Ioan-Mihai Miron: Magnetism and Memory

Ioan Mihai Miron’s research in spintronics focuses on new magnetic systems for storing information. The research carried out at Spintec laboratory in Grenoble is still young, having begun in 2011. However, it already represents major potential in addressing the current limits facing technology in terms of our computers’ memory. The research also offers a solution to problems experienced by magnetic memories until now, which have prevented their industrial development. Ioan-Mihai Miron received the 2018 IMT-Académie des sciences Young Scientist Award for his groundbreaking and promising research.

Ioan-Mihai Miron’s research is a matter of memory… and a little architecture too. When presenting his work on the design of new nanostructures for storing information, the researcher from Spintec* uses a three-level pyramid diagram. The base represents broad and robust mass memory. Its large size enables it to store large amounts of information, but it is difficult to access. The second level is the central memory, which is not as big but faster to access. It includes the information required to launch programs. Finally, the top of the pyramid is cache memory, which is much smaller but more easily accessible. “The processor only works with this cache memory,” the researcher explains. “The rest of the computer system is there to retrieve information lower down in the pyramid as fast as possible and bring it up to the top.”

Of course, computers do not actually contain pyramids. In microelectronics, this memory architecture takes the form of thousands of microscopic transistors that are responsible for the central and cache memories. They work as switches, storing the information in binary format and either letting the current circulate or blocking it. With the commercial demand for miniaturization, transistors have gradually reached their limit. “The smaller the transistor, the greater the stand-by consumption,” Ioan-Mihai Miron explains. This is why the goal is now for the types of memory located at the top of the pyramid to rely on new technologies based on storing information at the electronic level. By modifying the current sent into magnetic material, the magnetization can be altered at certain points. “The material’s electrical resistance will be different based on this magnetization, meaning information is being stored,” Ioan-Mihai Miron explains. In simpler terms, a high electrical resistance corresponds to one value, a low resistance to another, which forms a binary system.

In practical terms, information is written in these magnetic materials by sending two perpendicular currents, one from above and one from below the material. The point of intersection is where the magnetization is modified. While this principle is not new, it still is not currently used for cache memory in commercial products. Pairing magnetic technologies with this type of data storage has remained a major industrial challenge for almost 20 years. “Memory capacities are still too low in comparison with transistors, and miniaturizing the system is complicated,” the researcher explains. These two disadvantages are not offset by the energy savings that the technology offers.

To compensate for these limitations, the scientific community has developed a simplified geometry of these magnetic architectures. “Rather than intersecting two currents, a new approach has been to only send a single linear path of current into the material,” Ioan-Mihai Miron explains. “But while this technique solved the miniaturization and memory capacity problems, it created others.” In particular, writing the information involves applying a strong electric current that could damage the element where the information is stored. “As a result, the writing speed is not sufficient. At 5 nanoseconds, it is slower than the latest generations of transistor-based memory technology.”

Electrical geometry

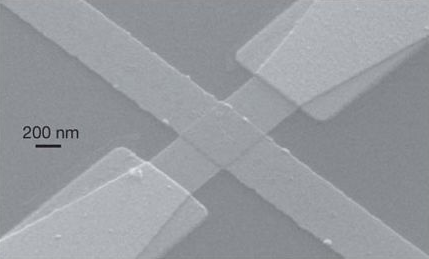

In the early 2010s, Ioan-Mihai Miron’s research opened major prospects for solving all these problems. By slightly modifying the geometry of the magnetic structures, he demonstrated the possibility of writing at speeds in under a nanosecond. And the same size offers a greater memory capacity. The principle is based on the use of a current sent into a plane that is parallel to the layers of the magnetized material, whereas previously the current had been perpendicular. This difference makes the change in magnetization faster and more precise. The technology developed by Ioan-Mihai Miron offers still more benefits: less wear on the elements and the elimination of writing errors. It is called SOT-MRAM, for Spin-Orbit Torque Magnetic Random Access Memory. This technical name reflects the complexity of the effects at work in the layers of electrons of the magnetic materials exposed to the interactions of the electrical currents.

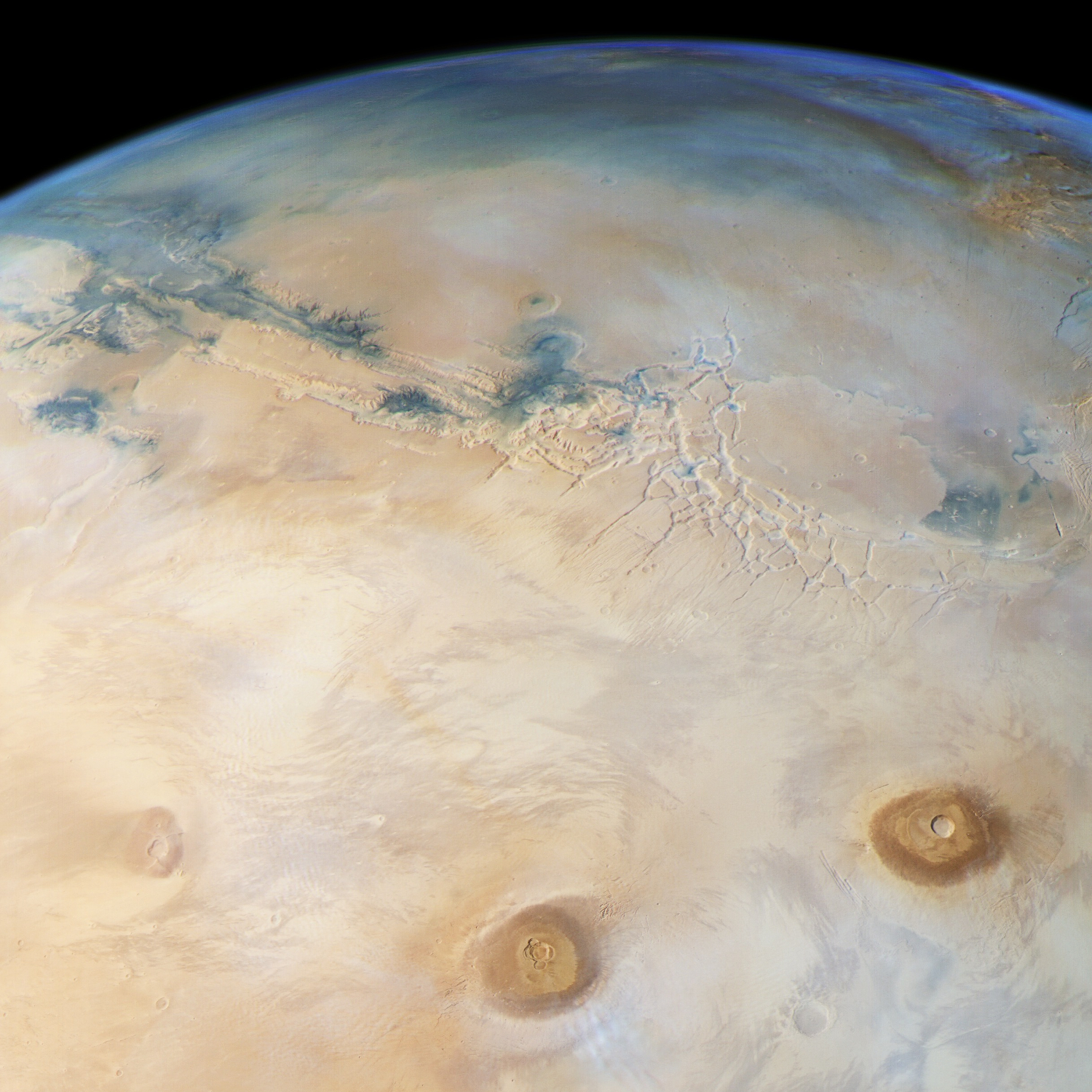

The nanostructures developed by Ioan-Mihai Miron and his team are opening new prospects for magnetic memories.

The progressive developments of magnetic memories may appear minimal. At first glance, a transition from two perpendicular currents to one linear current to save a few nanoseconds seems to be only a minor advance. However, the resulting changes in performance offer considerable opportunities for industrial actors. “SOT-MRAM has only been in existence since 2011, yet all the major microelectronics businesses already have R&D programs on this technology that is fresh out of the laboratory,” says Ioan-Mihai Miron. SOT-MRAM is perceived as the technology that is able to bring magnetic technologies to the cache memory playing field.

The winner of the 2018 IMT – Académie des Sciences 2018 Young Scientist award seeks to remain realistic regarding the industrial sector’s expectations for SOT-MRAM. “Transistor-based memories are continuing to improve at the same time and have recently made significant progress,” he notes. Not to mention that these technologies have been mature for decades, whereas SOT-MRAM has not yet passed the ten-year milestone of research and sophistication. According to Ioan-Mihai Miron, this technology should not be seen as a total break with previous technology, but as an alternative that is gradually gaining ground, albeit rapidly and with significant competitive opportunities.

But there are still steps to be made to optimize SOT-MRAM and have it integrated into our computer products. These steps may take a few years. In the meantime, Ioan-Mihai Miron is continuing his research on memory architectures, while increasingly entrusting SOT-MRAM to those who are best suited to transferring it to society. “I prefer to look elsewhere rather than working to improve this technology. What interests me is discovering new capacities for storing information, and these discoveries happen a bit by chance. I therefore want to try other things to see what happens.”

*Spintec is a mixed research unit of CNRS, CEA, Université Grenoble Alpes.

[author title=”Ioan-Mihai Miron: a young expert in memory technology” image=”https://imtech-test.imt.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/mihai.png”]

Ioan-Mihai Miron is a researcher at the Spintec laboratory in Grenoble. His major contribution involves the discovery of the reversal of magnetization caused by spin orbit coupling. This possibility provides significant potential for reducing energy consumption and increasing the reliability of MRAM, a new type of non-volatile memory that is compatible with the rapid development of the latest computing processors. This new memory should eventually come to replace SRAM memories alongside processors.

Ioan-Mihai Miron is considered a world expert, as shown by the numerous citations of his publications (over 3,000 citations in a very short period of time). In 2014 he was awarded the ERC Starting Grant. His research has also led to several patents and contributed to creating the company Antaios, which won the Grand Prix in the I-Lab innovative company creation competition in 2016. Fundraising is currently underway, demonstrating the economic and industrial impacts of the work carried out by the winner of the 2018 IMT-Académie des Sciences Young Scientist award.[/author]