Flavien Bazenet, Institut Mines-Telecom Business School, (IMT) and Gabriel Périès, Institut Mines-Telecom Business School, (IMT)

This article was written based on the research Augustin de la Ferrière carried out during his “Grande École” training at Institut Mines-Telecom Business School (IMT).

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

[dropcap]« S[/dropcap]afe cities »: seen by some as increasing the security and resilience of cities, others see it as an instance of ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies) being used in the move towards the society of control. The term has sparked much debate. Still, through balanced policies, the “Safe City” could become a part of a comprehensive “smart city” approach. Citizen crowdsourcing (security by citizens) and video analytics—“situational analysis that involves identifying events, attributes or behavior patterns to improve the coordination of resources and reduce investigation time” (source: IBM)—ensure the protection of privacy, and guarantee its cost and performance.

Safe cities and video protection

A “safe city” refers to NICT (New Information and Communication Technology) used for urban security purposes. However, in reality, the term is primarily linked to a marketing concept that major groups integrating the security sector have used to promote their video protection systems.

First appearing in the United Kingdom in the mid-1980s, urban cameras gradually became popularized. While their use is sometimes a subject of debate, in general they are well accepted by citizens, although this acceptance varies based on each country’s risk culture and approach to security matters. Today, nearly 250 million video protection systems are used throughout the world. On an international scale, this translates as one camera for every 30 inhabitants. But the effectiveness of these cameras is often called into question. It is therefore necessary to take a closer look at their role and actual effectiveness.

According to several French reports—in particular the “Report on the effectiveness of video protection by the French Ministry of the Interior, Overseas France and Territorial Communities” (2010) and ”Public policies on video protection: a look at the results” by INHESJ (2015)—the systems appear to be effective primarily in deterring minor criminal offences, reducing urban decay and improving interdepartmental cooperation in investigations.

The effectiveness of video protection limited by technical constraints

On the other hand, video protection has proven completely ineffective in preventing serious offences. The cameras appear only to be effective in confined spaces, and could even have a “publicity effect” for terrorist attacks. These characteristics have been confirmed by analysts in the sector, and are regularly emphasized by Tanguy Le Goff and Eric Heilmann, researchers and experts on this topic.

They also point out that our expectations for these systems are too high, and stress that the technical constraints are too significant, in addition to the excessive installation and maintenance costs.

To better explain the deficiencies in this kind of system, we must understand that in a remotely monitored city, a camera is constantly filming the city streets. It is connected to the “Urban monitoring center”, where the signal is transmitted to several screens. The images are then interpreted by one or more operators. But no human can be legitimately expected to remain concentrated on a multitude of screens for hours at time, especially when the operator-to-screen ratio is often extremely disproportional. In France, the ratio sometimes reaches one operator to one hundred screens! This is why the typical video protection system’s capacity for prevention is virtually nonexistent.

The technical experts imply that the real hope for video protection through forensic science—the ability to provide evidence—is nullified by the obvious technical constraints.

In a “typical” video protection system, the volume of data recorded by each camera is quite significant. According to one manufacturer’s (Axis Communications) estimate, with a camera capable of recording 24 images per second, the generated data ranges from 0.74 Go/hour to 5Go/hour depending on the encoding and chosen resolution. Therefore, the servers are quickly saturated, since current storage capabilities are limited.

With an average cost of approximately 50 euros per terabyte, local authorities and town halls find it difficult to afford datacenters capable of saving video recordings for a sufficient length of time. In France, the CNIL authorizes 30 days of saved video recordings, but in reality, these recordings are rarely saved for more than 7 consecutive days. For some experts, often these saved are not kept for more than 48 hours. Therefore, this undermines the main argument used in favor of video protection: the ability to provide evidence.

A move towards new smart video protection systems?

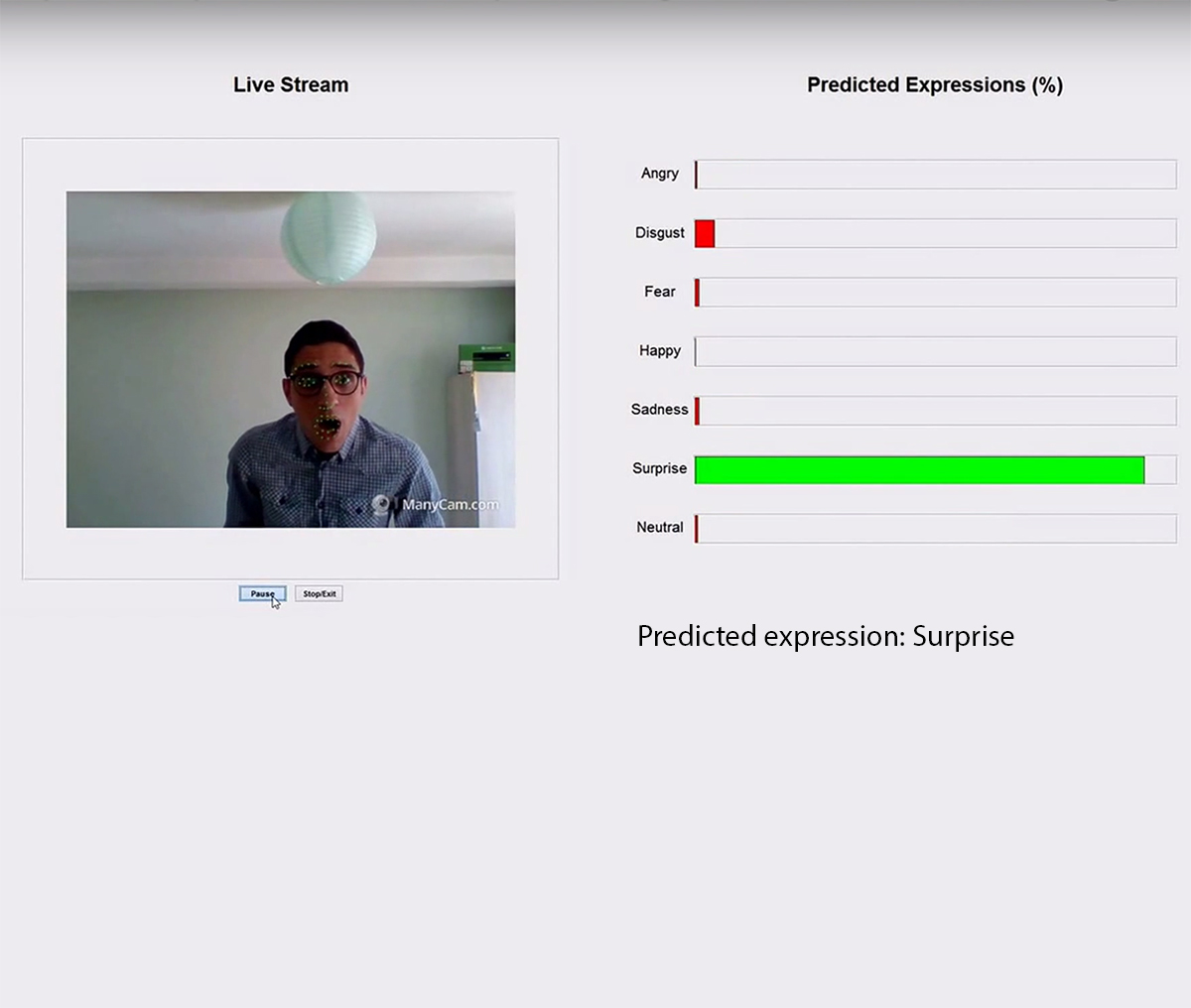

The only viable alternative to the “traditional” video protection system is that of “smart” video protection using video analytics or “VSI”: technology that uses algorithms and pixel analysis.

Since these cameras are generally supported by citizens, they must become more efficient, and not lead to a waste of financial and human resources. “Smart” cameras therefore offer two possibilities: biometric identification and situational analysis. These two components should enable the activation of automatic alarms for operators so that they can take action, which would mean the cameras would truly be used for prevention.

A massive installation of biometric identification is currently nearly impossible in France, since the CNIL is committed to the principles of purpose and proportionality: it is illegal to associate recorded data featuring citizens’ faces without first establishing a precise purpose for the use of this data. The Senate is currently studying this issue.

Smart video protection, safeguarding identity and personal data?

On the other hand, situational analysis offers an alternative that can tap into the full potential of video protection cameras. Through the analysis of situations, objects and behavior, real-time alerts are sent to video protection operators, a feature that restores hope in the system’s prevention capacity. This is in fact the logic behind the very controversial European surveillance project, INDECT: limit the recording of video, to focus only on pertinent information and automated alerts. This technology therefore makes it possible to opt for selective video recording, and even do away with it all together.

VSI with situational analysis could offer some benefits for society, in terms of the effective security measures and the cost of deployment for taxpayers. VSI requires fewer operators than video protection, fewer cameras and fewer costly storage spaces. Referring to the common definition of a “smart city”—realistic interpretation of events, optimization of technical resources, more adaptive and resilient cities—this video protection approach would put “Safe Cities” at the heart of the smart city approach.

Nevertheless, several risks of abuse and potential errors exist, such as unwarranted alerts being generated, and they raise questions about the implementation of such measures.

Citizen crowdsourcing and bottom-up security approaches

The second characteristic of a “smart and safe city” must take people into account, citizens users—the city’s driving force. Security crowdsourcing is a phenomenon that finds its applications in our hyperconnected world through “ubiquitous” technology (smartphones, connected objects). The Boston Marathon bombing (2013), the London riots (2011), the Paris attacks (2015), and various natural catastrophes showed that citizens are not necessarily dependent on central governments, and could ensure their own security, or at least work together with the police and rescue services.

Social networks, Twitter, and Facebook with its “Safety Check” feature, are the main examples of this change. Similar applications quickly proliferated, such as Qwidam, SpotCrime, HeroPolis, and MyKeeper, and are breaking into the protection sector. On the other hand, these mobile solutions are struggling to take any ground in France due to a fear of false information being spread. Yet these initiatives offer true alternatives and should be studied and even encouraged. Without responsible citizens, there can be no resilient cities.

A study from 2016 shows that citizens are likely to use these emergency measures on their smartphones, and that they would make them feel safer.

Since the “smart city” relies on citizen, adaptive and ubiquitous intelligence, it is in our mutual interest to learn from bottom-up governance methods, in which information comes directly from the ground, so that a safe city could finally become a real component of the smart city approach.

Conclusion

Implementing major urban security projects without considering the issues involved in video protection and citizen intelligence leads to a waste of the public sector’s human and financial resources. The use of intelligent measures and the implementation of a citizen security policy would therefore help to create a balanced urbanization policy, a policy for safe and smart cities.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Flavien Bazenet, Associate professor for Entrepreneurship and Innovation at Institut Mines-Telecom Business School, (IMT) and Gabriel Périès, Professor, Department of Foreign languages and Humanities at Institut Mines-Telecom Business School, (IMT)

The original version of this article (in French) was published in The Conversation.

Roland Lehoucq

Roland Lehoucq