Production line flexibility: human operators to the rescue!

Changing customer needs have cast a veil of uncertainty over the future of industrial production. To respond to these demands, production systems must be flexible. Although industry is becoming increasingly automated, a good way to provide flexibility is to reintroduce human operators. An observation that goes against current trends, presented by Xavier Delorme, an industrial management researcher at Mines Saint-Étienne at the IMT symposium on “Production Systems of the Future”.

This article is part of our series on “The future of production systems, between customization and sustainable development.”

Automation, digitization and robotization are concepts associated with our ideas about the industry of the future. With a history marked by technological and technical advances, industry is counting on autonomous machines that make it possible to produce more, faster. Yet, this sector is now facing another change: customer needs. A new focus on product customization is upending how production systems are organized. The automotive industry is a good example of this new problem. Until now, it has invested in production lines that would be used for ten to twenty years. But today, the industry has zero visibility on the models it will produce over such a period of time. A production system that remains unchanged for so long is no longer acceptable.

In order to meet a wide range of customer demands that impact many steps of their production, companies must have flexible manufacturing systems. “That means setting up a system that can evolve to respond to demands that have not yet been identified – flexibility – so that it can be adjusted by physically reconfiguring the system more or less extensively,” explains Xavier Delorme, a researcher at Mines Saint-Étienne. Flexibility can be provided through digital controls or reprogramming a machine, for example.

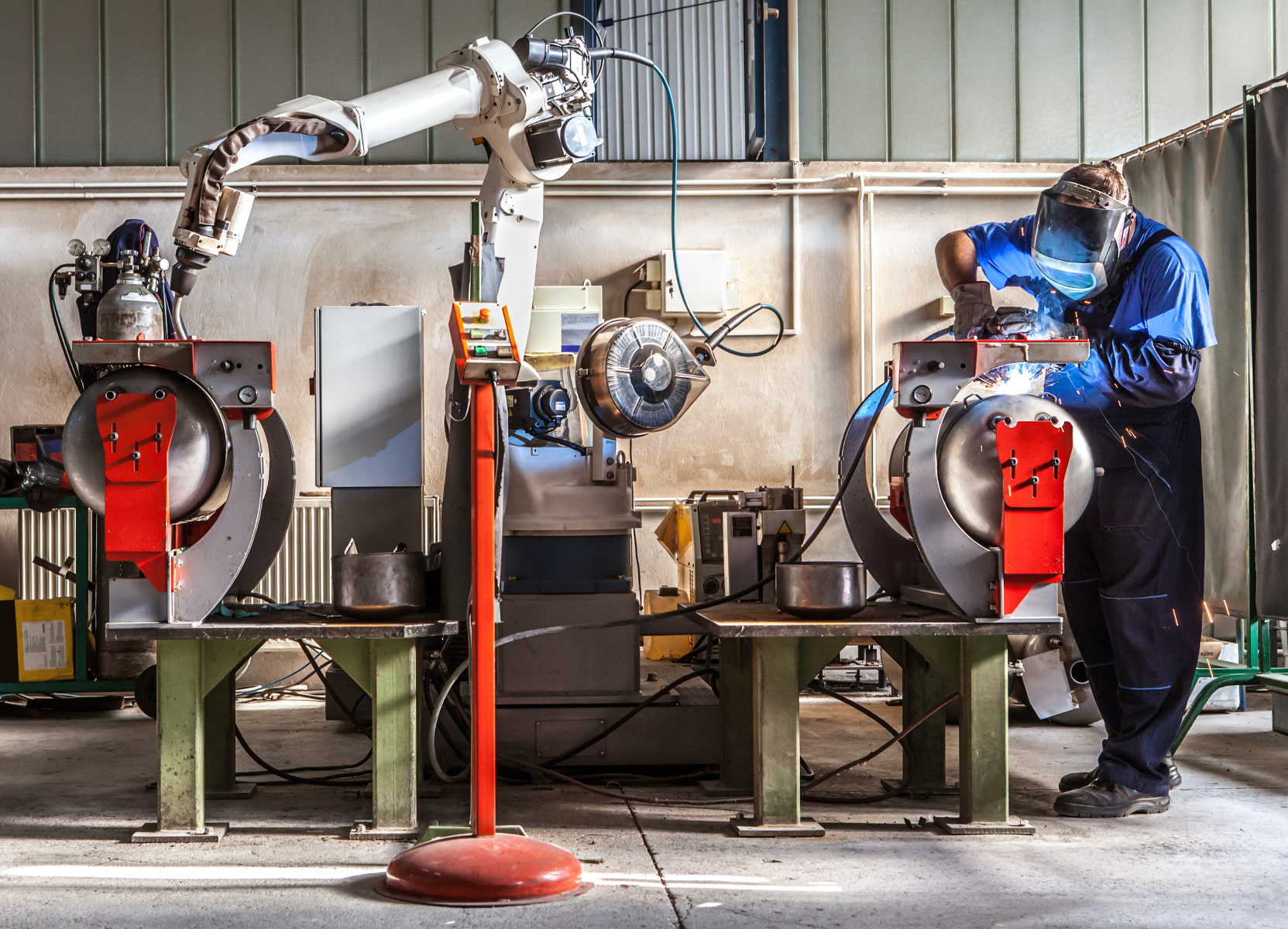

But in this increasingly machine-dominated environment, “another good way to provide flexibility is to reintroduce versatile human operators, who have an ability to adapt,” says the researcher. The primary aim of his work is to leverage each side’s strengths, while attempting to limit the weaknesses of the other side. He proposes software solutions to help design production lines and ensure that they run smoothly.

Versatility of human operators

This conclusion is based on field observations, in particular through collaboration with MBtech Group, in which the manufacturer drew attention to this problem. The advanced automation of its production lines was reducing versatility. The solution proposed by researchers: reintroduce human operators. “We realized that some French companies had conserved this valuable resource, although they were often behind in terms of automation. There’s a balance to be found between these two elements,” says Xavier Delorme. It appears that the best way to create value, in terms of economic efficiency and flexibility, is to combine robots and humans in a complementary manner.

A system that produces engines manufactures different models but does not need to be modified for each variant. It adapts to the product, switching almost instantaneously from one to another. However, the workload for different stations varies according to the model. This classic situation requires versatility. “A well-trained, versatile human operator reorganizes his work by himself. He repositions himself as needed at a given moment; this degree of autonomy doesn’t exist in current automated systems, which cannot be moved quickly from one part of the production line to another,” says Xavier Delorme.

This flexibility presents a twofold problem for companies. Treating an operator like a machine reduces his range of abilities which does result in efficiency. It is therefore in companies’ interest to enhance operators’ versatility through training and assigning them various tasks in different parts of the production system. But the risk of turnover and the loss of skills associated with short contracts and frequent changes in staff still remain.

The arduous working conditions of multifunctional employees must also not be overlooked. This issue is usually considered too late in the design process, leading to serious health problems and malfunctions in production systems. “That’s why we also focus on workstation ergonomics starting in the design stage,” explains Xavier Delorme. The biggest health risks are primarily physical: fatigue due to a poor position, repetitiveness of tasks etc. The versatility of human operators can reduce these risks, but it can also contribute to them. Indeed, the risks increase if an employee lacks experience and finds it difficult to carry out tasks at different workstations. Once again, the best solution is to find the right balance.

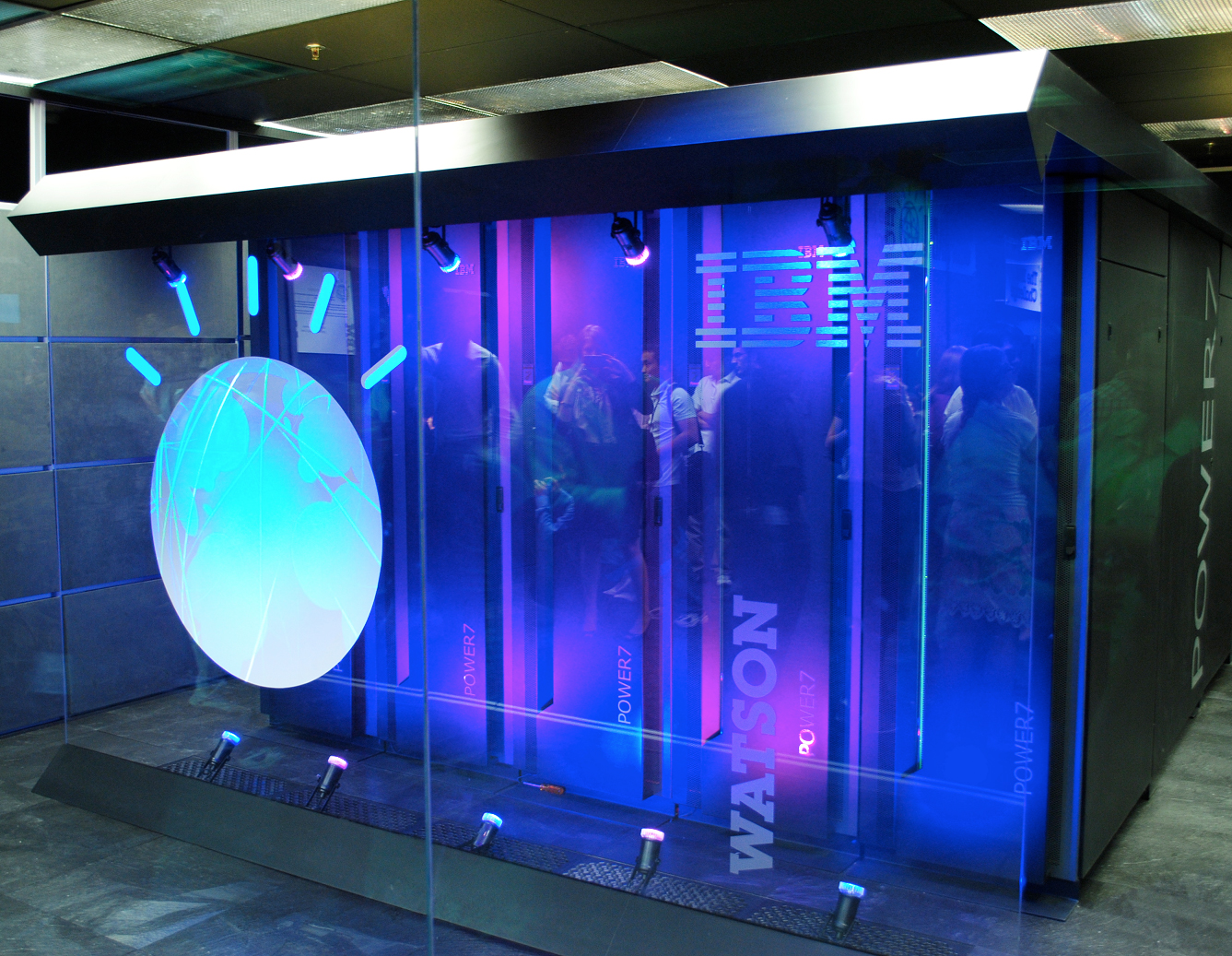

Educating SMEs about the industry of the future

“Large corporations are already on their way to the industry of the future, but it’s more difficult for SMEs,“ says Xavier Delorme. In June 2018, Mines Saint-Étienne researchers launched IT’mFactory, an educational platform developed in partnership with the Union des industries et métiers de la métallurgie (Union of Metallurgy Industries). This demonstration tool makes it possible to connect with SMEs to discuss the challenges and possibilities presented by the industry of the future. It also provides an opportunity to address problems facing SMEs and direct them towards appropriate innovations.

Such interactions are precious in a time in which production methods are undergoing considerable changes (cloud manufacturing, additive manufacturing, etc.) The business models involved provide researchers with new challenges. And flexibility alone will not respond to the needs of customization — or how to produce by the unit and on demand. Servicization, which sells a service associated with a product, is also radically changing the ways in which companies have to be organized.

Article written by Anaïs Culot, for I’MTech.

En attendant les robots, enquête sur le travail du clic (Waiting for Robots, an Inquiry into Click Work)

En attendant les robots, enquête sur le travail du clic (Waiting for Robots, an Inquiry into Click Work)