Fabrice Flipo, Institut Mines-Telecom Business School

This article was published in association with the “Does progress have a future?” series of conferences organized by the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie, from Tuesday 15 to 26 May 2018. Over a two-week period, groups of students, a panel of citizens and scientists, historians and philosophers shared their views and debated the topic.

[divider style=”dotted” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]educed food supply, loss of biodiversity, pollution, the energy crisis… Although reports pointing to the negative consequences of the current production system continue to accumulate, the economy of promises is in full swing. Growth and progress have become confused and the hope of seeing the emergence of technological solutions remains, despite all evidence to the contrary?

Ever-more capital-intensive production tools

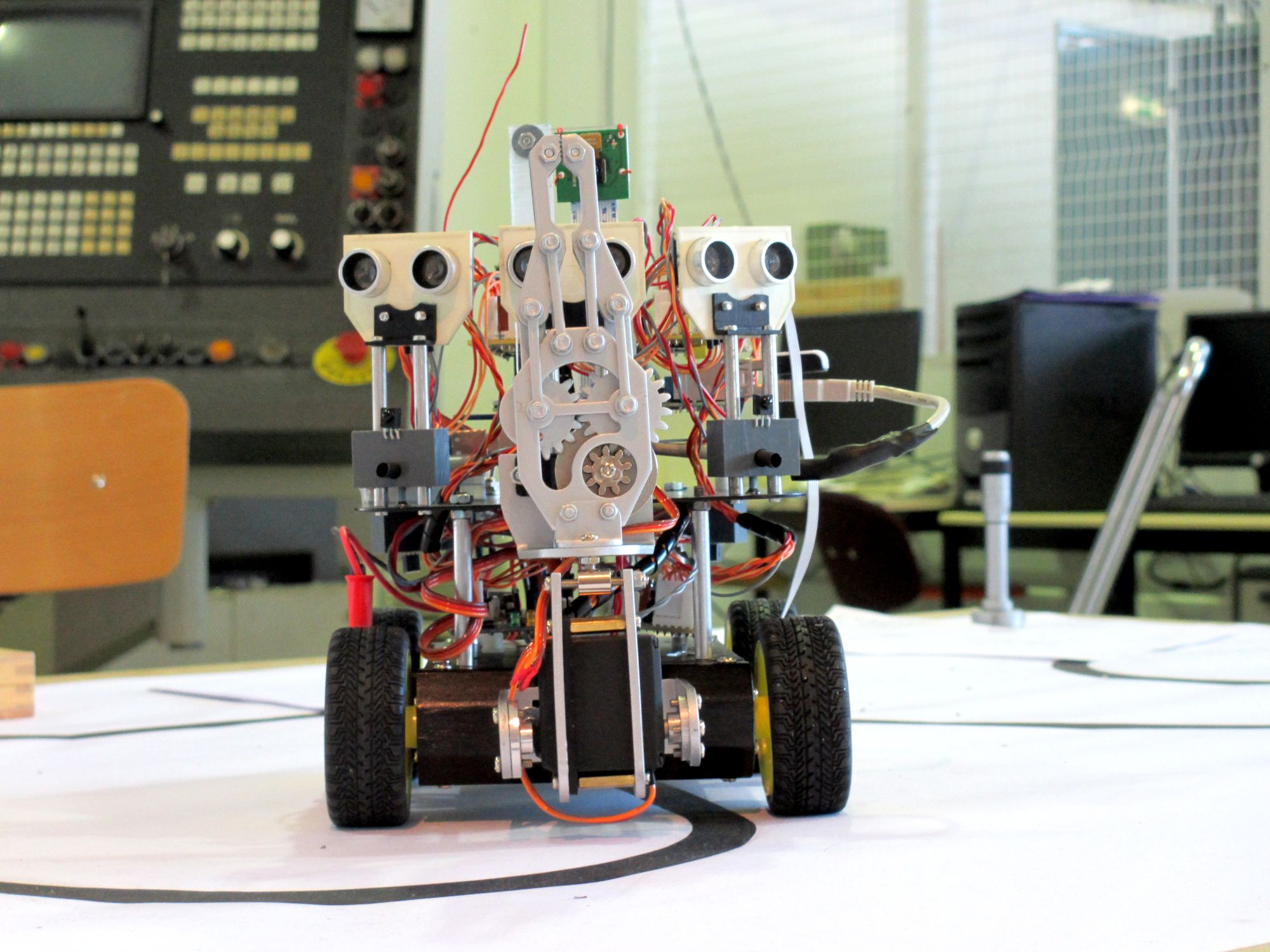

Growth has determined, and continues to determine, the meaning of progress: a “constant striving for more.” In science, sport, mobility, energy and other sectors production tools are increasingly capital-intensive: the quantity of capital necessary to put them in place continues to grow. Likewise, in biology, “modern” genetics could not exist without the machines that make it possible to analyze the genome. In astrophysics, it is impossible to observe distant stars without orbital telescopes. In the humanities, digital technology is increasingly used to study and distribute texts and make them available for the entire planet — for those who have a suitable device, that is. In sports, how can continuous record-breaking be understood without taking account of the equipment used? Round-the-world sailing is a perfect example: even the most talented sailor in the world could not win a race without a “Ferrari” of the sea.

This accumulation of capital, beyond the play of supposedly competitive markets, is central to the notion of progress that has gradually gained ground since the 19th century, a process accurately described by Marx in his works: capitalists buy, sell, and above all, accumulate.

Winner takes all

This progress is determined by rules and standards that give entrepreneurs great leeway, in both the private and public spheres (socialist economies have been described as effectively being structured by an Entrepreneurial State). This is not an outdated analysis, as can be seen both by the current success of “Communist” China and the importance of planning at all levels of “private” businesses and the economy. Although strategic management and marketing do not plan ten or twenty years ahead, they contribute to stabilizing the process toward accumulation. The model of Silicon Valley provides a striking example: billions of dollars in public funds, startups bought at 99% by major firms that continue to grow.

This is the famous “winner takes all.” The expression is often associated with digital technology, but things were no different before its development: in the automobile industry, for example, out of the hundreds of manufacturers that once existed, only ten or so are left standing.

Citizen involvement, consequences: overlooked aspects?

Against this backdrop, citizens are left with a limited role: they are seen, above all, as a malleable material, recipients of goods and services that, by definition, represent progress. In prevailing theories and decisions, citizens’ behavior is interpreted solely as a gluttonous appetite seeking only to maximize pleasure.

The example of digital technology has demonstrated this repeatedly: at the outset, it was a supply, rather than demand, market. Desire was low. It was sparked by passionate speeches by Al Gore and other public officials about “information highways” and later in Barack Obama’s speeches about smart cities. The foreseeable consequences of this digital boom, such as waste, energy consumption and dependence, were overlooked since they were at odds with the idea of progress.

Today, however, many reports have sounded the alarm for these issues: too much waste, poor waste treatment, skyrocketing energy consumption (the most alarming scenarios go so far as to predict that digital energy consumption could reach 50% of total energy consumption by 2030), dependence on rare materials etc.

These aspects were already pointed out two decades ago, by both the Council of Europe and the European Parliament. But public authorities were more concerned about falling behind than they were about the possible “technological dead end” they were headed for.

Means before the End

This concept of a “technological dead end” is mentioned in the Villani report:

“The production of digital equipment consumes a great amount of rare, critical metals that are not easily recyclable and with limited accessible reserves (15 years for Indium, the consumption of which has multiplied sevenfold in 10 years), which could lead to a technological dead end if the growing demand does do not slow down.” (p. 123)

The title of the report is worth noting: it is about providing meaning for, in other words determining how to use, AI, rather than first asking what kind of a world we would like to live in (a question of meaning) and then determining the most suitable tools to achieve this, a process whereby AI may not actually be a beneficial option.

There is little difference in “real” socialist societies. In the USSR of the 1970s a request for a telephone could take years to be fulfilled and cars were known for their poor quality. But in other fields (military, aeronautics etc.), industry was thriving. In some sectors such as healthcare, needs were sometimes better controlled in socialist societies. Life expectancy in Cuba is higher than that of United States’ citizens overall, and much higher than the life expectancy of the percentage of the American population whose skin is darker than others.

People do not fall in “love” with a growth rate

To make sure that people internalize these ideas, the race for progress relies on a vast undertaking to arouse desire, reenacting the primitive potlach (a practice in which individuals give and spend to increase prestige, according to anthropologist Marcel Mauss) on a greater scale than ever before. But it has implications that are not signs of progress: reduced food supply, ecological destruction (especially genetic) on an unprecedented scale etc.

These “negative aspects” are questioned, viewed with caution, and pushed to the background in decision-making. Meanwhile, investment is racing to keep up with dreams of grandeur and accumulation. This is illustrated by Tesla’s enormous market capitalization, despite the fact that it has never earned money and is lagging in many forecasts. Similarly, the fantastical prophecies of the controversial Ray Kurzweil, Google engineer and “futurologist,” have garnered significant media attention.

It is also significant that faced with these threats, the solution is often seen as more capitalism rather than less. The Breakthrough Institute explains that in order to protect the biosphere from growing consumption, we must tap into the earth’s resources in unprecedented quantities — and recycle, of course. “The economy of promises” is in full swing but in a single direction: toward capitalistic accumulation. Any signal to the contrary is viewed with suspicion. Messages about food supply or inequality are drowned out by the overall constant celebration of the system, as Jean Baudrillard suggested as early as the 1970s.

Refusing means regressing

Capitalism leads to a concentration of resources in an ever-smaller number of hands. As such, whatever the issue in question, it is always the same stakeholders who have the resources to present their solutions. Organizations proposing alternatives to the solutions provided by major firms are hindered by regulations that are poorly suited to their specific characteristics, and do not have the resources to send personnel to attend all the meetings that could help change this situation.

The result: views of progress that do not fall into the “always more” school of thinking are discredited as representing regress rather than progress. This is the “we aren’t going back to candles” argument heard so often despite the fact that it is unfounded since hardly anyone supports such an idea. Its only purpose is to undermine the adversary’s credibility.

Technology, a new divinity

And yet, soil insulates better than concrete, the huge quantity of medications consumed has a very limited effect relative to cost, nanotechnologies (including the star product, carbon nanotubes) and biotechnologies (two major forms of GMOs in 25 years, while gene therapy is still awaited) have not led to a revolution in terms of well-being.

“Not yet,” respond partisans of “progress,” for whom the slightest doubt is an act of sacrilege. Jacques Ellul is among those who have gone the furthest in theorizing that technology has become sacred. But partisans of progress only consent to discussing different ways of adopting and using technology, certainly not the idea of setting technology aside (or scrapping it) in favor of other possibilities and ways of seeing things.

They have 150 years of experience in “developed” countries on their side. After all, the same warnings were made in the past and “technology has managed.” Why would it be any different tomorrow? Yet certain warnings becoming realities: in her seminal work Silent Spring, published in 1962, biologist Rachel Carson announced the possible disappearance of insects and birds. 56 years later, this has almost come to pass.

Most importantly, the conditions do not allow for the emergence of real power for the (citizen)- consumer. Major firms spent 30 billion in 2017 to convince the French to use their products, according to Ademe who spent 16 million for this purpose in 2016,

“Communication with the public and professionals is crucial in order to change behavior and accelerate the energy and ecological transition in French society.”

Decisions made at the end of citizens’ conferences show, however, that when informed, citizens make very different choices than industries. Ironically, after establishing a system that incites the massive adoption of products which have become a part of everyday consumption, decision-makers now accuse the consumers when they are worried about threats. This subordinate position of the consumer, in all cases, clearly demonstrates in which direction power flows: from high to low.

Fabrice Flipo, Professor of social and political philosophy, epistemology and the history of science and technology, Institut Mines-Telecom Business School

The original version of this article (in French) was published in The Conversation.

Laurent Alleman has been an associate professor since 2004 at IMT Nord Europe (former École des Mines de Douai and IMT Lille Douai) in the

Laurent Alleman has been an associate professor since 2004 at IMT Nord Europe (former École des Mines de Douai and IMT Lille Douai) in the

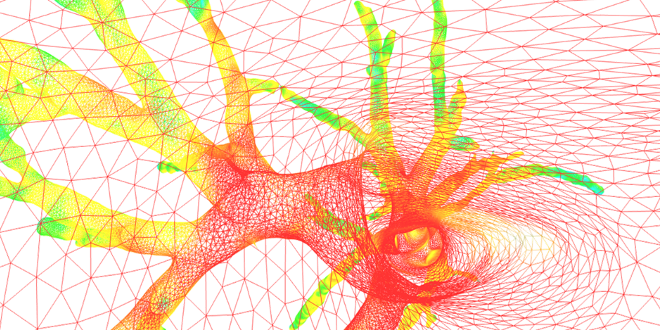

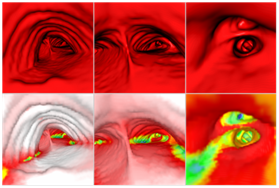

AirWays software uses a graphic grid representation of bronchial tube surfaces after analyzing clinical images and then generates 3D images to view them both “inside and outside” (above, a view of the local bronchial diameter using color coding). This technique allows doctors to plan more effectively for endoscopies and operations that were previously performed by sight.

AirWays software uses a graphic grid representation of bronchial tube surfaces after analyzing clinical images and then generates 3D images to view them both “inside and outside” (above, a view of the local bronchial diameter using color coding). This technique allows doctors to plan more effectively for endoscopies and operations that were previously performed by sight. “For now, we have limited ourselves to the diagnosis-analysis aspect, but I would also like to develop a predictive aspect,” says the researcher. This perspective is what motivated

“For now, we have limited ourselves to the diagnosis-analysis aspect, but I would also like to develop a predictive aspect,” says the researcher. This perspective is what motivated