Saving the digital remains of the Tunisian revolution

On March 11 2017, the National Archives of Tunisia received a collection of documentary resources on the Tunisian revolution which took place from December 17, 2010 to January 14, 2011. Launched by Jean-Marc Salmon, a sociologist and associate researcher at Télécom École de Management, the collection was assembled by academics and associations and ensures the protection of numerous digital resources posted on facebook. These resources are now recognized as a driving force in the uprising. Beyond serving as a means for rememberance and historiography, this initiative is representative of the challenges digital technology poses in archiving the history of contemporary societies.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]t approximately 11 am on December 17, 2010 in the city of Sidi Bouzid, in the heart of Tunisia, the young fruit vendor Mohammed Bouazizi had his goods confiscated by a police officer. For him, it was yet another example of abuse by the authoritarian regime of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who had ruled the country for over 23 years. Tired of the repression of which he and his fellow Tunisians were victims, he set himself on fire in front of the prefecture of the city later that day. Riots quickly broke out in the streets of Sidi Bouzid, filmed by inhabitants. The revolution was just getting underway, and videos taken with rioters’ smartphones would play a crucial role in its escalation and the dissemination of protests against the regime.

Though the Tunisian government blocked access to the majority of image banks and videos posted online — and proxies* were difficult to implement in order to bypass these restrictions — Facebook was wide open. The social networking site gave protestors an opportunity to alert local and foreign news channels. Facebook groups were organized in order to collect and transmit images. Protestors fought for the event to be represented in the media by providing images taken with their smartphones to television channels France 24 and Al Jazeera. Their desired goal was clearly to have a mass effect: Al Jazeera is watched by 10 to 15% of Tunisians.

“The Ben Ali government was forced to abandon its usual black-out tactic, since it was impossible to implement faced with the impact of Al Jazeera and France 24,” explains Jean-Marc Salmon, an associate researcher at Télécom École de Management and a member of IMT’s LASCO IdeaLab (See at the end of the article). For the sociologist who is specialized in this subject, “There was a connection between what was happening in the streets and online: the fight to spur on representation in through Facebook was the prolongation of the desire for recognition of the event in the streets.” It was this interconnection that prompted research as early as 2011, on the role of the internet in the Tunisian revolution — the first of its kind to use social media as an instrument for political power.

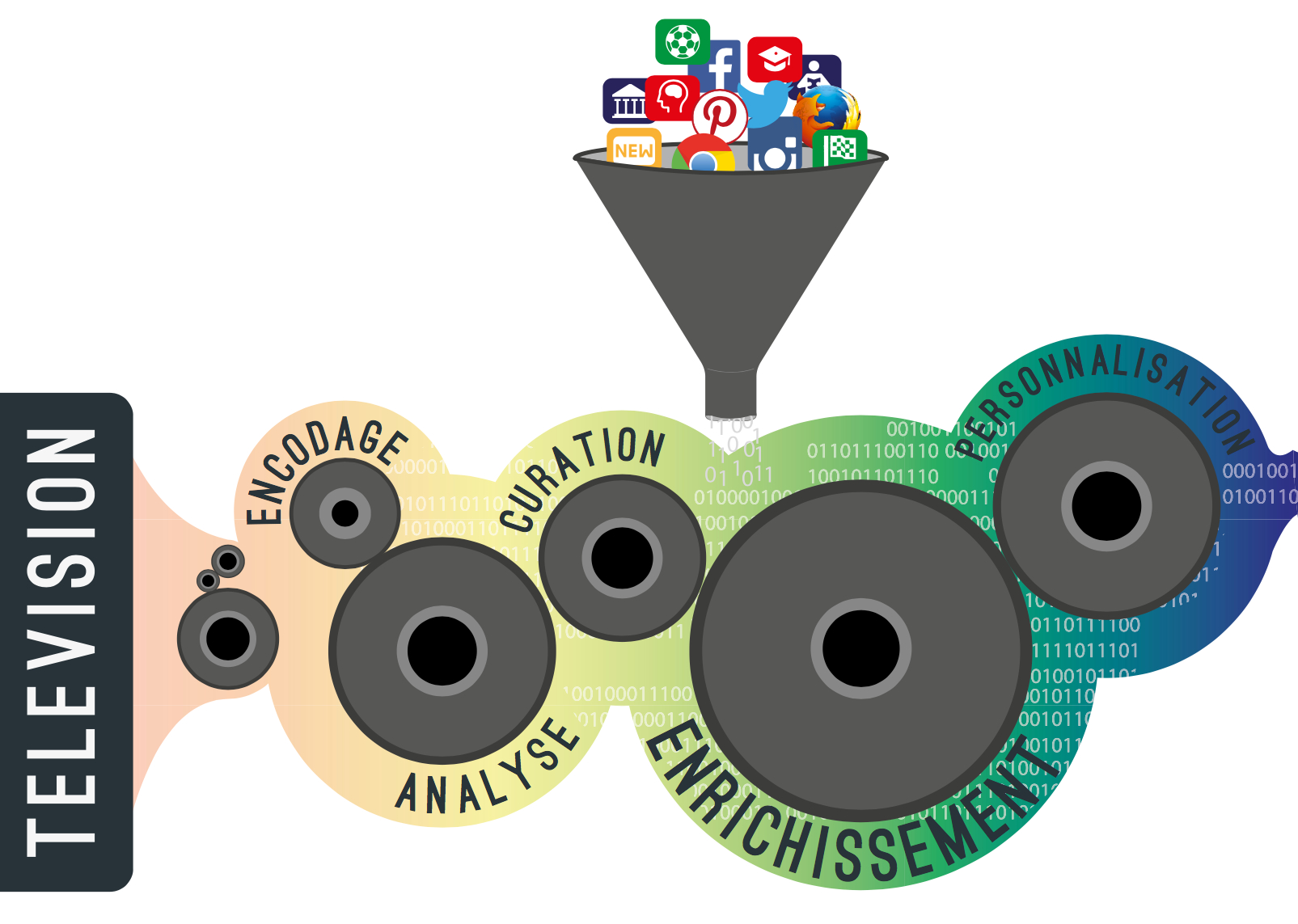

Television channels had to adapt to these new video resources which they were no longer the first to broadcast, since they had previously been posted on the social network. As of the second day of rioting, a new interview format emerged: on the set, the reporter conducted a remote interview with a notable figure (a professor, lawyer, doctor, etc.) on site in Sidi Bouzid or surrounding cities where protests were gaining ground. A photograph of the interviewee’s face was displayed on half the screen while the other half aired images from smartphones which had been retrieved from Facebook. The interviewee provided live comments to explain what was being shown.

On December 19, 2010 “Moisson Maghrébine” — Al Jazeera’s 9 pm newscast — conducted a live interview with Ali Bouazizi, a local director of the opposition party. At the same time, images of the first uprisings which had taken place the two previous nights were aired, such as this one showing the burning of a car belonging to RCD, the party of president Ben Ali. The above image is a screenshot from the program.

Popularized by media covering the Tunisian revolution, this format has now become the media standard for reporting on a number of events (natural disasters, terrorist attacks, etc.) for which journalists do not have videos filmed by their own means. For Jean-Marc Salmon, it was the “extremely modern aspect of opposition party members” which made it possible to create this new relationship between social networking sites and mass media. “What the people of Sidi Bouzid understood was that there is a digital continuum: people filmed what was happening with their telephones and immediately thought, ‘we have to put these videos on Al Jazeera.’”

Protecting the videos in order to preserve their legacy

Given the central role they played during the 29 days of the revolution, these amateur videos have significant value for current and future historians and sociologists. But, as a few years have passed since the revolution, they are no longer consulted as much as they were during the events of 2010. The people who put them online no longer see the point of leaving them there so they are disappearing. “In 2015, when I was in Tunisia to carry out my research on the revolution, I noticed that I could no longer find certain images or videos that I had previously been able to access,” explains the sociologist. “For instance, in an article on the France 24 website the text was still there but the associated video was no longer accessible, since the YouTube account used to post it online had been deleted.”

The research and archiving work was launched by Jean-Marc Salmon and carried out by the University of La Manouba under the supervision of the National Archives of Tunisia, with assistance from the Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support for Human Rights Defenders. The teams participating in this collaboration spent one year travelling throughout Tunisia in order to find the administrators of Facebook pages, amateur filmmakers, and members of the opposition party who appeared in the videos. The researchers were able to gather over a thousand videos and dozens of testimonies. This collection of documentary resources was handed over to the National Archives of Tunisia on March 17 of this year.

The process exemplifies new questions facing historians of revolutions. Up to now, their primary sources have usually consisted of leaflets published by activists, police reports or newspapers with clearly identified authors and cited sources. Information is cross-checked or analyzed in the context of its author’s viewpoint in order to express uncertainties. With videos, it is more difficult to classify information. What is its aim? In the case of the Tunisian revolution, is it an opponent of the regime trying to convey a political message, or simply a bystander filming the scene? Is the video even authentic?

To respond to these questions, historians and archivists must trace back the channels through which the videos were originally broadcast in order to find the initial rushes. Because each edited version expresses a choice. A video taken by a member of the opposition party in the street will take on different value when it is picked up by a television channel which has extracted it from Facebook and edited for the news. “It is essential that we find the original document in order to understand the battle of representation, starting with the implicit message of those who filmed the scene,” says Jean-Marc Salmon.

However, it is sometimes difficult to trace videos back to the primary resources. The sociologist admits that he has encountered anonymous users who posted videos on YouTube under pseudonyms or used false names to send videos to administrators of pages. In this case, he has had to make do with the earliest edited versions of videos.

This collection of documentary resources should, however, facilitate further efforts to find and question some of the people who made the videos: “The archives will be open to universities so that historians may consult them,” says Jean-Marc Salmon. The research community working on this subject should gradually increase our knowledge about the recovered documents.

Another cause for optimism is the fact that the individuals questioned by researchers while establishing the collection were quite enthusiastic about the idea of contributing to furthering knowledge about the Tunisian revolution. “People are interested in archiving because they feel that they have taken part in something historic, and they don’t want it to be forgotten,” notes Jean-Marc Salmon.

The future use of this collection will undoubtedly be scrutinized by researchers, as it represents a first in the archiving of natively digital documents. The Télécom École de Management researcher also views it as an experimental laboratory: “Since practically no written documents were produced during the twenty-nine days of the Tunisian Revolution, these archives bring us face-to-face with the reality of our society in 30 or 40 years, when the only remnants of our history will be digital.”

*Proxies are staging servers used to access a network which is normally inaccessible.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

LASCO, an idea laboratory for examining how meaning emerges in the digital era

Jean-Marc Salmon carried out his work on the Tunisian revolution with IMT’s social sciences innovation laboratory (LASCO IdeaLab), run by Pierre-Antoine Chardel, a researcher at Télécom École de Management. This laboratory serves as an original platform for collaborations between the social sciences research community, and the sectors of digital technology and industrial innovation. Its primary scientific mission is to analyze the conditions under which meaning emerges at a time when subjectivities, interpersonal relationships, organizations and political spaces are subject to significant shifts, in particular with the expansion of digital technology and with the globalization of certain economic models. LASCO brings together researchers from various institutions such as the universities of Paris Diderot, Paris Descartes, Picardie Jules Verne, the Sorbonne, HEC, ENS Lyon and foreign universities including Laval and Vancouver (Canada), as well as Villanova (USA).

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

This operates as a digital platform and aims to replace the existing tools used by orthoptists, which are not very ergonomic. This technology consists solely of a computer, a pair of 3D glasses, and a video projector. It makes the technology more widely available by reducing the duration of tests. The glasses are made with shutter lenses, allowing the doctor to block each eye in synchronization with the material being projected. This othoptic tool is used to evaluate the different degrees of binocular vision. It aims to help adolescents who have difficulties with fixation or concentration.

This operates as a digital platform and aims to replace the existing tools used by orthoptists, which are not very ergonomic. This technology consists solely of a computer, a pair of 3D glasses, and a video projector. It makes the technology more widely available by reducing the duration of tests. The glasses are made with shutter lenses, allowing the doctor to block each eye in synchronization with the material being projected. This othoptic tool is used to evaluate the different degrees of binocular vision. It aims to help adolescents who have difficulties with fixation or concentration. The researchers have used liquid crystals for many industrial purposes (protection goggles, spectral filters, etc.). In fact, liquid crystals will soon be part of our immediate surroundings without us even knowing. They are used in flat screens, 3D and augmented reality goggles, or as a camouflage technique (Smart Skin). To create these possibilities, Arago’s manufacturing and testing facilities are unique in France (including over 150m² of cleanrooms).

The researchers have used liquid crystals for many industrial purposes (protection goggles, spectral filters, etc.). In fact, liquid crystals will soon be part of our immediate surroundings without us even knowing. They are used in flat screens, 3D and augmented reality goggles, or as a camouflage technique (Smart Skin). To create these possibilities, Arago’s manufacturing and testing facilities are unique in France (including over 150m² of cleanrooms).