Bitcoin crash: cybercrime and over-consumption of electricity, the hidden face of cryptocurrency

Donia Trabelsi, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School ; Michel Berne, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School et Sondes Mbarek, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School

Wednesday 19 May will be remembered as the day of a major cryptocurrency crash: -20% for dogecoin, -19% for ethereum, -22% for definity, the supposedly-infinite blockchain that was recently launched with a bang. The best-known of these currencies, bitcoin, limited the damage to 8.5% (US $39,587) after being down by as much as 30% over the course of the day. It is already down 39% from its record value reached in April.

Very few of the 5,000 cryptocurrencies recorded today have experienced growth. The latest ones to be launched, “FuckElon” and “StopElon”, say a lot about the identity of the individual considered to be responsible for this drop in prices set off over a week ago.

The former idol of the cryptocurrency world and iconic leader of Tesla Motors, Elon Musk, now seems to be seen as a new Judas by these markets. The founders of “StopElon” have even stated that their aim is to drive up the price of their new cryptocurrency in order to buy shares in Tesla and oust its top executive. However, bitcoin’s relatively smaller drop seems to be attributed to its reassuring signals.

Elon Musk sent shockwaves rippling through the crypto world last week when he announced that it would no longer be possible to pay for his cars in bitcoin, reversing the stance he had taken in March. He even hinted that Tesla may sell all of its bitcoins. As the guest host of the Saturday Night Live comedy show in early May, he had already caused the dogecoin to plummet, though he had appeared on the show to support it, by referring to it as a “hustle” during a sketch.

here’s a clip of elon musk explaining what doge coin is on SNL….he said it’s a hustle

pic.twitter.com/iyXbKH0FPZ

— niffauw (@RustigNiffauw) May 9, 2021

The reason for his change of heart? The fact that it is harmful to the planet, as transactions using this currency require high electricity consumption. “Cryptocurrency is a good idea on many levels and we believe it has a promising future, but this cannot come at great cost to the environment,” stated Musk, who is also the head of the SpaceX space projects.

China also appears to have played a role in Wednesday’s events. As the country is getting ready to launch a digital yuan, its leaders announced that financial institutions would be prohibited from using cryptocurrency. “After Tesla’s about-face, China twisted the knife by declaring that virtual currencies should not and cannot be used in the market because they are not real currencies,” declared Fawad Razaqzada, analayst at Thinkmarkets, to AFP yesterday.

While a single man’s impact on the price of these assets – which have seen a dramatic rise over the course of a year – may be questioned, his recent moves and about-face urge us to at least examine the ethical issues they raise. Our research has shown that there at least two categories of issues.

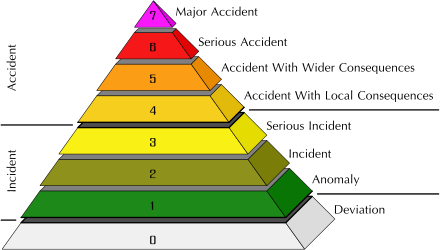

The darknet and ransomware

The ethical issues surrounding cryptocurrencies remain closely related to the nature and very functioning of these assets. Virtual currencies are not associated with any governmental authority or institution. The bitcoin system was even specifically designed to avoid relying on conventional trusted intermediaries, such as banks, and escape the supervision of central banks. The value of a virtual currency therefore relies entirely, in theory, on the trust and honesty of its users, and on the security of an algorithm that can track all of the transactions.

Yet, due to their anonymity, lack of strict regulation and gaps in infrastructure, cryptocurrencies also appear to be likely to attract groups of individuals who seek to use them in a fraudulent way. Regulatory concerns focus on their use in illegal trade (drugs, hacking and theft, illegal pornography), cyberattacks and their potential for funding terrorism, laundering money and evading taxes.

Illegal activities accounted for no less than 46% of bitcoin transactions from 2009 to 2017, amounting to US $76 billion per year over this period, which is equivalent to the scale of US and European markets for illegal drugs. In April 2017, approximately 27 million bitcoin market participants were using bitcoin primarily for illegal purposes.

One of the best-known examples of cybercrime involving cryptocurrency is still the “Silk Road.” In this online black marketplace dedicated to selling drugs on the darknet, the part of the internet that can only be accessed with specific protocols, payments are made exclusively in cryptocurrencies.

In 2014, at a time when the price of the bitcoin was around US $150, the FBI’s seizure of over US $4 million in bitcoins on the Silk Road gives an idea of the magnitude of the problem facing regulators. At the time, the FBI estimated that this sum accounted for nearly 5% of the total bitcoin economy.

Cryptocurrencies have also facilitated the spread of attacks using ransomware, malware that blocks companies’ access to their own data, and will only unblock it in exchange for a cryptocurrency ransom payment. A study carried out by researchers at Google revealed that victims paid over US $25 million in ransom between 2015 and 2016. In France, according to a Senate report submitted in July 2020, such ransomware attacks represent 8% of requests for assistance from professionals on the cybermalveillance.gouv.fr website and 3% of requests from private individuals.

Energy-intensive assets

The main cryptocurrencies use a large quantity of electricity for mining, meaning IT operations in order to make them and verify transactions. The two main virtual currencies, bitcoin and ethereum, require complicated calculations that are extremely energy-intensive.

According to Digiconomist, for bitcoin, the peak energy consumption was between 60 and 73 TWh in October 2018. On an annualized basis, in mid-April 2021, this figure is somewhere between 50 and 120 TWh, which is higher than the energy consumption of a country such as Kazakhstan. These figures are even more staggering when they are given per transaction: on 6 May 2019, the figure was 432 KWh per transaction and over 1,000 KWh in mid-April 2021, which is equivalent to the annual consumption of a 30m2 studio apartment in France.

A comparison is often made with the Visa electronic payment system, which requires roughly 300,000 less energy consumption than bitcoin for each transaction. The figures cannot be strictly compared, but clearly show that bitcoin transactions are extremely energy-intensive compared to routine electronic transactions.

How can we find a balance?

There are solutions to reduce the cost and energy impact of bitcoins, such as using green energy or increasing the energy efficiency of mining computers.

However, computer technology must still be improved to make this possible. Most importantly, the miners’ reward for mining new bitcoins and verifying transactions is expected to decrease in the future, forcing them to consume more energy to ensure the same level of income.

The initiators of this technology consider that the innovation offered by bitcoin promotes a free world market and connects the world financially. However, it remains a challenge to find the right balance between promoting an innovative technology and deterring the crime and reducing the ecological impact associated with it.

Donia Trabelsi, associate professor of finance, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School; Michel Berne, Economist, director of training (retired), Institut Mines-Télécom Business School and Sondes Mbarek, associate professor of finance, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School

This article was republished from the The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (in French).