Do hospital staff feel prepared?

Marie Bossard, a specialist in the social psychology of health, has been studying the feeling of preparedness among hospital staff in the face of exceptional health situations in her PhD since 2018. She explores the factors that may influence this feeling to better understand the dynamics of preparation in health systems.

The Covid-19 crisis is a case in point: our care system must sometimes confront exceptional health situations. Hospital staff are trained to respond to such situations, but there is little scientific literature on the way in which those concerned perceive their preparation. So how do caregivers, medical doctors, administrative staff and medical center directors feel in the face of these exceptional situations? This is the subject of Marie Bossard’s PhD at IMT Mines Alès and the University of Nîmes.

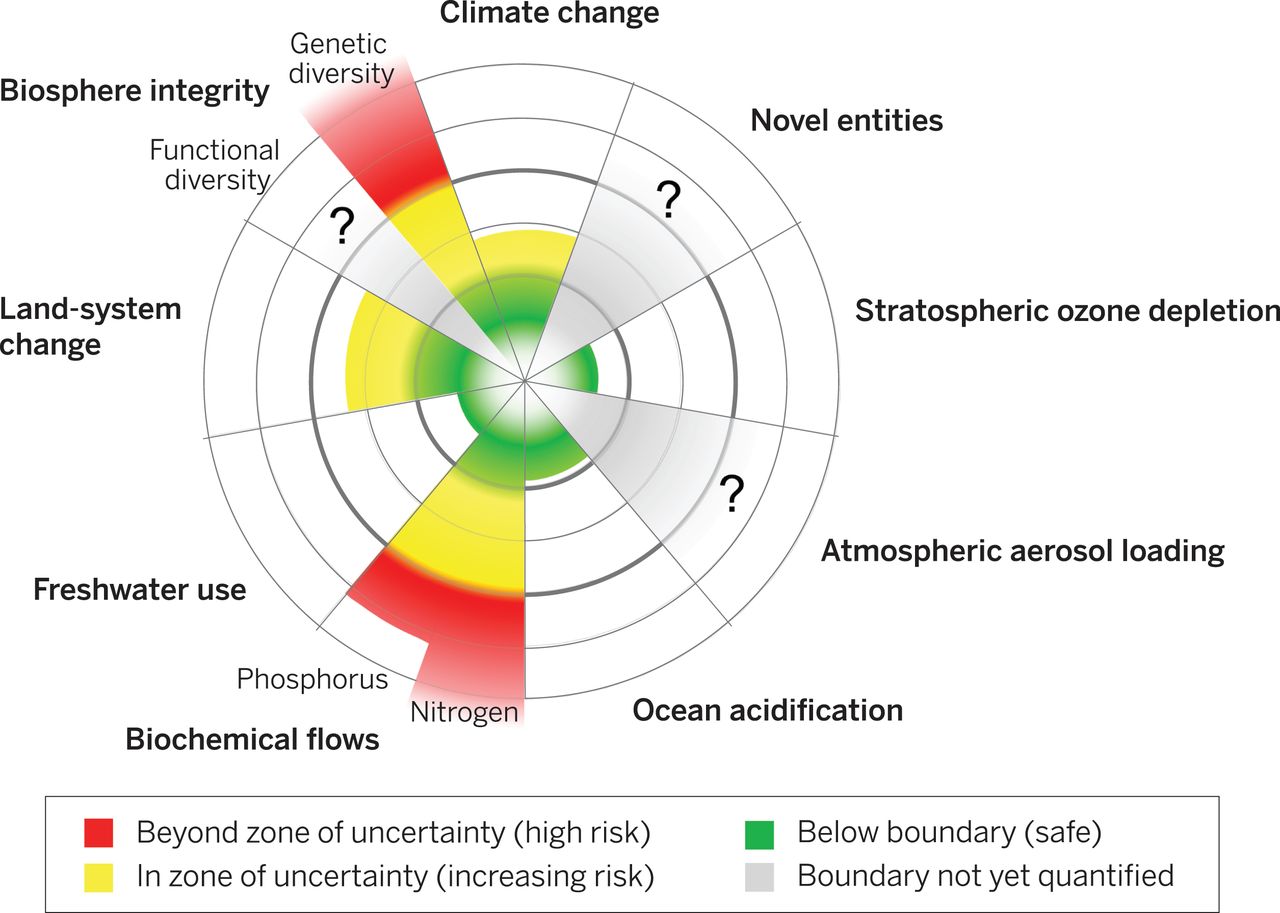

When she began her work in 2018, the Covid-19 crisis and pandemics were not yet a major concern. Exceptional health situations include anything that goes beyond the usual functioning of healthcare services. “We originally had in mind the emergency services being overwhelmed after an attack”, explains Gilles Dusserre, a researcher in risk sciences at IMT Mines Alès and joint supervisor of Marie Bossard with Karine Weiss at the University of Nîmes. Whatever the cause, this research fits into a global reflection on the current problems in emergency medicine. This is what the researchers want to understand better in order to provide operational responses to special users or hospital staff.

The feeling of “preparedness“

“The idea is to start with the individual and study how each person perceives his or her level of preparedness, and then develop these reflections on a collective scale,” says Marie Bossard. The aim is to measure the feeling of “preparedness” and identify the factors that influence it, as well as to apply psychosocial models to the level of preparedness of hospital staff. The PhD student is exploring the social representations of hospital staff through interviews with medical doctors, paramedics, health executives and administrative employees in different French university hospitals.

“We can differentiate the feeling of preparedness, the perception of our preparation, and the reported preparation”, explains Marie Bossard. If hospital staff consider that exceptional health situations are only linked to an attack, for example, they might never be prepared for a fire,” she continues.

And, although the preparation received has an influence on the feeling of preparedness, she insists that “there are many other aspects to take into account. The feeling of self-efficacy is important, in particular.” This psycho-social concept represents, in a way, the power to act: the individual perception of having sufficient skills to manage a situation and knowing how to apply them. The perception of preparation, whether positive or negative, also affects the feeling of preparedness. The role of the collective is also undeniable. “A common response is that, individually, the person doesn’t feel ready, but they still have confidence in the collective, she adds. There’s a certain resignation”, says the joint PhD supervisor. “Hospital systems are already going through a difficult time and are coping, so collectively they feel capable of facing one more challenge.”

In a second phase, the aim is to propose hypotheses on the structure and content of these social representations. For example, health executives do not give the same type of spontaneous responses as paramedics when asked to list words in connection with exceptional health situations. The former generally talk about the practice of preparation (logistics, influx), while the second generally mention everyday examples or emotion (danger, serious, disaster).

The context of the Covid crisis

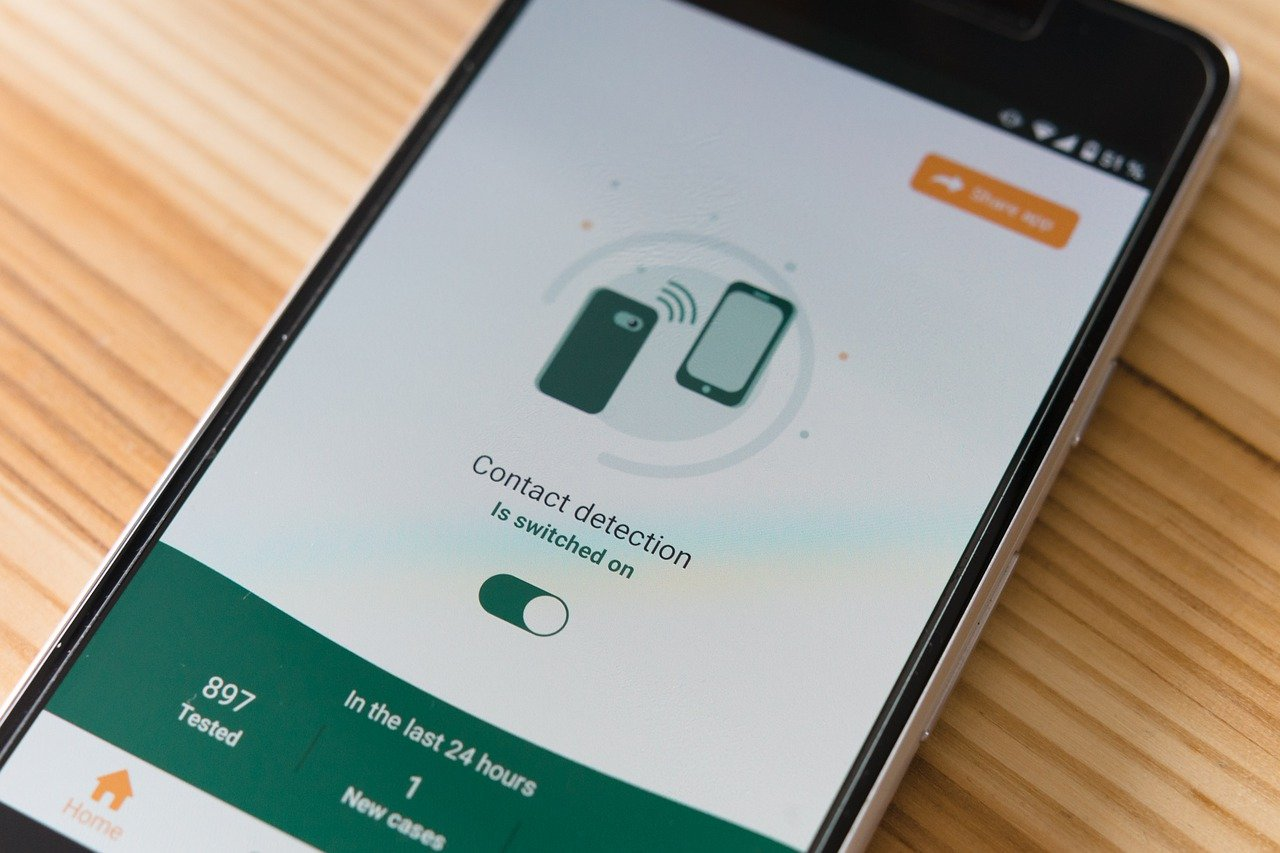

Given that the development of an exceptional health situation was completely unforeseeable, it initially seemed impossible to carry out a field study. However, the pandemic caused by the new coronavirus in early 2020 provided a characteristic field of study for the researchers. Marie Bossard and her joint supervisors reorganized their methodology and two new studies were prepared. The first before the arrival of the virus in France, which studied the preparedness of more than 400 participants among personnel and collectives. The second after the first peak of the epidemic and before a potential second wave, which was still an uncertainty at the time. The questionnaires from the study carried out among 534 participants provide a comparison between the feeling of readiness before and after Covid-19.

The post-Covid study confirmed that the feeling of preparedness depends on psycho-social variables and not just the level of preparation. Age and years of professional experience also influence this feeling, as do the profession and any previous experience of managing an exceptional health situation. These are individual variables, but the role of the collective was also confirmed. “The more ready and prepared others are, the higher the perception of personal preparedness, says Marie Bossard. Similarly, perceiving the hospital as ready, with sufficient human and material resources, has a great influence.” The PhD student is currently studying the results of the latest study conducted in September.

The situation, although difficult, provides “a context for the answers given during the first interviews,” says the PhD student. For example, it confirms that all hospital staff are involved, not just those considered on the front line. Indeed, the mobilization affects every hospital department. She admits that “the Covid-19 health crisis has given us a new perspective on this PhD subject, which is now topical and concretely demonstrates the need for a better understanding in this field“. It is also an opportunity to explore the effect of this exceptional health situation on the feeling of preparedness among those first concerned and the factors that influence this feeling with a concrete application of the subject.

“We haven’t found any previous studies that have explored this subject from the same angle, says Marie Bossard. We’re starting from scratch. The aim is to remain as open-minded as possible to identify initial indicators, and then dig deeper into more specific questions,” she concludes. It could lead to new studies, for example to understand why the feeling of auto-efficacy plays such an important role in the feeling of preparedness.

Tiphaine Claveau