Social media and crisis situation: learning how to control the situation

Attacks, riots, natural disasters… all these crises spark wide-spread action among citizens on online social media. From surges of solidarity to improvised manhunts, the best and the worst can unfurl. Hence the need to know how to manage and coordinate these movements so that they can contribute positively to crisis management. Caroline Rizza, a researcher in information and communication sciences at Télécom ParisTech, studies these unique situations and the social, legal and ethical issues they present.

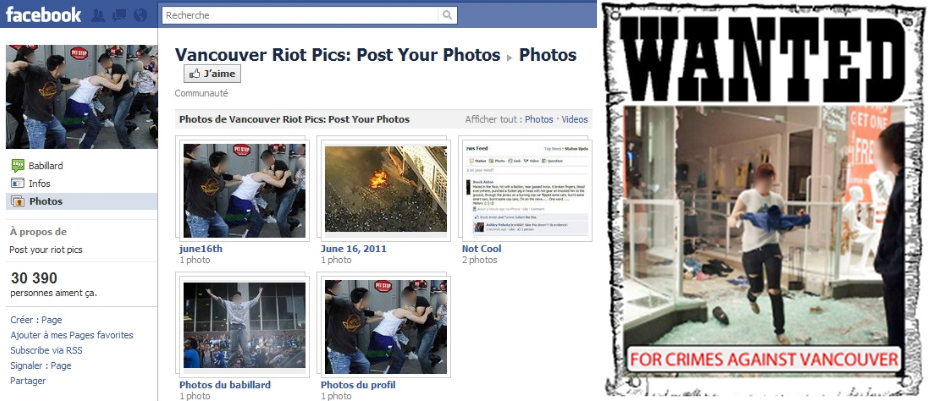

Vancouver, 2011. The defeat of the local hockey team in the Stanley Cup final provoked chaos in the city center. Hooligans and looters were filmed and photographed in the act. The day after the riots, the Vancouver police department asked citizens to send in files in order to identify the hooligans. Things soared out of control. The police were inundated with an astronomical quantity of unclear images, in which it was hard to distinguish hooligans from those seeking to contain the rioters. Citizens, feeling warranted to do so in response to the call to witness by the authorities, were quick to create Facebook pages to disclose the images and allow the identification of supposed criminals by internet users. Photographs, names and addresses spread across the internet. A veritable manhunt was organized. The families of accused minors were forced to flee their homes.

During the riots in Vancouver, citizens posted images of rioters on Facebook

and organized a veritable manhunt…

The case of the riots in Vancouver is an extreme example, but on the other side of the Atlantic, other cases of civilian mobilization have also raised new issues. In an act of solidarity during the attacks in France on 13 November 2015, Parisian residents invited citizens in danger to take refuge in their homes and shared their addresses on social media. They could have become targets for potential attacks themselves. “These practices show how civilian solidarity is manifested on social media during this kind of event, and how this solidarity can impact professional practices of crisis management and create additional difficulties” comments Caroline Rizza, a researcher in information and communication sciences at Télécom ParisTech. The MACIV project (Management of CItizens and Volunteers: social media in crisis situation), launched last February and financed by the ANR via the French General Secretariat for Defense and National Security, examines these issues. Its partners include Télécom ParisTech, IMT Mines Albi-Carmaux, LATTS, the French Directorate General for Civil Security and Crisis Management, VISOV, NDC, and the Defense and Security Zone of the Paris Prefecture of Police. At Télécom ParisTech, Caroline Rizza and her team are working on the social, ethical and legal issues posed by these unique situations.

Coordinating surges of civilian solidarity for better crisis management

“We are going to work on case studies of initiatives through crises which occur regularly or are likely to reoccur, such as train strikes or periods of snow, in order to analyze the chronological unfurling of events and the way in which online social media is mobilized,” explains the researcher. “We are also interested in the way in which information is published and spreads on online social media during serious incidents. We are going to conduct interviews with institutional operators to understand how they have been impacted internally, as well as with contributors to Wikipedia pages.” Given that the development of these pages is participatory and open, does the widely-trusted information they contain come from institutions or citizens?

For the researcher, the aim is to see the emergence of different types of organization that can later be used in crisis management. Based on the recommendations drawn from this study, the project’s objective is to integrate a management module for citizen initiatives on a platform for mediation and coordination in the event of a crisis, created by IMT Mines Albi-Carmaux, and whose development was launched in the framework of other projects such as the GéNéPI project by the ANR.

“Citizens are often mass-mobilized in a rush of solidarity during crises. Despite good intentions, the number of people taking action is often so great that they interfere with good crisis management and the phase in which the authorities take over” comments Caroline Rizza. For example, after a flood, surges of solidarity to clean the streets can in fact hinder the authorities in charge. Similarly, after the attacks in Paris on 13 November 2015, blood donor organizations started to refuse donations because they had become too numerous in too short a space of time, whereas the need for blood donations is a long term one. Hence the need to properly manage and coordinate civilian mobilization.

Data protection, fake news and unclear legal situations

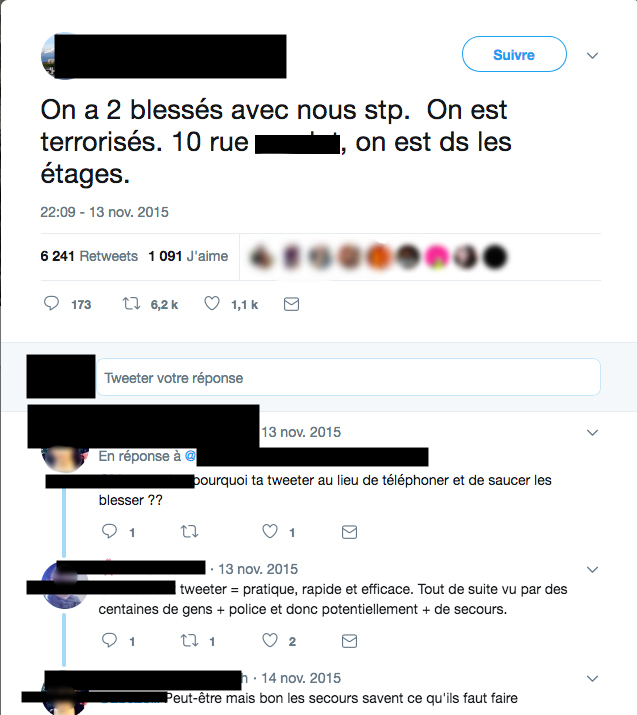

Besides the simple question of coordination, the management of mobilization among civilians and volunteers raises complex ethical and legal issues. In extreme situations, citizens are more likely to expose themselves in order to help or find an immediate solution, as shown by the “parisportesouvertes” hashtag on Twitter during the attacks of 13 November. Moreover, when the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in the south of Iceland erupted in 2010, citizens and stranded tourists shared data to organize, find alternative travel solutions or come in aid of people blocked by the eruption. The result: this data was recovered by private companies. “In the context of the transition to the GDPR, it is essential to examine the question of personal data and be able to guarantee citizens that their data will not be employed by third parties or used out of context” says Caroline Rizza.

During the attacks in Paris on 13 November 2015, some users shared their address on social media, notably through #parisportesouvertes.

But personal data is not the only thing leaked on online social media. During the attack on 14 July 2016 in Nice, false information maintained that hostages had been taken in a restaurant, when people were in fact simply taking shelter. “These rumors are not necessarily spread with bad intentions,” explains the researcher, “but it is absolutely necessary to integrate and analyze the information in order to quench rumors because they can cause even more panic.” Caroline Rizza’s hypothesis is therefore that the integration of social media in crisis management, in terms of institutional communication or transmission of information from the field, will allow rumors about an event to be quickly contained.

Lastly, what about prevention and the preparation of citizens for disasters? “Although these two phases are often left to one side by studies, there are very real challenges in ensuring that citizens participate themselves in prevention through online social media” explains Caroline Rizza. Nevertheless, the researcher stresses that the authorities must maintain an ethic of shared responsibility. They must never offload onto citizens. But what can the authorities ask citizens to do? To publish information? Help others? The legal vacuum remains…

Whatever answers the MACIV project provides to these problems, the integration of online social media in crisis management must be carefully studied. Although we cannot circumvent traditional channels of information, since not all citizens necessarily have a Twitter or Facebook account, it is no longer possible to manage crises without including the latter in the strategies. As Caroline Rizza says: “whatever happens citizens will use them in a crisis, with or without us!”