Crisis management: better integration of citizens’ initiatives

Caroline Rizza, Télécom Paris – Institut Mines-Télécom

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s part of my research into the benefits of digital technologies in crisis management and in particular the digital skills of those involved in a crisis (whether institutions or grassroots citizens), I had the opportunity to shadow the Fire and Emergency Department of the Gard (SDIS) in Nîmes, from 9 to 23 April 2020, during the COVID-19 health crisis.

This immersive investigation enabled me to fine-tune my research hypotheses on the key role of grassroots initiatives in crises, regardless of whether they emerge in the common or virtual public space.

Social media to allow immediate action by the public

So called “civil security” crises are often characterized by their rapidity (a sudden rise to a “peak”, followed by a return to “normality”), uncertainties, tensions, victims, witnesses, etc.

The scientific literature in the field has demonstrated that grassroots initiatives appear at the same time as the crisis in order to respond to it: during an earthquake or flood, members of the public who are present on-site are often the first to help the victims, and after the crisis, local people are often the ones who organize the cleaning and rebuilding of the affected area. During the Nice terror attacks of July 2016, for example, taxi-drivers responded immediately by helping to evacuate the people present on the Promenade des Anglais. A few months earlier, during the Bataclan attacks in 2015, Parisians opened their doors to those who could not go home and used the hashtag #parisportesouvertes (parisopendoors). Genoa experienced two rapid and violent floods in 1976 and 2011; on both occasions, young people volunteered to clean up the streets and help shop owners and inhabitants in the days that followed the event.

There has been an increase in these initiatives, following the arrival of social media in our daily lives, which has helped them emerge and get organized online as a complement to actions that usually arise spontaneously on the field.

My research lies within the field of “crisis informatics”. I am interested in these grassroots initiatives which emerge and are organized through social media, as well as the issues surrounding their integration into crisis management. How can we describe these initiatives? What mechanisms are they driven by? How does their creation change crisis management? Why should we integrate them into crisis response?

Social media as an infrastructure for communication and organization

Since 2018, I have been coordinating the ANR MACIV project (Citizen and volunteer management: the role of social media in crisis scenarios). We have been looking at all the aspects of social media in crisis management: the technological aspect with the tools which can automatically supply the necessary information to institutional players; the institutional aspect of the status of the information coming from social media and its use in the field; the grassroots aspect, linked to the mechanisms involved in the creation and sharing of the information on social media and the integration of grassroots initiatives into the response to the crisis.

We usually think of social media as a means of communication used by institutions (ministries, prefectures, municipalities, fire and emergency services) to communicate with citizens top-down and improve the situational analysis of the event through the information conveyed bottom-up from citizens.

The academic literature in the field of “crisis informatics” has demonstrated the changes brought by social media, and how citizens have used them to communicate in the course of an event, provide information or organize to help.

On-line and off-line volunteers

We generally distinguish between “volunteers” in the field and online. As illustrated above, volunteers who are witnesses or victims of an event are often the first to intervene spontaneously, while social media focuses on organizing online help. This distinction can help us understand how social media have become a means of expressing and organizing solidarity.

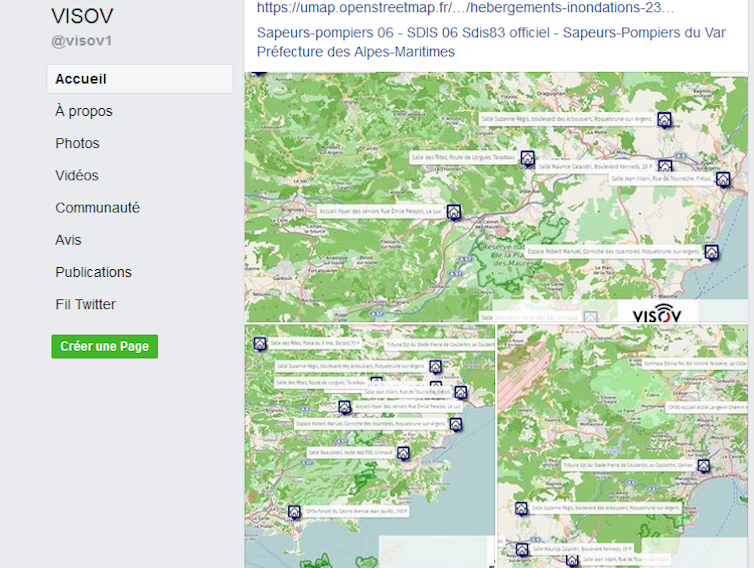

It is interesting to note that certain groups of online volunteers are connected through agreements with public institutions and their actions are coordinated during an event. In France, VISOV (international volunteers for virtual operation support) is the French version of the European VOST (Virtual Operations Support Team); but we can also mention other groups such as the WAZE community.

Inform and organize

There is therefore an informational dimension and an organizational dimension to the contribution of social media to crisis management.

Informational in that the content that is published constitutes a source of relevant information to assess what is happening on site: for example, fire officers can use online social media, photos and videos during a fire outbreak, to readjust the means they need to deploy.

And organizational in that aim is to work together to respond to the crisis.

For example, creating a Wikipedia page about an ongoing event (and clearing up uncertainties), communicating pending an institutional response (Hurricane Irma, Cuba, in 2017), helping to evacuate a place (Gard, July 2019), taking in victims (Paris, 2015; Var, November 2019), or helping to rebuild or to clean a city (Genoa, November 2011).

Screenshot of the Facebook page of VISOV to inform citizens of available accommodation following the evacuation of certain areas in the Var in December 2019. VISOV Facebook page

An increased level of organization

During my immersion within the SDIS of the Gard as part of the management of the COVID-19 crisis, I had the chance to discuss and observe the way in which social media were used to communicate with the public (reminding them of preventative measures and giving them daily updates from regional health agencies), as well as to integrate some grassroots initiatives.

Although the crisis was a health crisis, it was also one of logistics. Many citizens (individuals, businesses, associations, etc.) organized to support the institutions: sewing masks or making them with 3D printers, turning soap production into hand sanitizer production, proposing to translate information on preventative measures into different languages and sharing it to reach as many citizens as possible; these were all initiatives which I came across and which helped institutions organize during the peak of the crisis.

Example of protective visors made using 3D printers for the SDIS 30.

The “tunnel effect”

However, the institutional actors I met and interviewed within the framework of the two studies mentioned above (SDIS, Prefecture, Defense and Security Zone, DGSCGC) all highlighted the difficulty of taking account of information shared on social media – and grassroots initiatives – during crises.

The large number of calls surrounding the same event, the excess information to be dealt with and the gravity of the situation mean that the focus has to be on the essentials. These are all examples of the “tunnel effect”, identified by these institutions as one of the main reasons for the difficulty of integrating these tools into their work and these actions into their emergency response.

The information and citizen initiatives which circulate on social media simultaneously to the event may therefore help the process of crisis management and response, but paradoxically, they can also make it more difficult.

Then there is also the sharing through social media of rumors and fake news, especially when there is a gap in the information or contradictory ideas linked to an event (go to page Wikipedia during the COVID-19 crisis).

How and why should we encourage this integration?

Citizen initiatives have impacted institutions horizontally in their professional practices.

My observation of the management of the crisis within the SDIS 30 enabled me to go one step further and put forward the hypothesis that another dimension is slowing down the integration of these initiatives which emerge in the common or virtual public space: it implies placing the public on the same level as the institution; in other words, these initiatives do not just have an “impact” horizontally on professional practices and their rules (doctrines), but this integration requires the citizen to be recognized as a participant in the management and the response to the crisis.

There is still a prevailing idea that the public needs to be protected, but the current crisis shows that the public also want to play an active role in protecting themselves and others.

The main question that then arises is that of the necessary conditions for this recognition of citizens as participants in the management and response to the crisis.

Relying on proximity

It is interesting to note that at a very local level, the integration of the public has not raised problems and on the contrary it is a good opportunity to diversify initiatives and recognize each of the participants within the region.

However, at a higher level in the operational chain of management, this poses more problems because of the commitment and responsibility of institutions in this recognition.

My second hypothesis is therefore as follows: the close relations between stakeholders within the same territorial fabric allow better familiarity with grassroots players, thereby fostering mutual trust – this trust seems to me to be the key to success and explains the successful integration of grassroots initiatives in a crisis, as illustrated by the VISOV or VOST.

[divider style=”dotted” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

The original version of this article (in French) was published on The Conversation.

By Caroline Rizza, researcher in information sciences at Télécom Paris.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!