Governments, banks, and hospitals: all victims of cyber-attacks

Hervé Debar, Télécom SudParis – Institut Mines-Télécom

Cyber-attacks are not a new phenomenon. The first computer worm distributed via the Internet, known as the “Morris worm” after its creator, infected 10% of the 60,000 computers connected to the Internet at the time.

Published back in 1989, the novel The Cuckoo’s Egg was based on a true story of computer espionage. Since then, there have been any number of malicious events, whose multiple causes have evolved over time. The initial motivation of many hackers was their curiosity about this new technology that was largely out of the reach of ordinary people at the time. This curiosity was replaced by the lure of financial reward, leading firstly to messaging campaigns encouraging people to buy products online, and subsequently followed by denial-of-service attacks.

Over the past few years, there have been three main motivations:

- Direct financial gain, most notably through the use of ransomware, which has claimed many victims.

- Espionage and information-gathering, mostly state-sponsored, but also in the private sphere.

- Data collection and manipulation (normally personal data) for propaganda or control purposes.

These motivations have been associated with two types of attack: targeted attacks, where hackers select their targets and find ways to penetrate their systems, and large-scale attacks, where the attacker’s aim is to claim as many victims as possible over an extended period of time, as their gains are directly proportional to their number of victims.

The era of ransomware

Ransomware is a type of malware which gains access to a victim’s computer through a back door before encrypting their files. A message is then displayed demanding a ransom in exchange for decrypting these files.

Kaseya cash register software

In July 2021, an attack was launched against Kaseya cash register software, which is used by several store chains. It affected the Cloud part of the service and shut down the payment systems of several retail chains.

The Colonial Pipeline attack

One recent example is the attack on the Colonial Pipeline, an oil pipeline which supplies the eastern United States. The attack took down the software used to control the flow of oil through the pipeline, leading to fuel shortages at petrol stations and airports.

This is a striking example because it affected a visible infrastructure and had a significant economic impact. However, other infrastructure – in banks, factories, and hospitals – regularly fall victim to this phenomenon. It should also be noted that these attacks are very often destructive, and that paying the ransom is not always sufficient to guarantee the recovery of one’s files.

Unfortunately, such attacks look set to continue, at least in the short-term, given the financial rewards for the perpetrators: some victims pay the ransom despite the legal and ethical questions this raises. Insurance mechanisms protecting against cyber-crime may have a detrimental effect, as the payment of ransoms only encourages hackers to continue. Governments have also introduced controls on cryptocurrencies, which are often used to pay these ransoms, in order to make payments more difficult. Paradoxically, however, payments made using cryptocurrency can be traced in a way that would be impossible with traditional methods of payment. We can therefore hope that this type of attack will become less profitable and riskier for hackers, leading to a reduction in this type of phenomenon.

Targeted, state-sponsored attacks

Infrastructure, including sovereign infrastructure (economy, finance, justice, etc.), is frequently controlled by digital systems. As a result, we have seen the development of new practices, sponsored either by governments or extremely powerful players, which implement sophisticated methods over an extended time frame in order to attain their objectives. Documented examples include the Stuxnet/Flame attack on Iran’s nuclear program, and the SolarWinds software hack.

SolarWinds

The attack targeting Orion and its SolarWinds software is a textbook example of the degree of complexity that can be employed by certain perpetrators during an attack. As a network management tool, SolarWinds plays a pivotal role in the running of computer systems and is used by many major companies as well as the American government.

The initial attack took place between January and September of 2019, targeting the SolarWinds compilation environment. Between the fall of 2019 and February 2020, the attacker interacted with this environment, embedding additional features. In February 2020, this interaction enabled the introduction of a Trojan horse called “Sunburst”, which was subsequently incorporated into SolarWinds’ updates. In this way, it became embedded in all of Orion’s clients’ systems, infecting as many as 18,000 organizations. The exploitation phase began in late 2020 when further malicious codes downloaded by Sunburst were injected, and the hacker eventually managed to breach the Office365 cloud used by the compromised companies. Malicious activity was first detected in December 2020, with the theft of software tools from the company FireEye.

This has continued throughout 2021 and has had significant impacts, underlining both the complexity and the longevity of certain types of attack. American intelligence agencies believe this attack to be the work of SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence service, which has denied this accusation. It is likely that the strategic importance of certain targets will lead to future developments of this type of deep, targeted attack. The vital role played by digital tools in the running of our critical infrastructure will doubtless encourage states to develop cyber weapons, a phenomenon that is likely to increase in the coming years.

Social control

Revelations surrounding the Pegasus software developed by NSO have shown that certain countries can benefit significantly from compromising their adversaries’ IT equipment (including smartphones).

The example of Tetris

Tetris is the name given to a tool used (potentially by the Chinese government) to infiltrate online chat rooms and reveal the identities of possible opponents. This tool has been used on 58 sites and uses relatively complex methods to steal visitors’ identities.

“Zero-click” attacks

The Pegasus revelations shed light on what are known as “zero-click” attacks. Many attacks on messaging clients or browsers assume that an attacker will click a link, and that this click will then cause the victim to be infected. With zero-click attacks, targets are infected without any activity on their part. One ongoing example of this hack is the ForcedEntry or CVE-2021-30860 vulnerability, which has affected the iMessage app on iPhones.

Like many others, this application accepts data in a wide range of formats and must carry out a range of complex operations in order to present it to users in an elegant way, despite its reduced display format. This complexity has extended the opportunities for attacks. An attacker who knows a victim’s phone number can send them a malicious message, which will trigger an infection as it is processed by the phone. Certain vulnerabilities even make it possible to delete any traces (at least visible traces) that the message was received, in order to avoid alerting the target.

Despite the efforts to make IT platforms harder to hack, it is likely that certain states and private companies will remain capable of hacking into IT systems and connected objects, either directly (via smartphones, for example) or via the cloud services to which they are connected (e.g. voice assistants). This takes us into the world of politics, and indeed geopolitics.

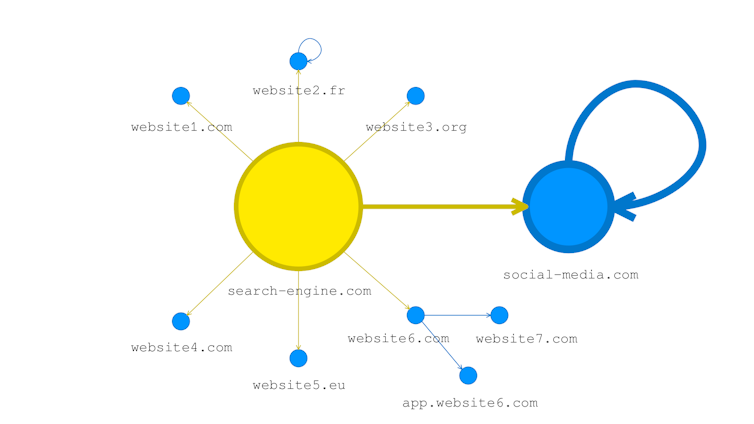

The biggest problem with cyber-attacks remains identifying the origin of the attack and who was behind it. This is made even more difficult by attackers trying to cover their tracks, which the Internet gives them multiple opportunities to do.

How can you prevent an attack?

The best way of preventing an attack is to install the latest updates for systems and applications, and perhaps ensure that they are installed automatically. The majority of computers, phones and tablets can be updated on a monthly basis, or perhaps even more frequently. Another way is to activate existing means of protection such as firewalls or anti-virus software, which will eliminate most threats.

Saving your work on a regular basis is essential, whether onto a hard drive or in the Cloud, as is disconnecting from these back-ups once they have been completed. Back-up copies are only useful if they are kept separate from your computer, otherwise ransomware will attack your back-up drive as well as your main drive. Backing up twice, or saving key information such as the passwords to your main applications (messenger accounts, online banking, etc.) in paper form, is another must.

Digital tools should also be used with caution. Follow this simple rule of thumb: if it seems too good to be true in the real world, then there is every chance that it is also the case in the virtual world. By paying attention to any messages that appear on our screens and looking out for spelling mistakes or odd turns of phrase, we can often identify unusual behavior on the part of our computers and tablets and check their status.

Lastly, users must be aware that certain activities are risky. Unofficial app stores or downloads of executables in order to obtain software without a license often contain malware. VPNs, which are widely used to watch channels from other regions, are also popular attack vectors.

What should you do if your data is compromised?

Being compromised or hacked is highly stressful, and hackers constantly try to make their victims feel even more stressed by putting pressure on them or by sending them alarming messages. It is crucial to keep a cool head and find a second device, such as a computer or a phone, which you can use to find a tool that will enable you to work on the compromised machine.

It is essential to return to a situation in which the compromised machine is healthy again. This means a full system recovery, without trying to retrieve anything from the previous installation in order to prevent the risk of reinfection. Before recovery, you must analyze your back-up to make that sure no malicious code has been transferred to it. This makes it useful to know where the infection came from in the first place.

Unfortunately, the loss of a few hours of work has to be accepted, and you simply have to find the quickest and safest way of getting up and running again. Paying a ransom is often pointless, given that many ransomware programs are incapable of decrypting files. When decryption is possible, you can often find a free program to do it, provided by security software developers. This teaches us to back up our work more frequently and more extensively.

Finally, if you lack in-house cybersecurity expertise, it is highly beneficial to obtain assistance with the development of an approach that includes risk analyses, the implementation of protective mechanisms, the exclusive use of certified cloud services, and the performance of regular audits carried out by certified professionals capable of detecting and handling cybersecurity incidents.

Hervé Debar, Director of Research and PhDs, Deputy Director of Télécom SudParis.

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article (in French).