Zero-click attacks: spying in the smartphone era

Zero-click attacks exploit security breaches in smartphones in order to hack into a target’s device without the target having to do anything. They are now a threat to everyone, from governments to medium-sized companies.

“Zero-click attacks are not a new phenomenon”, says Hervé Debar, a researcher in cybersecurity at Télécom SudParis. “In 1988 the first computer worm, named the “Morris worm” after its creator, infected 6,000 computers in the USA (10% of the internet at the time) without any human intervention, causing damage estimated at several million dollars.” By connecting to messenger servers which were open access by necessity, this program exploited weaknesses in server software, infecting it. It could be argued that this was one of the very first zero-click attacks, a type of attack which exploits security breaches in target devices without the victim having to do anything.

There are two reasons why this type of attack is now so easy to carry out on smartphones. Firstly, the protective mechanisms for these devices are not as effective as those on computers. Secondly, more complex processes are required in order to present videos and images, meaning that the codes enabling such content to be displayed are often more complex than those on computers. This makes it easier for attackers to hack in and exploit security breaches in order to spread malware. As Hervé Debar explains, “attackers must, however, know certain information about their target – such as their mobile number or their IP address – in order to identify their phone. This is a targeted type of attack which is difficult to deploy on a larger scale as this would require collecting data on many users.”

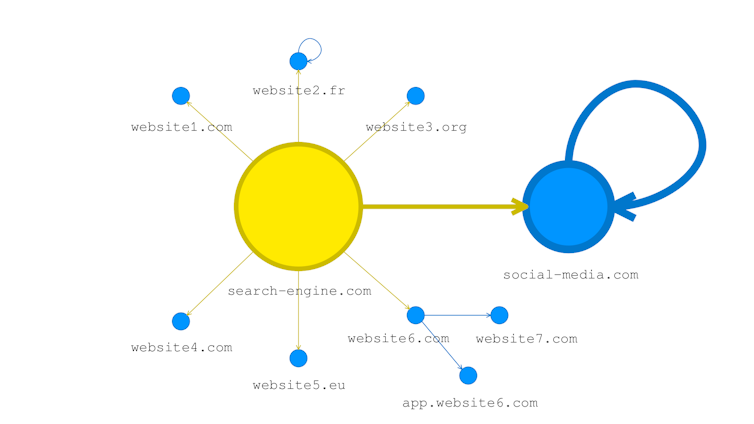

Zero-click attacks tend to follow the same pattern: the attacker sends a message to their target containing specific content which is received in an app. This may be a sound file, an image, a video, a gif or a pdf file containing malware. Once the message has been received, the recipient’s phone processes it using apps to display the content without the user having to click on it. While these applications are running, the attacker exploits breaches in their code in order to run programs resulting in spy software being installed on the target device, without the victim knowing.

Zero-days: vulnerabilities with economic and political impact

Breaches exploited in zero-click attacks are known as “zero-days”, vulnerabilities which are unknown to the manufacturer or which have yet to be corrected. There is now a global market for the detection of these vulnerabilities: the zero-day market, which is made up of companies looking for hackers to identify these breaches. Once the breach has been identified, the hacker will produce a document explaining it in detail, with the company who commissioned the document often paying several thousand dollars to get their hands on it. In some cases the manufacturer themselves might buy such a document in an attempt to rectify the breach. But it may also be bought by another company looking to sell the breach to their clients – often governments – for espionage purposes. According to Hervé Debar, between 100 and 1,000 vulnerabilities are detected on devices each year.

Zero-click attacks are regularly carried out for theft or espionage purposes. For theft, the aim may be to validate a payment made by the victim in order to divert their money. For espionage, the goal might be to recover sensitive data about a specific individual. The most recent example was the Pegasus affair, which affected around 50,000 potential victims, including politicians and media figures. “These attacks may be a way of uncovering secret information about industrial, economic or political projects. Whoever is responsible is able to conceal themselves and to make it difficult to identify the origin of the attack, which is why they’re so dangerous”, stresses Hervé Debar. But it is not only governments and multinationals who are affected by this sort of attack – small and medium-sized companies are too. They are particularly vulnerable in that, owing to a lack of financial resources, they don’t have IT professionals running their systems, unlike major organisations.

Also read on I’MTech Cybersecurity: high costs for companies

More secure computer languages

But there are things that can be done to limit the risk of such attacks affecting you. According to Hervé Debar, “the first thing to do is use your common sense. Too many people fall into the trap of opening suspicious messages.” Personal phones should also be kept separate from work phones, as this prevents attackers from gaining access to all of a victim’s data. Another handy tip is to back up your files onto an external hard drive. “By transferring your data onto an external hard drive, it won’t only be available on the network. In the event of an attack, you will safely be able to recover your data, provided you disconnected the disc after backing up.” To protect against attacks, organisations may also choose to set up intrusion detection systems (IDS) or intrusion prevention systems (IPS) in order to monitor flows of data and access to information.

In the fight against cyber-attacks, researchers have developed alternative computing languages. Ada, a programming language which dates back to the 1980s, is now used in the aeronautic industry, in railways and in aviation safety. For the past ten years or so the computing language Rust has been used to solve problems linked to the management of buffer memory which were often encountered with C and C++, languages widely used in the development of operating systems. “These new languages are better controlled than traditional programming languages. They feature automatic protective mechanisms to prevent errors committed by programmers, eliminating certain breaches and certain types of attack.” However, “writing programs takes time, requiring significant financial investment on the part of companies, which they aren’t always willing to provide. This can result in programming errors leading to breaches which can be exploited by malicious individuals or organisations.”

Rémy Fauvel