Emergency logistics for field hospitals

European field hospitals, or temporary medical care stations, are standing by and ready to be deployed throughout the world in the event of a major disaster. The HOPICAMP project, of which IMT Mines Alès is one of the partners, works to improve the logistics of these temporary medical centers and develop telemedicine tools and training for health care workers. Their objective is to ensure the emergency medical response is as efficient as possible. The logistical tools developed in the context of this project were successfully tested in Algeria on 14-18 April during the European exercise EU AL SEISMEEX.

European field hospitals, or temporary medical care stations, are standing by and ready to be deployed throughout the world in the event of a major disaster. The HOPICAMP project, of which IMT Mines Alès is one of the partners, works to improve the logistics of these temporary medical centers and develop telemedicine tools and training for health care workers. Their objective is to ensure the emergency medical response is as efficient as possible. The logistical tools developed in the context of this project were successfully tested in Algeria on 14-18 April during the European exercise EU AL SEISMEEX.

Earthquakes, fires, epidemics… Whether the disasters are of natural or human causes, European member states are ready to send resources to Africa, Asia or Oceania to help the affected populations. Field hospitals, temporary and mobile stations where the wounded can receive care, represent a key element in responding to emergencies.

“After careful analysis, we realized that the field hospitals could be improved, particularly in terms of research and development,” explains Gilles Dusserre, a researcher at IMT Mines Alès, who works in the area of risk science and emergency logistics. This multidisciplinary field, at the crossroads between information technology, communications, health and computer science, is aimed at improving the understanding of the consequences of natural disasters on humans and the environment. “In the context of the HOPICAMP project, funded by the Single Interministerial Fund (FUI) and conducted in partnership with the University of Nîmes, the SDIS30 and companies CRISE, BEWEIS, H4D and UTILIS, we are working to improve field hospitals, particularly in terms of logistics,” the researcher explains.

Traceability sensors, virtual reality and telemedicine to the rescue of field hospitals

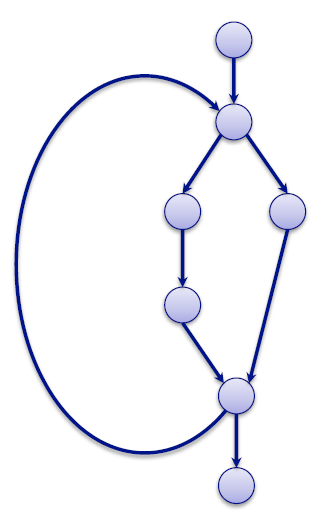

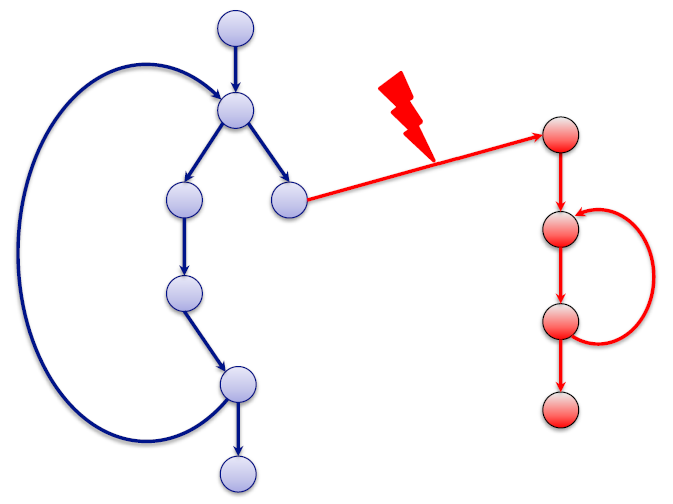

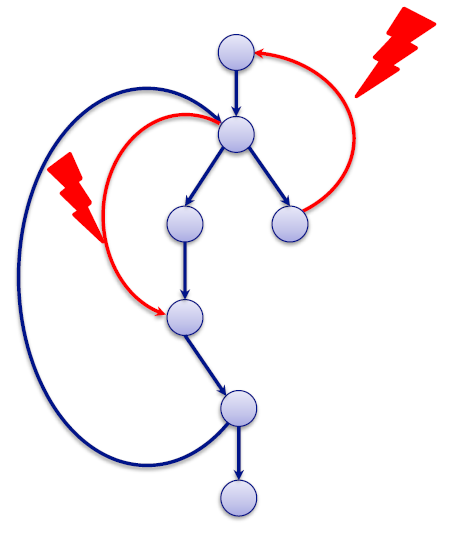

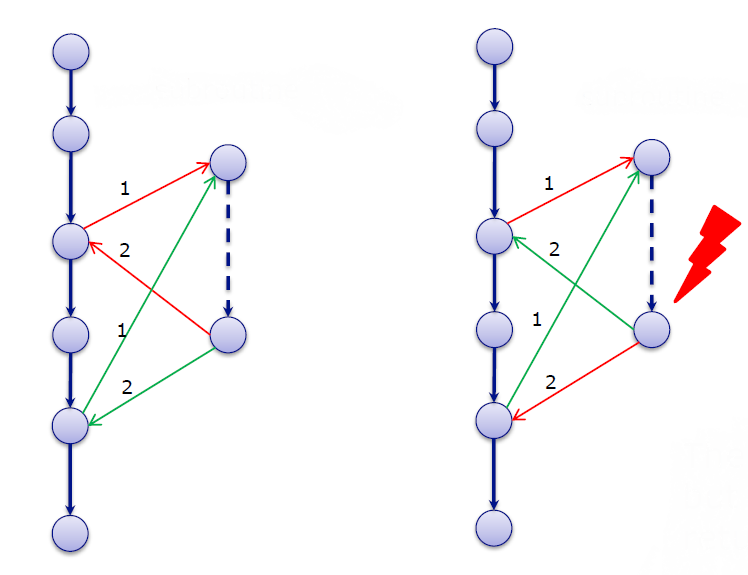

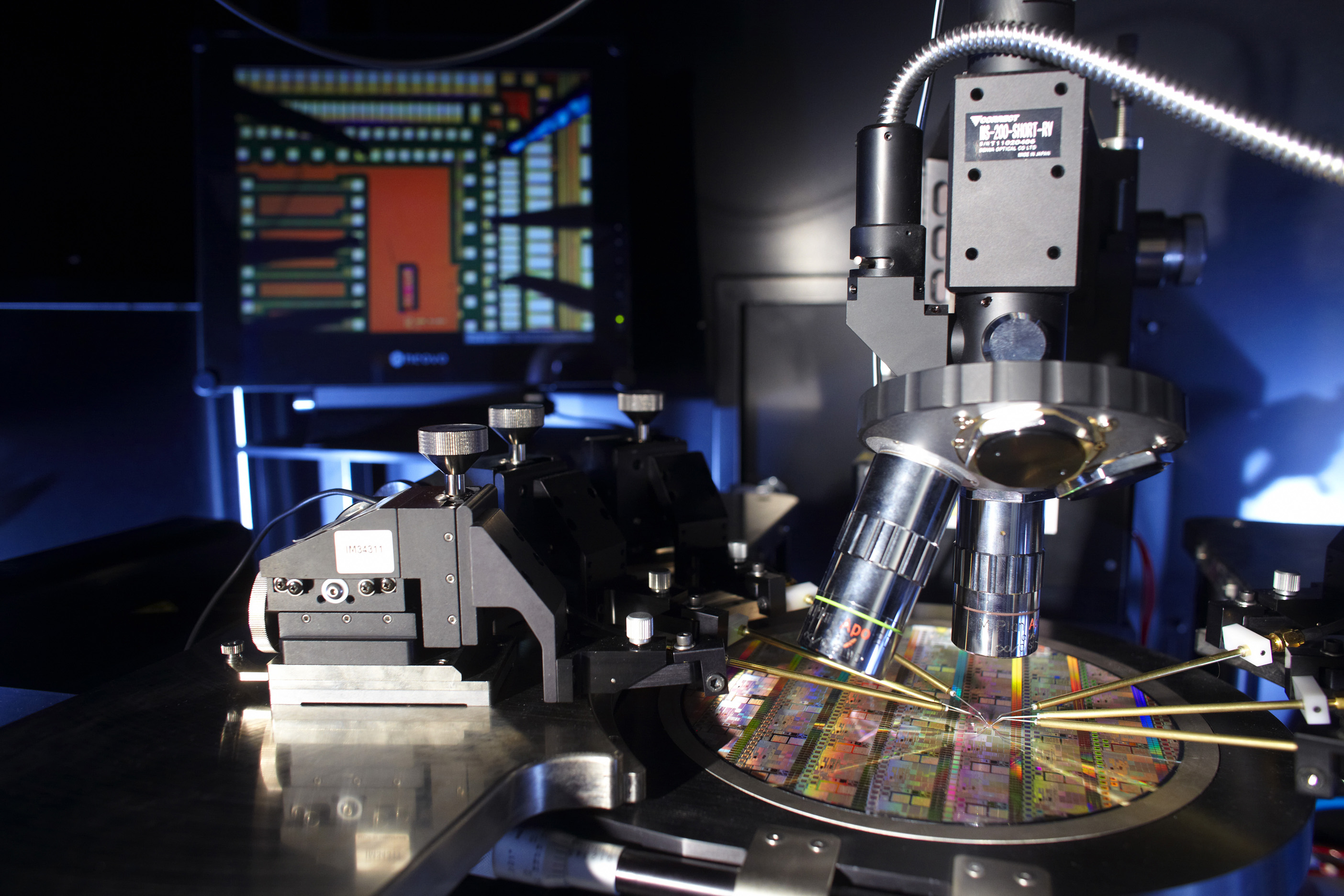

When a field hospital is not being deployed, all the tents and medical equipment are stored in crates, which makes it difficult to ensure the traceability of critical equipment. For example, an electrosurgical unit must never be separated from its specific power cable due to risks of not being able to correctly perform surgical operations in the field. “The logistics operational staff are all working on improving how these items are addressed, identified and updated, whether the hospital is deployed or on standby,” Gilles Dusserre explains. The consortium worked in collaboration with BEWEIS to develop an IT tool for identification and updates as well as for pairing RFID tags, sensors that help ensure the traceability of the equipment.

In addition, once the hospital is deployed, pharmacists, doctors, engineers and logisticians must work in perfect coordination in emergency situations. But how can they be trained in these specific conditions when their workplace has not yet been deployed? “At IMT Mines Alès, we decided to design a serious game and use virtual reality to help train these individuals from very different professions for emergency medicine,” explains Gilles Dusserre. Thanks to virtual reality, the staff can learn to adapt to this unique workplace, in which operating theaters and treatment rooms are right next to living quarters and rest areas in tents spanning several hundred square meters. The serious game, which is being developed, is complementary to the virtual reality technology. It allows each participant to identify the different processes involved in all the professions to ensure optimal coordination during a crisis situation.

Finally, how can the follow-up of patients be ensured when the field hospitals are only present in the affected countries for a limited time period? “During the Ebola epidemic, only a few laboratories in the world were able to identify the disease and offer certain treatments. Telemedicine is therefore essential here,” Gilles Dusserre explains. In addition to proposing specific treatments to certain laboratories, telemedicine also allows a doctor to remotely follow-up with patients, even when the doctor has left the affected area. “Thanks to the company H4D, we were able to develop a kind of autonomous portable booth that allows us to observe around fifteen laboratory values using sensors and cameras.” These devices remain at the location, providing the local population with access to dermatological, ophthalmological and cardiological examinations through local clinics.

Field-tested solutions

“We work with the Fire brigade Association of the Gard region, the French Army and Doctors Without Borders. We believe that all of the work we have done on feedback from the field, logistics, telemedicine and training has been greatly appreciated,” says Gilles Dusserre.

In addition to being accepted by end users, certain tools have been successfully deployed during simulations. “Our traceability solutions for equipment developed in the framework of the HOPICAMP project were tested during the EU AL SEISMEEX Europe-Algeria earthquake deployment exercises in the resuscitation room,” the researcher explains. The exercise, which took place from April 14-18 in the context of a European project funded by DG ECHO, the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, simulated the provision of care for victims of a fictional earthquake in Bouira, Algeria. 1,000 individuals were deployed for the 7 participating countries: Algeria, Tunisia, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Poland and France. The field hospitals from the participating countries were brought together to cooperate and ensure the interoperability of the implemented systems, which can only be tested during actual deployment.

Gilles Dusserre is truly proud to have led a project that contributed to the success of this European simulation exercise. “As a researcher, it is nice to be able to imagine and design a project, see an initial prototype and follow it as it is tested and then deployed in an exercise in a foreign country. I am very proud to see what we designed becoming a reality.”