Artificial Intelligence: the complex question of ethics

The development of artificial intelligence raises many societal issues. How do we define ethics in this area? Armen Khatchatourov, a philosopher at Télécom École de Management and member of the IMT chair “Values and Policies of Personal Information”, observes and carefully analyzes the proposed answers to this question. One of his main concerns is the attempt to standardize ethics using legislative frameworks.

In the frantic race for artificial intelligence, driven by GAFA[1], with its increasingly efficient algorithms and ever-faster automated decisions, engineering is king, supporting this highly-prized form of innovation. So, does philosophy still have a role to play in this technological world that places progress at the heart of every objective? Perhaps that of a critical observer. Armen Khatchatourov, a researcher in philosophy at Télécom École de Management, describes his own approach as acting as “an observer who needs to keep his distance from the general hype over anything new”. Over the past several years he has worked on human-computer interactions and the issues of artificial intelligence (AI), examining the potentially negative effects of automation.

In particular, he analyses the problematic issues arising from legal frameworks established to govern AI. His particular focus is on “ethics by design”. This movement involves integrating the consideration of ethical aspects at the design stage for algorithms, or smart machines in general. Although this approach initially seems to reflect the importance that manufacturers and developers may attach to ethics, according to the researcher, “this approach can paradoxically be detrimental.”

Ethics by design: the same limitations as privacy by design?

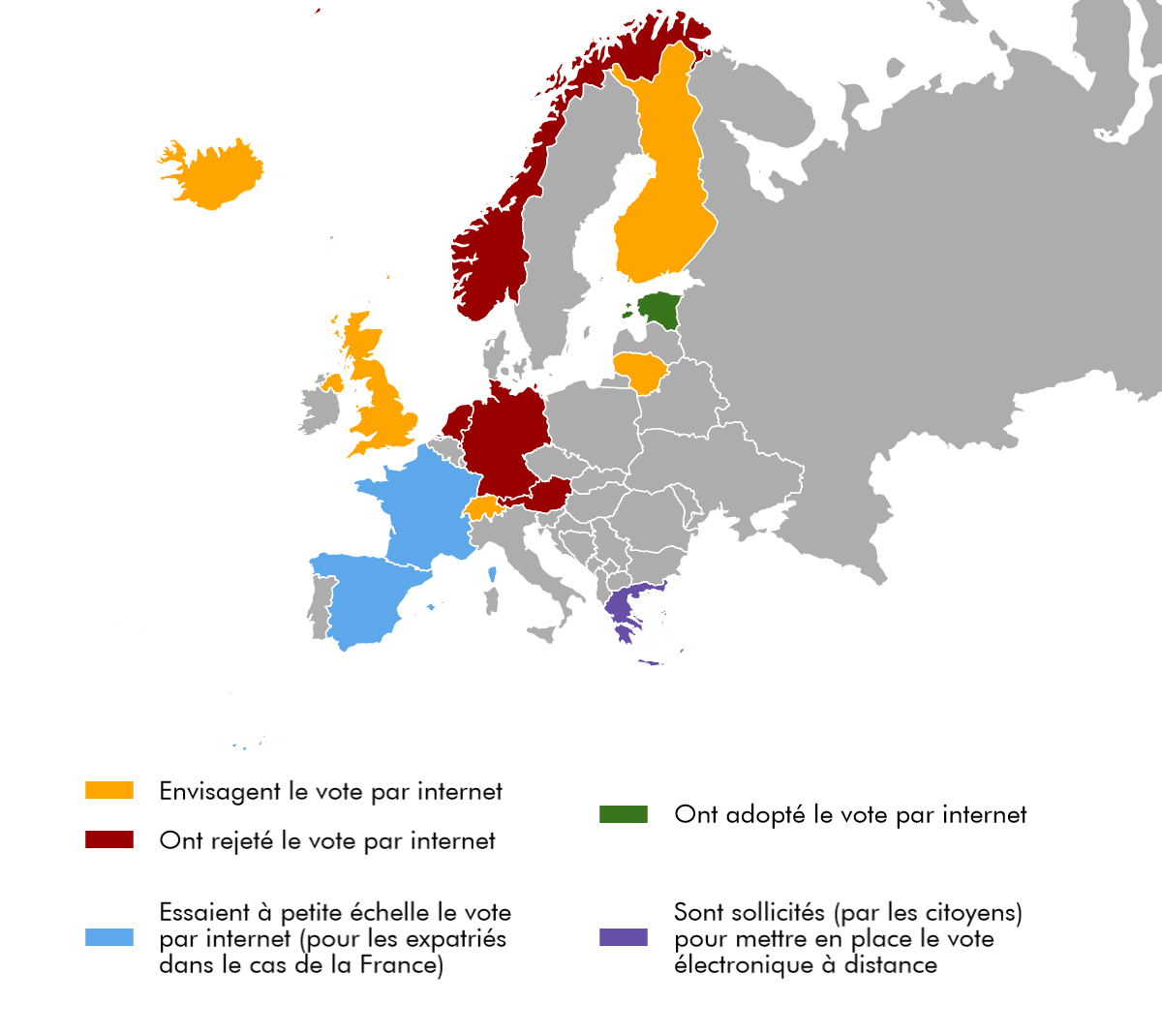

To illustrate his thinking, Armen Khatchatourov uses the example of a similar concept – the protection and privacy of personal information: just like ethics, this subject raises the issue of how we treat other people. “Privacy by design” appeared near the end of the 1990s, in reaction to legal challenges in regulating digital technology. It was presented as a comprehensive analysis of how to integrate the issues of personal information protection and privacy into product development and operational processes. “The main problem is that today, privacy by design has been reduced to a legal text,” regrets the philosopher, referring to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) adopted by European Parliament. “And the reflections on ethics are heading in the same direction,” he adds.

There is the risk of losing our ability to think critically.

In his view, the main negative aspect of this type of standardized regulation implemented via a legal text is that it eliminates the stakeholders’ feeling of responsibility. “On the one hand, there is the risk that engineers and designers will be happy simply to agree with the text,” he explains. “On the other hand, the consumers will no longer think about what they are doing, and trust the labels attributed by regulators.” Behind this standardization, “there is the risk of losing our ability to think critically.” And he concludes by asking “Do we really think about what we’re doing every day on the Web, or are we simply guided by the growing tendency toward normativeness.”

The same threat exists for ethics. The mere fact of formalizing it in a legal text would work against the reflexivity it promotes. “This would bring ethical reflection to a halt,” warns Armen Khatchatourov. He expands on his thinking by referring to work done by artificial intelligence developers. There always comes a moment when the engineer must translate ethics into a mathematical formula to be used in an algorithm. In practical terms, this can take the form of an ethical decision based on a structured representation of knowledge (ontology, in computer language). “But things truly become problematic if we reduce ethics to a logical problem!” the philosopher emphasizes. “For a military drone, for example, this would mean defining a threshold for civilian deaths, below which the decision to fire is acceptable. Is this what we want? There is no ontology for ethics, and we should not take that direction.”

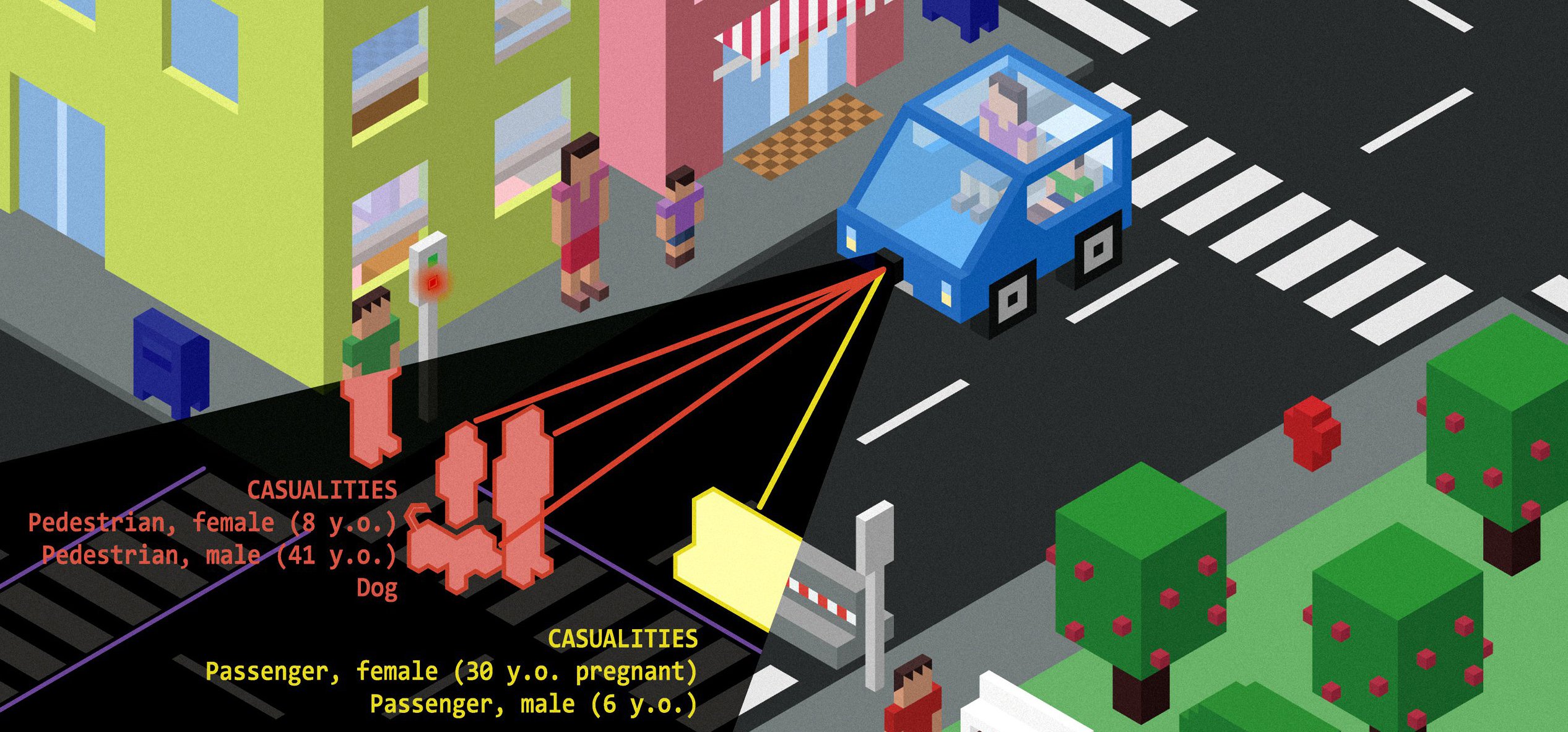

And military drones are not the only area involved. The development of autonomous, or driverless, cars involves many questions regarding how a decision should be made. Often, ethical reflections pose dilemmas. The archetypal example is that of a car heading for a wall that it can only avoid by running over a group of pedestrians. Should it sacrifice its passenger’s life, or save the passenger at the expense of the pedestrians’ lives? There are many different arguments. A pragmatic thinker would focus on the number of lives. Others would want the car to save the driver no matter what. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has therefore developed a digital tool – the Moral Machine – which presents many different practical cases and gives choices to Internet users. The results vary significantly according to the individual. This shows that, in the case of autonomous cars, it is impossible to establish universal ethical rules.

Ethics are not a product

Still according to the analogy between ethics and data protection, Armen Khatchatourov brings up another point, based on the reflections of Bruce Schneier, a specialist in computer security. He describes computer security as a process, not a product. Consequently, it cannot be completely guaranteed by a one-off technical approach, or by a legislative text, since both are only valid at certain point in time. Although updates are possible, they often take time and are therefore out of step with current problems. “The lesson we can learn from computer security is that we cannot trust a ready-made solution, and that we need to think in terms of processes and attitudes to be adopted. If we make the comparison, the same can be said for the ethical issues raised by AI,” the philosopher points out.

This is why it is advantageous to think about the framework for processes like privacy and ethics in a different context than the legal one. Yet Armen Khatchatourov recognizes the need for these legal aspects: “A regulatory text is definitely not the solution for everything, but it is even more problematic if no legislative debate exists, since the debate reveals a collective awareness of the issue.” This clearly shows the complexity of a problem to which no one has yet found a solution.

[1] GAFA: an acronym for Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon.

[box type=”shadow” align=”” class=”” width=””]

Artificial intelligence at Institut Mines-Télécom

The 8th Fondation Télécom brochure, published (in French) in June 2016, is dedicated to artificial intelligence (AI). It presents an overview of the research taking place in this area throughout the world, and presents the vast body of research underway at Institut Mines-Télécom schools. In 27 pages, this brochure defines intelligence (rational, naturalistic, systematic, emotional, kinesthetic…), looks back at the history of AI, questions its emerging potential, and looks at how it can be used by humans.[/box]

An associate research professor in economics at Télécom Bretagne,

An associate research professor in economics at Télécom Bretagne,