Why women have become invisible in IT professions

Female students have deserted computer science schools and women seem mostly absent from companies in this sector. The culprit: the common preconception that female computer engineers are naturally less competent than their male counterparts. The MOOC entitled Gender Diversity in IT Professions*, launched on 8 March 2018, looks at how sexist stereotypes are constructed, often insidiously. Why are women now the minority, rendered invisible in the digital sector despite the many female pioneers and entrepreneurs have paved the way for the development of software and video games? Chantal Morley, a researcher within the Gender@Telecom group at Institut Mines-Telecom Business School, takes a look back at the creation of this MOOC, highlighting the research underpinning the course.

In 2016, only 33% of digital jobs were occupied by women (OPIIEC). Taking into account only the “core” professions in the sector (engineer, technician or project manager), the percentage falls to 20%. Why is there such a gender gap? No, it’s not because women are less talented in technical professions, nor because they prefer other areas. The choices made by young women in their training and women in their careers is not always the result of a free and informed decision. The influence of stereotypes plays a significant role. These popular beliefs reinforce the idea that the IT field is inherently masculine, a place where women do not belong, and this influences our choices and behaviors even when we do not realize it.

The research group Gender@Telecom, which brings together several female researchers from IMT schools, is looking at the issue of women’s role in the field of information and communication technologies, and specifically the software sector. Through their studies and analysis, the group’s researchers have observed and described how these stereotypes are expressed. “We interviewed professionals in the sector, and asked students specific questions about their choices and opinions,” explains Chantal Morley, researcher at Institut Mines-Telecom Business School. By analyzing the speech from those interviews, the researchers identified many preconceived notions. “Women do not like computer science, it does not interest them, for example,” the researcher continues. “These representations are unproven and do not match reality!” These little phrases that communicate stereotypes are heard from both men and women. “One might think that this type of differentiation in representations would not exist among male and female students, but that is not the case,” says Chantal Morley. “During a study conducted in Switzerland, we found that guidance counselors are also very much influenced by these stereotypes.” Among professionals, these views are even cited as arguments justifying certain choices.

Little phrases, big impacts

The Gender Diversity in IT Professions MOOC* developed by the Gender@Telecom group is aimed at deconstructing these stereotypes. “We used these studies to try to show learners how little things in everyday life, which we do not even notice, contribute to instilling these differentiated views,” Chantal Morley explains. These little phrases or representations can also be found in our speech as well as in advertisements, posters… When viewed individually, these small occurrences are insignificant, yet it is their repetition and systematic nature that pose a problem. Together they work to establish and reinforce sexist stereotypes. “They form a common knowledge, a popular belief that everyone is aware of, that we all accept, saying ‘that’s just the way it is!’”

To study this phenomenon, the researchers from the group analyzed speech from semi-structured interviews conducted with stakeholders in the digital industry. The researchers’ questions focused on the relationship with technology and an entrepreneurship competition that had recently been held at Institut Mines-Telecom Business School. “Again, in this study, some types of arguments were frequently repeated and helped reinforce these stereotypes,” Chantal Morley observes. “For example, when someone mentions a woman who is especially talented, the person will often add, ‘yes, but with her it’s different, that doesn’t count.’ There is always an excuse for not questioning the general rule that says women lack the abilities required in digital professions.”

Unjustified stereotypes

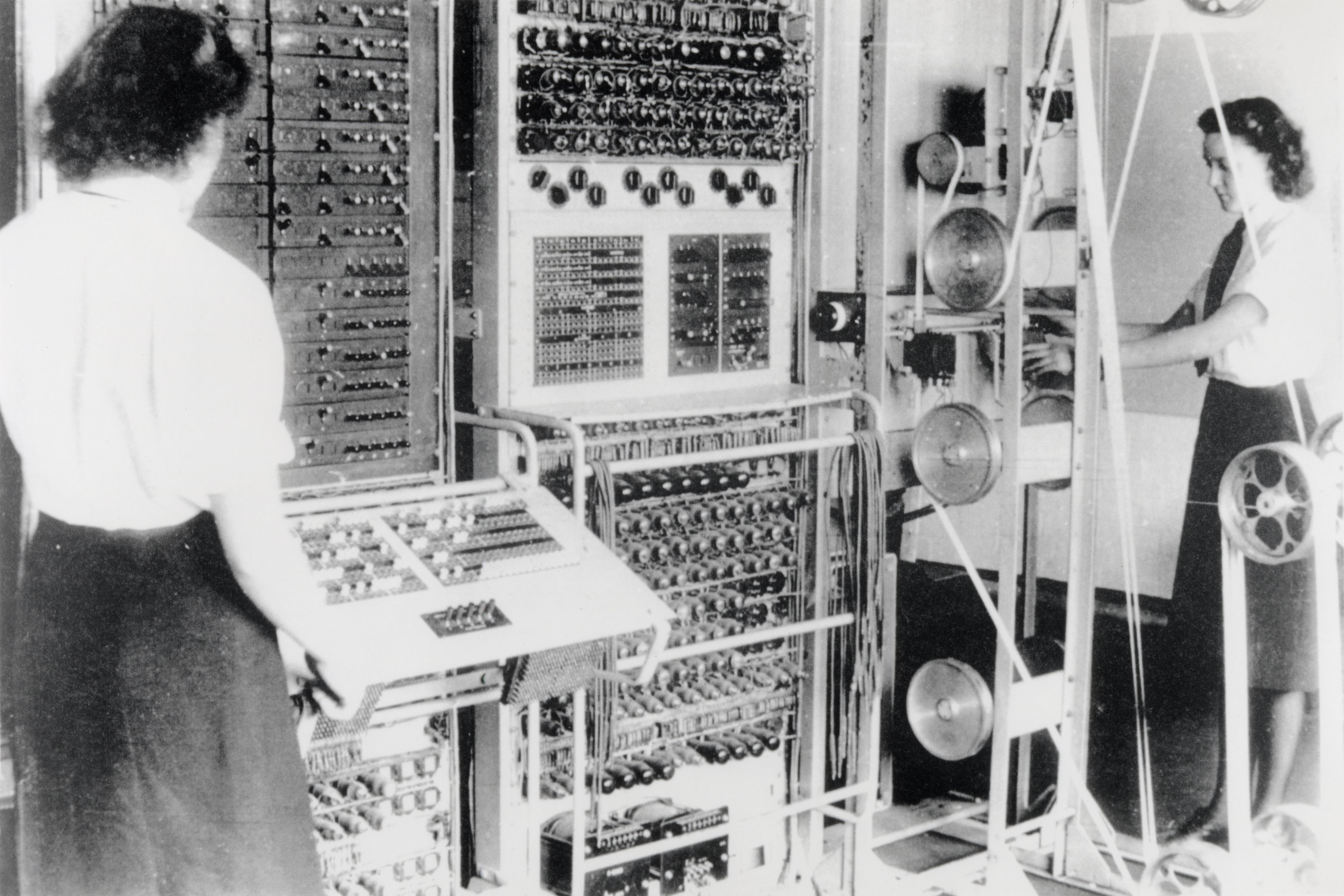

Yet despite their pervasiveness, there is nothing to justify these remarks. The history of computer science professions proves this fact. However, the contribution of women has long been hidden behind the scenes. “When we studied the history of computer science, we were primarily looking at the area of hardware, equipment. Women were systematically rejected by universities and schools in this field, where they were not allowed to earn a diploma,” says Chantal Morley. “Also, some companies refused to keep their employees if they had a child or got married. This made careers very difficult.” In recent years, research on the history of the software industry, in which there were more opportunities, has revealed that many women contributed to major aspects of its development.

“Ada Lovelace is sort of the Marie Curie of computer science… People think she is the only one! Yet she is one contributor among others,” the researcher explains. For example, the computer scientist Grace Hopper invented the first compiler and the COBOL language in the 1950s. “She had the idea of inventing a translator that would translate a relatively understandable and accessible language into machine language. Her contribution to programming was crucial,” Chantal Morley continues. “We can also mention Roberta Williams, a computer scientist who greatly contributed to the beginnings of video games, or Stephanie Shirley, a pioneer computer scientist and entrepreneur…”

In the past these women were able to fight for their place in software professions. What has happened to make women seem absent from these arenas? According to Chantal Morley, the exclusion of women occurred with the arrival of microcomputing, which at the time had been designed for a primarily male target, that of executives. “The representations conveyed at that time progressively led everyone to associate working with computers with men.” But although women are a minority in this sector, they are not completely absent. “Many have participated in the creation of very large companies, they found startups, and there are some very famous women hackers,” Chantal Morley observes. “But they are not at all in the spotlight and do not get much press coverage. As if they were an anomaly, something unusual…”

Finally, women’s role in the digital industry varies greatly depending on the country and culture. In India and Malaysia, for example, computer science is a “women’s” profession. It is all a matter of perspective, not a question of innate abilities.

[box type=”shadow” align=”” class=”” width=””]*A MOOC combating sexist stereotypes

How are these stereotypes constructed and maintained? How can they be deconstructed? How can we promote the integration of women in digital professions? The Gender Diversity in IT Professions MOOC (in French), launched on 8 March 2018, uncovers the little-known contribution of women to the development of the software industry and what mechanisms cause them to remain hidden and discouraged from integrating this sector. The MOOC is aimed at raising awareness among companies, schools and research organizations on these issues to provide them with keys for developing a more inclusive culture for women. [/box]

Also read on I’MTech