This article originally appeared (in French) in newsletter no. 17 of the VP-IP Chair, Data, Identity, Trust in the Digital Age for April 2020.

[divider style=”dotted” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

The current pandemic and unprecedented measures taken to slow its spread provide an opportunity to measure and assess the impact of digital technology on our societies, including in terms of its legal and ethical contradictions.

While the potential it provides, even amid a major crisis, is indisputable, the risks of infringements on our fundamental freedoms are even more evident.

Without giving in to a simplistic but unrealistic ad hoc techno-solutionism, it would seem appropriate to observe the current situation by looking back forty years into the past, at a time when there was no internet or digital technology at our sides to soften the shock and provide a rapid global response.

The key role of digital technology during the health crisis

Whether to continue economic activity with remote work and remote conferences or to stay in touch with family and friends, digital technology, in its diverse uses, has proved to be invaluable in these exceptional times.

Without such technology, the situation would clearly have been much worse, and the way of life imposed upon us by the lockdown even harder to bear. It also would have been much more difficult to ensure outpatient care and impossible to provide continued learning at home for primary, secondary and higher education students.

The networks and opportunities for remote communication it provides and the knowledge it makes available are crucial assets when it comes to structuring our new reality, in comparison to past decades and centuries.

This health crisis requires an urgent response and therefore serves a brutal reminder of the importance of research in today’s societies, marked by the appearance of novel, unforeseeable events, in a time of unprecedented globalization and movement of people.

Calls for projects launched in France and Europe – whether for research on testing, immunity, treatments for the virus and vaccines that could be developed – also include computer science and humanities components. Examples include aspects related to mapping the progression of the epidemic, factors that can improve how health care is organized and ways to handle extreme situations.

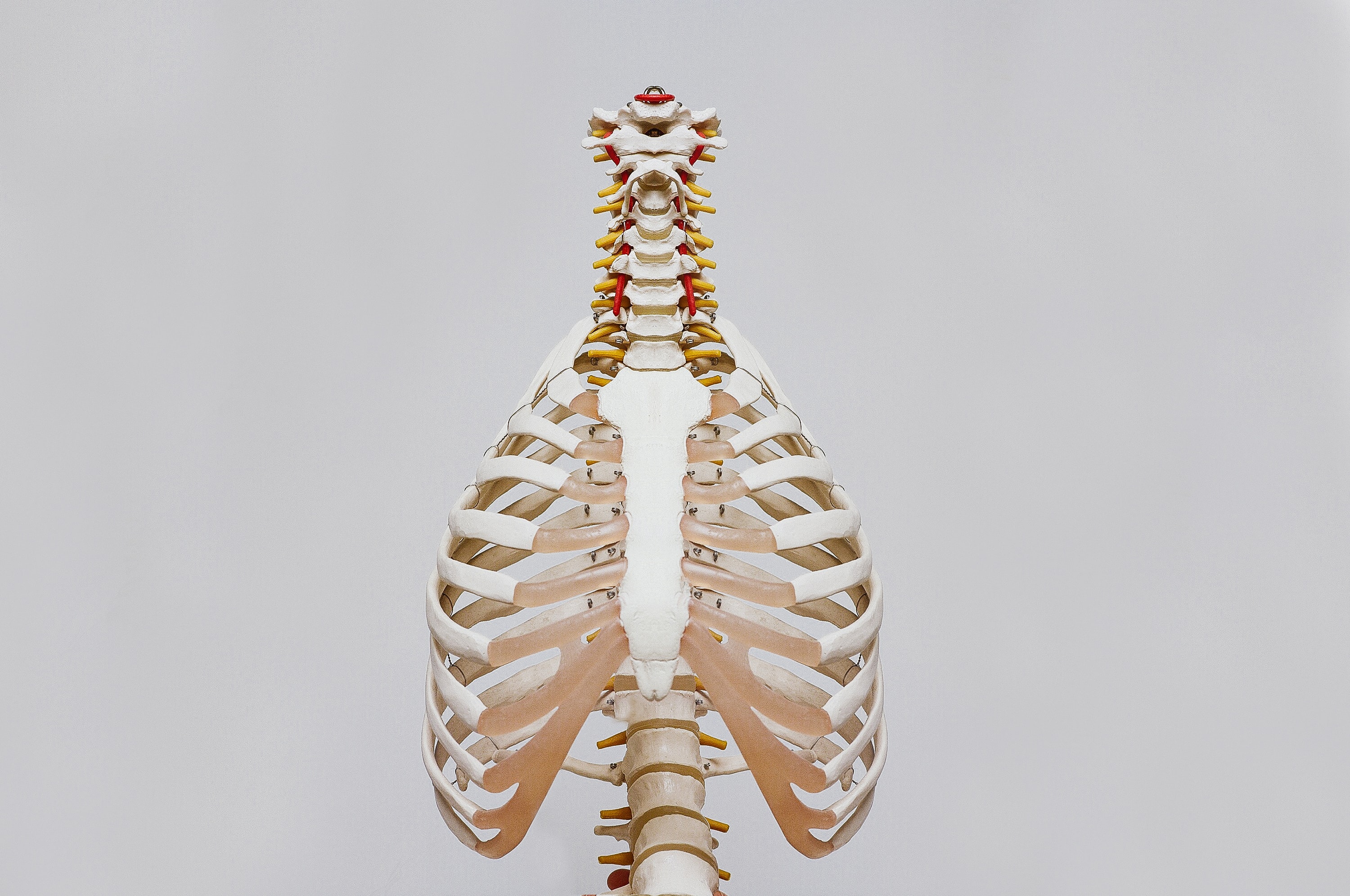

Digital technology has enabled all of the researchers involved in these projects to continue working together, thinking collectively and at a fast pace. And through telemedicine (even in its early stages), it has provided a way to better manage, or at least significantly absorb, the current crisis and its associated developments.

In economic terms, although large swaths of the economy are in tatters and the country’s dependence on imports has made certain situations especially strained – as illustrated by the shortage of protective masks, a topic that has received wide media coverage – other sectors, far from facing a crisis, have seen a rise in demand for their products or services. This has been the case for companies in the telecommunications sector and related fields like e-commerce.

Risks related to personal data

While the crisis has led to a sharp rise in the use of digital technology, the present circumstances also present clear risks as far as personal data is concerned.

Never before has there been such a constant flow of data, since almost all the information involved in remote work is stored on company servers and passed through third party interfaces from employees’ homes. And never before has so much data about our social lives, family and friends been made available to internet and telecommunications companies since – with the exception of those with whom we are spending the lockdown period – more than ever, all of our communication depends on networks.

This underscores the potential offered by the dissemination and handling of the personal data that is now being generated and processed, and consequently, the potential danger, at both the individual and collective level, should it be used in a way that does not respect the basic principles governing data processing.

Yet, adequate safeguards are not yet in place, since the social contract relating to this area is still being developed and debated.

Companies that do not comply with the GDPR have not changed their practices [1] and the massive use of new forms of online connection continue to create risks, given the sensitive nature of the data that may be or is collected.

Examples include debates about the data protection policy for medical consultation interfaces and issuing prescriptions online [2]; emergency measures to enable distance learning via platforms whose data protection policies have been criticized or are downright questionable (Collaborate or Discord, which has been called “spyware” by some [3] to name just a few of many examples); the increased use of video conferencing, for which some platforms do not offer sufficient safeguards in terms of personal data protection, or which have received harsh criticism following an examination of their capacity for cybersecurity and for protecting the privacy of the information exchanged.

For Zoom, notably, which is very popular at the moment, it has reportedly been “revealed that the company shared information about some of its users with Facebook and could discreetly find users’ LinkedIn profiles without their knowledge” [4].

There are also more overall risks, relating to how geolocation could be used, for example. The CNIL (the French Data Protection Authority) [5], the European Data Protection Committee [6] and the European Data Protection Supervisor [7] have given precise opinions on this matter and their advice is being sought at the moment.

In general, mobile tracking applications, such as the StopCovid application being studied by the government [8], and the issue of aggregation of personal data require special attention. This topic has been widely covered by the French [9], European [10] and international [11] media. The CNIL has called for vigilance in this area and has published recommendations [12].

The present circumstances are exceptional and call for exceptional measures – but these measures must only infringe on our freedom of movement, right to privacy and personal data protection rights with due respect for our fundamental principles: necessity of the measure, proportionality, transparency, and loyalty, to name just a few.

The least intrusive solutions possible must be used. In this respect, Ms Marie-Laure Denis, President of the CNIL, explains, “Proportionality may also be assessed with regard to the temporary nature, related solely to the management of the crisis, of any measure considered” [13].

The exceptional measures must not last beyond these exceptional circumstances. They must not be left in place for the long term and chip away at our fundamental rights and freedoms. We must be particularly vigilant in this area, as the precedent for measures adopted for a transitional period in order to respond to exceptional circumstances (the Patriot Act in the United States, the state of emergency in France) has unfortunately shown that these measures have been continued – with doubts as to their necessity – and some have been established in ordinary law provisions and have therefore become part of our daily lives [14].

[divider style=”dotted” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

Claire Levallois-Barth, Lecturer in Law at Télécom Paris, Coordinator of the VP-IP Chair (Personal Information Values and Policies)

Maryline Laurent, Computer Science Professor at Télécom SudParis and Co-Founder of the VP-IP Chair

Ivan Meseguer, European Affairs, Institut Mines-Télécom, Co-Founder of the VP-IP Chair

Patrick Waelbroeck, Professor of Industrial Economics and Econometrics at Télécom Paris, Co-Founder of the VP-IP Chair

Valérie Charolles, Philosophy Researcher at Institut Mines-Télécom Business School, member of the VP-IP Chair, Associate Researcher at the Interdisciplinary Institute of Contemporary Anthropology (EHESS/CNRS)