When microorganisms attack or repair materials

Some microorganisms can seriously damage structures made of concrete or stone, leading to billions of euros in damage. Others, on the contrary, have a positive effect as they are able to heal micro-cracks.

They are microscopic, but can cause billions of euros in damage. Microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi and algae, are ubiquitous in the environment and can develop under some conditions on the surface of buildings and structures. Their impacts should not be neglected. Facades, water treatment plants and sewer pipes must all be monitored, repaired and better designed to withstand these attacks.

Costly deterioration

“Microorganisms form biofilms that adhere to the surface of materials and interact with them. In certain cases, they deteriorate the materials,” explains Christine Lors, professor at the Center for Educating, Research and Innovation (CERI) in Materials and Processes at IMT Lille Douai. “This causes several billions of euros of damage, particularly for sewage systems.” Indeed, most of the large-diameter pipes that carry our wastewater to treatment plants are made of concrete, and their premature deterioration is very costly. Microorganisms develop on the surface of concrete as well as on the stones of buildings, such as churches. This does not always endanger the monuments but can generate significant costs in cleaning the biological fouling, as in the case of facings. They can also affect health in the indoor environments of buildings, through the proliferation of fungi, which can lead to pathologies for occupants.

In general, microorganisms do not directly deteriorate the structures. They produce molecules through their metabolism that alter the materials. For example, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria derive their energy from sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide with its rotten-egg odor present in wastewater. They transform it into sulfuric acid, which is very aggressive for concrete. Nitrifying bacteria found in wastewater treatment plants, on the other hand, produce nitric acid from nitrogen pollution. Finally, in the biomethanation plants, which operate in the absence of oxygen, the acidogenic bacteria produce organic acids, such as acetic, propionic and butyric acids.

Solutions exist

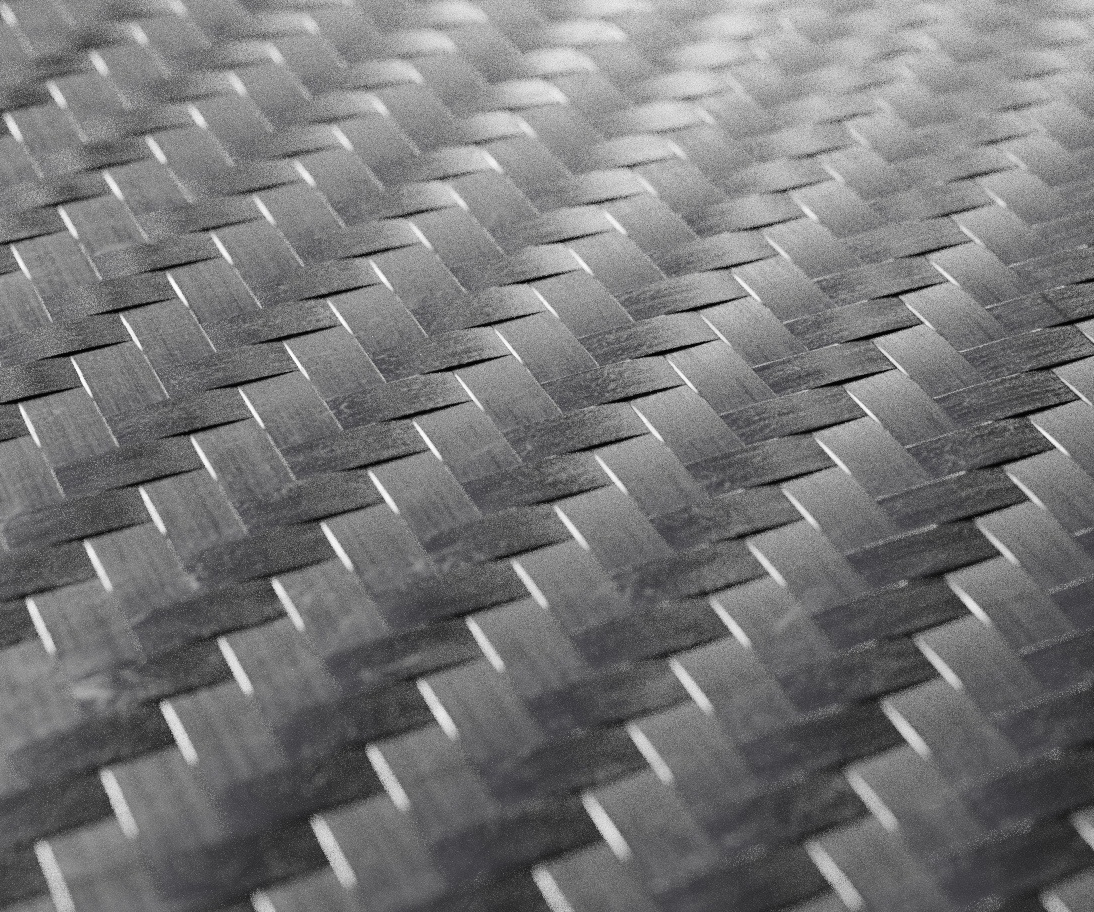

How to prevent or at least limit biodeterioration? First of all, by working on the surface of the materials to reduce the adhesion of the biofilm. The rougher the surface, the easier it is for microorganisms to adhere to it, finding in each roughness an anchor point. The material’s surface tension also plays a role in the adhesion of the biofilm.

The other means of fighting biodeterioration is changing the material itself. Some cements resist better because they neutralize the acid produced without rapidly decreasing their own pH, thus preventing, as in the case of sewage systems, the development of the most acidophilic species. Another important factor to consider is that unaltered concrete is highly basic and very few microorganisms can develop on it. A concrete designed so that its surface pH decreases weakly limits the colonization of its surface.

Finally, for existing structures that tend to deteriorate, it is possible to add a layer of high-strength fiber-reinforced concrete that protects the underlying initial concrete. This addition is costly, but not as expensive as replacing the entire material for large-diameter pipes and sewage collectors.

Useful microorganisms

So far, this depiction of microorganisms has painted them as a scourge to be systematically eradicated from all structures. However, in certain cases, they are actually beneficial. “Some bacteria have a positive effect, by depositing calcium carbonate (limestone) on the material’s surface, they protect them and fill in micro-cracks,” Christine Lors explains. “This is the case for bacteria of the Bacillus genus, which, when breathing, produces carbon dioxide, which combines with calcium to form calcium carbonate.” This phenomenon is of great interest to EDF, which collaborates with the Materials and Processes CERI on the issue of repairing micro-cracks in nuclear enclosures. The goal: to develop a bioprecipitation process to repair these micro-cracks, especially in inaccessible areas.

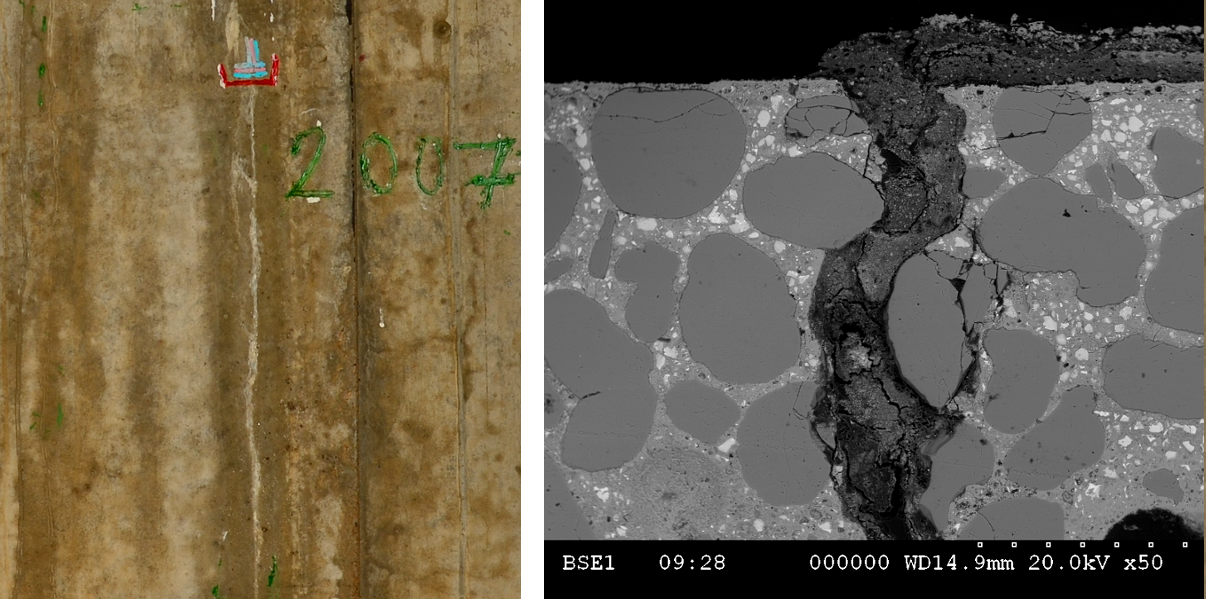

Microorganisms can heal cracks in a wall. The bioprecipitated white calcium carbonate that seals the crack appearing as a white line (left side). A scanning electron microscopy image (right side) shows the filling phenomenon.

“We began by developing laboratory tests to understand the bioprecipitation mechanisms”, the researcher explains. “This required understanding under which conditions the calcium carbonate producing bacteria adhere to the micro-cracked material and then fills in the micro-crack. Then, we have developed a process to control the growth of these bacteria by optimizing their potential to produce calcium carbonate according to many parameters (temperature, nutrients, oxygenation, etc.). Finally, we conducted tests on a model from EDF that reproduces at 1/3 scale a nuclear reactor enclosure. The initial tests are promising: the micro-cracks are clogged and resist the application of a pressure of 5 bars corresponding to the decennial pressurization tests.”

Bioprecipitation process to repair nuclear enclosures

The current bacterial strain capable of healing micro-cracks comes from a laboratory collection. In the future, the objective is to use indigenous strains taken from the nuclear site, previously identified, and whose potential for production of calcium carbonate is verified. These indigenous strains are indeed better adapted to the environmental conditions of the site. When will this technique be applicable under real conditions in nuclear enclosures? “We are currently checking the feasibility, through a PhD thesis underway on this topic that is co-funded with EDF,” Christine Lors explains. “This method could be operational by the end of the PhD thesis.” The Materials and Processes CERI is also planning to create a start-up to develop this process.

Regardless of whether their effects are negative or positive, interactions between microorganisms and civil engineering materials must be taken into account more effectively. This is a standardization issue. “The current standards for structures incorporate both mechanical and chemical aspects, but the impact of microorganisms is by no means taken into account,” Christine Lors explains. “This should be done at the European level, with standardized tests. This is one of the conditions required in order for manufacturers to test their products and conduct research to improve them by taking into account biological alteration.” Thus, there is a big wait for standardization organizations.

Article written (in French) by Cécile Michaut, for I’MTech

Also read on I’MTech