Facebook: a small update causes major disruption

Hervé Debar, Télécom SudParis – Institut Mines-Télécom

Late on October 4, many users of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp were unable to access their accounts. All of these platforms belong to the company Facebook and were all affected by the same type of error: an accidental and erroneous update to the routing information for Facebook’s servers.

The internet employs various different types of technology, two of which were involved in yesterday’s incident: BGP (border gateway protocol) and DNS (domain name system).

In order to communicate, each machine must have an IP address. Online communication involves linking two IP addresses together. The contents of each communication are broken down into packets, which are exchanged by the network between a source and a destination.

How BGP (border gateway protocol) works

The internet is comprised of dozens of “autonomous systems”, or AS, some very large, and others very small. Some AS are interconnected via exchange points, enabling them to exchange data. Each of these systems is comprised of a network of routers, which are connected using either optical or electrical communication links. Communication online circulates using these links, with routers responsible for transferring communications between links in accordance with routing rules. Each AS is connected to at least one other AS, and often several at once.

When a user connects their machine to the internet, they generally do so via an internet service provider or ISP. These ISPs are themselves “autonomous systems”, with address ranges which they allocate to each of their clients’ machines. Each router receiving a packet will analyse both the source and the destination address before deciding to transfer the packet to the next link, following their routing rules.

In order to populate these routing rules, each autonomous system shares information with other autonomous systems describing how to associate a range of addresses in their possession with an autonomous system path. This is done step by step through the use of the BGP or border gateway protocol, ensuring each router has the information it needs to transfer a packet.

DNS (domain name system)

The domain name system was devised in response to concerns surrounding the lack of transparency with IP addresses for end users. For available servers on the internet, this links “facebook.com” with the IP address “157.240.196.35”.

Each holder of a domain name sets up (or delegates) a DNS server, which links domain names to IP addresses. They are considered to be the most reliable source (or authority) for DNS information, but are also often the first cause of an outage – if the machine is unable to resolve a name (i.e. to connect the name requested by the user to an address), then the end user will be sent an error message.

Each major internet operator – not just Facebook, but also Google, Netflix, Orange, OVH, etc. – has one or more autonomous systems and coordinates the respective BGP in conjunction with their peers. They also each have one or more DNS servers, which act as an authority over their domains.

The outage

Towards the end of the morning of October 4, Facebook made a modification to its BGP configuration which it then shared with the autonomous systems it is connected to. This modification resulted in all of the routes leading to Facebook disappearing, across the entire internet.

Ongoing communications with Facebook’s servers were interrupted as a result, as the deletion of the routes spread from one autonomous system to the next, since the routers were no longer able to transfer packets.

The most visible consequence for users was an interruption to the DNS and an error message, followed by the DNS servers of ISPs no longer being able to contact the Facebook authoritative server as a result of the BGP error.

This outage also caused major disruption on Facebook’s end as it rendered remote access and, therefore, teleworking, impossible. Because they had been using the same tools for communication, Facebook employees found themselves unable to communicate with each other, and so repairs had to be carried out at their data centres. With building security also online, access proved more complex than first thought.

Finally, with the domain name “facebook.com” no longer referenced, it was identified as free by a number of specialist sites for the duration of the outage, and was even put up for auction.

Impact on users

Facebook users were unable to access any information for the duration of the outage. Facebook has become vitally important for many communities of users, with both professionals and students using it to communicate via private groups. During the outage, these users were unable to continue working as normal.

Facebook is also an identity provider for many online services, enabling “single sign-on”, which involves users reusing their Facebook accounts in order to access services offered by other platforms. Unable to access Facebook, users were forced to use other login details (which they may have forgotten) in order to gain access.

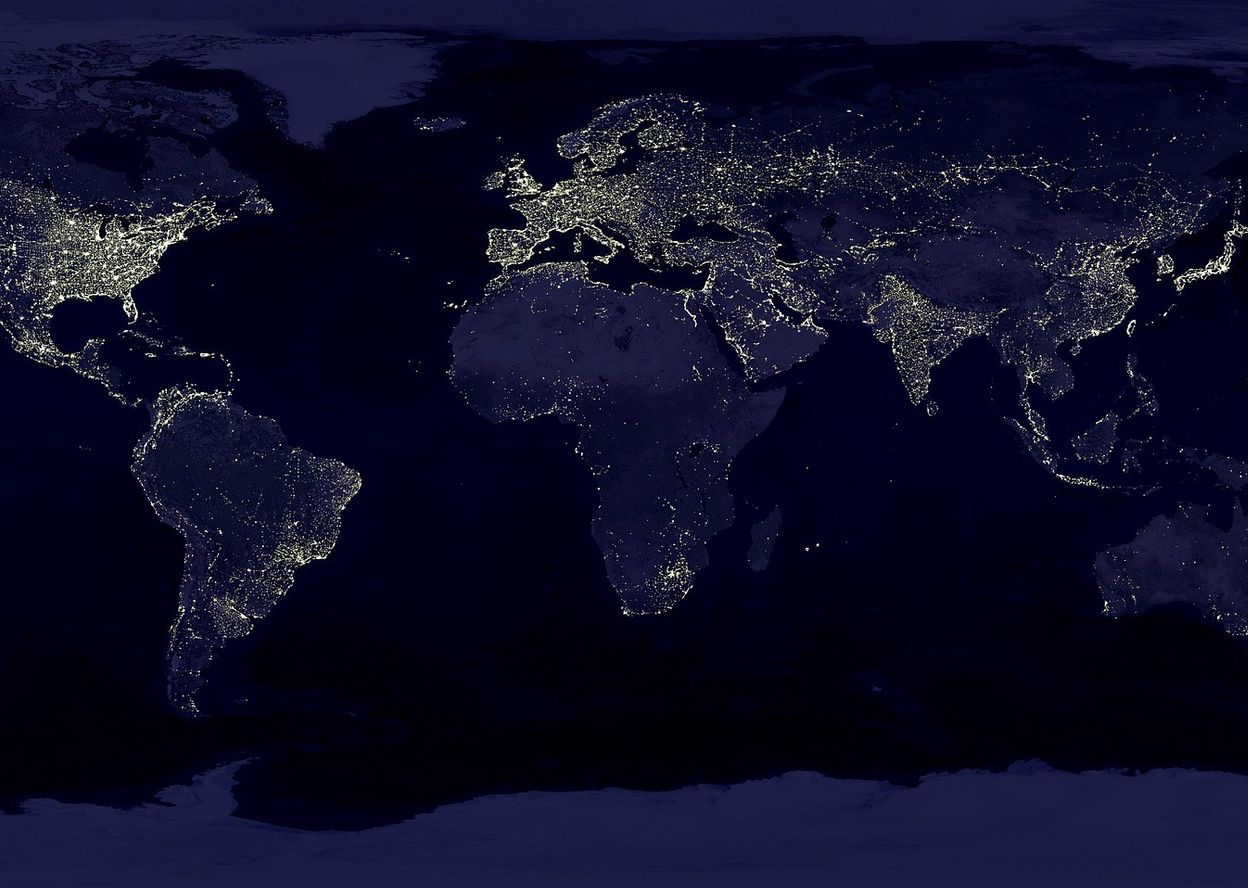

Throughout the outage, users continued to request access to Facebook, leading to an increase in the number of DNS requests made online and a temporary but very much visible overload of DNS activity worldwide.

This outage demonstrated the critical role played by online services in our daily lives, while also illustrating just how fragile these services still are and how difficult it can be to control them. As a consequence, we must now look for these services to be operated with the same level of professionalism and care as other critical services.

Banking, for example, now takes place almost entirely online. A breakdown like the one that affected Facebook is less likely to happen to a bank given the standards and regulations in place for banking, such as the Directive On Network And Service Security, the General Data Protection Regulation or PCI-DSS.

In contrast, Facebook writes its own rules and is partially able to evade regulations such as the GDPR. Introducing service obligations for these major platforms could improve service quality. It is worth pointing out that no bank operates a network as impressive as Facebook’s infrastructure, the size of which exacerbates any operating errors.

More generally, after several years of research and standardisation, safety mechanisms for BGP and DNS are now being deployed, the aim being to prevent attacks which could have a similar impact. The deployment of these security mechanisms will need to be accelerated in order to make the internet more reliable.

Hervé Debar, Director of Research and PhDs, Deputy director, Télécom SudParis – Institut Mines-Télécom

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!