteria.

Mini printer. Estelle Hynek, provided by the author

It should be noted that there are as yet no French or European standards defining the specific performance criteria for printable mortars. In addition, 3D-printed objects are not authorized for use as load-bearing elements of a building. This would require certification, as was the case for the Viliaprint project.

Finding replacements for the usual ingredients of mortar for more environmentally friendly and economical inks

Printable mortars are currently mainly composed of cement, a material that is well known for its significant contribution to CO₂ emissions. The key to obtaining more environmentally friendly and economical inks is to produce cement-based inks with a lower proportion of “clinker” (the main component of cement, obtained by the calcination of limestone and clay), in order to limit the carbon impact of mortars and their cost.

With this in mind, IMT Nord-Europe is working on incorporating industrial by-products and mineral additives into these mortars. Examples include “limestone filler”, a very fine limestone powder; “blast furnace slag”, a co-product of the steel industry; metakaolin, a calcinated clay (kaolinite); fly ash, derived from biomass (or from the combustion of powdered coal in the boilers of thermal power plants); non-hazardous waste incineration (NHWI) bottom ash, the residue left after the incineration of non-hazardous waste, or crushed and ground bricks. All of these materials have been used in order to partially or completely replace the binder, i.e. cement, in cement-based inks for 3D printing.

Substitute materials are also being considered for the granular “skeleton” structure of the mortar, usually composed of natural sand. For example, the European CIRMAP project is aiming to replace 100% of natural sand with recycled sand, usually made from crushed recycled concrete obtained from the deconstruction of buildings.

Numerous difficulties are associated with the substitution of the binder and granular skeleton: mineral additions can make the mortar more or less fluid than usual, which will impact the extrudable and constructable characteristics of the ink, and the mechanical strength under bending and/or compression may also be significantly affected depending on the nature of the material used and the cement component substitution rate.

Although 3D printing raises many issues, this new technology enables the creation of bold architectural statements and should reduce the risks present on today’s construction sites.

Estelle Hynek, PhD student in civil engineering at IMT Nord Europe – Institut Mines-Télécom

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (in French).